RANGE continues to report on PFAS in West Plains groundwater. If you have information you would like to share about this topic, we’d love to hear from you at team@rangemedia.co.

In the years leading up to 2017, people living on the West Plains started noticing the strange illnesses.

In 2014, Larry Zambryski, a Spokane X-ray technician who decorated his West Plains house with homemade steampunk lamps, began suffering from unexplained thyroid problems that doctors couldn’t initially explain, and that made him so sick he couldn’t work for eight months. He and his wife Marcie had to get rid of their goats and alpacas because he lacked the energy to care for them.

Larry underwent treatment and got better, but in 2021, he died over the course of 67 days after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. About a year later, his mother-in-law, Shirlie Morgan, who lived in that home with the Zambryskis, died of a rare form of breast cancer. During this timeframe, two of the Zambryskis’ five boxers died from cancer as well.

Marcie Zambryski, who teaches elementary school in Spokane, didn’t know until months after her husband died that her well was contaminated with a special class of toxic chemicals. The compounds, known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are known to cause cancer and a host of other diseases – including liver problems – in humans and animals. Some environmentalists refer to them as “forever chemicals” because they are notoriously hard to remove from environments and only break down over thousands of years.

Marcie no longer feels comfortable canning the vegetables she grew in garden boxes Larry had built for her and giving them away. PFAS can make its way into produce grown using contaminated water.

“One year we had, I don't know, 50 tomato plants,” she told RANGE. “There's a great salsa recipe from our tomatoes.” She would give jars of it away to friends and family. “It was very yummy, and it was all toxic.”

In 2013, just up Euclid Road, not too far from the Zambryskis, Jim Dalton learned his left kidney was shot through with cancer. The operation to remove it left a foot-long scar running up his abdomen.

“It was about the size of a grapefruit, the tumor,” Dalton told RANGE. He was perplexed. “Why am I getting cancer of the kidney? Why?” His brother George didn’t have it, Dalton remembers thinking, “my other brothers don't have it, no one in my family has it.”

Dalton also has PFAS in his well. The cancer persisted; in March of this year, doctors used a rod and a camera to remove parts of Dalton’s right kidney, leaving his left side covered in pink, dime-sized scars. He seems better now, without those parts.

Shelly Sumner, who lives among the still ponderosa stands of Deep Creek, initially thought liver problems among the Wheaten terriers she breeds was a strange coincidence. One dog’s annual urine test came back with “some funky liver function values,” Sumner told RANGE. Then a second dog yielded similar results.

Around this time, word began to circulate among neighbors and even in newspapers about poison in the water. The dogs kept falling ill, and Sumner realized she needed to know what was going on.

“By the time a third dog had that, I thought, ‘I'm gonna have the well tested,’” Sumner said.

She paid Anatek Labs $400 to analyze her drinking water, and their technicians found PFAS. Since 2017 three of her dogs have died from cancer.

No one knows the extent of the contamination in the West Plains groundwater, and it’s difficult to tie any one illness to pollution. But the danger is frightening enough that Airway Heights has bought water from the City of Spokane since PFAS was discovered in that city’s municipal well in 2017.

Airway Heights is only one of several communities on the West Plains, and many people in more rural areas get their water directly from private wells, which are only lightly regulated, and not subject to routine testing. Property owners have to pay for it themselves, or, if they fall inside a specific line, the Air Force will test for them, giving them bottled water or filters for their wells.

The Air Force offers these resources because, until March, the blame for the PFAS contamination had fallen on Fairchild Air Force Base (FAFB): for decades, the base – like military installations and airports across the country – was required to use a foam material containing PFAS in firefighting drills. The chemicals ran off hard surfaces and seeped into the honeycomb of underground water bodies called aquifers from which the community drew its drinking water.

But now, another polluter has stepped into the West Plains contamination saga. According to an August 17 letter from the Washington Department of Ecology (DoE), the Spokane International Airport (SIA) is also responsible for putting PFAS into the groundwater using the same firefighting foam.

What’s more, for the last six years, SIA knew about its own pollution – it had hired contractors to sample the aquifer under the airport – but kept its well test results secret from the public. Ecology only learned of it because a concerned citizen dug up SIA’s well test results through a public record request and gave them to the agency late last winter or early in the spring.

If the person, who RANGE spoke with, had not given those records to the Washington Department of Ecology, the Spokane International Airport’s poison problem may still be a secret.

Clean up and liability

After the whistleblower gave those documents to Ecology, Stephanie May, a spokesperson for the agency based in Spokane, told RANGE that SIA “is now a liable party under the state’s Model Toxics Control Act” (MTCA) and must make a plan to clean up the site.

(RANGE granted the whistleblower anonymity because they fear reprisals from neighbors and officials, and because the documents they provided were independently verified by Ecology.)

In its August letter, Ecology told SIA that the agency can issue an administrative order imposing a penalty of up to a $25,000 a day if the airport does not clean up the site under MTCA rules.

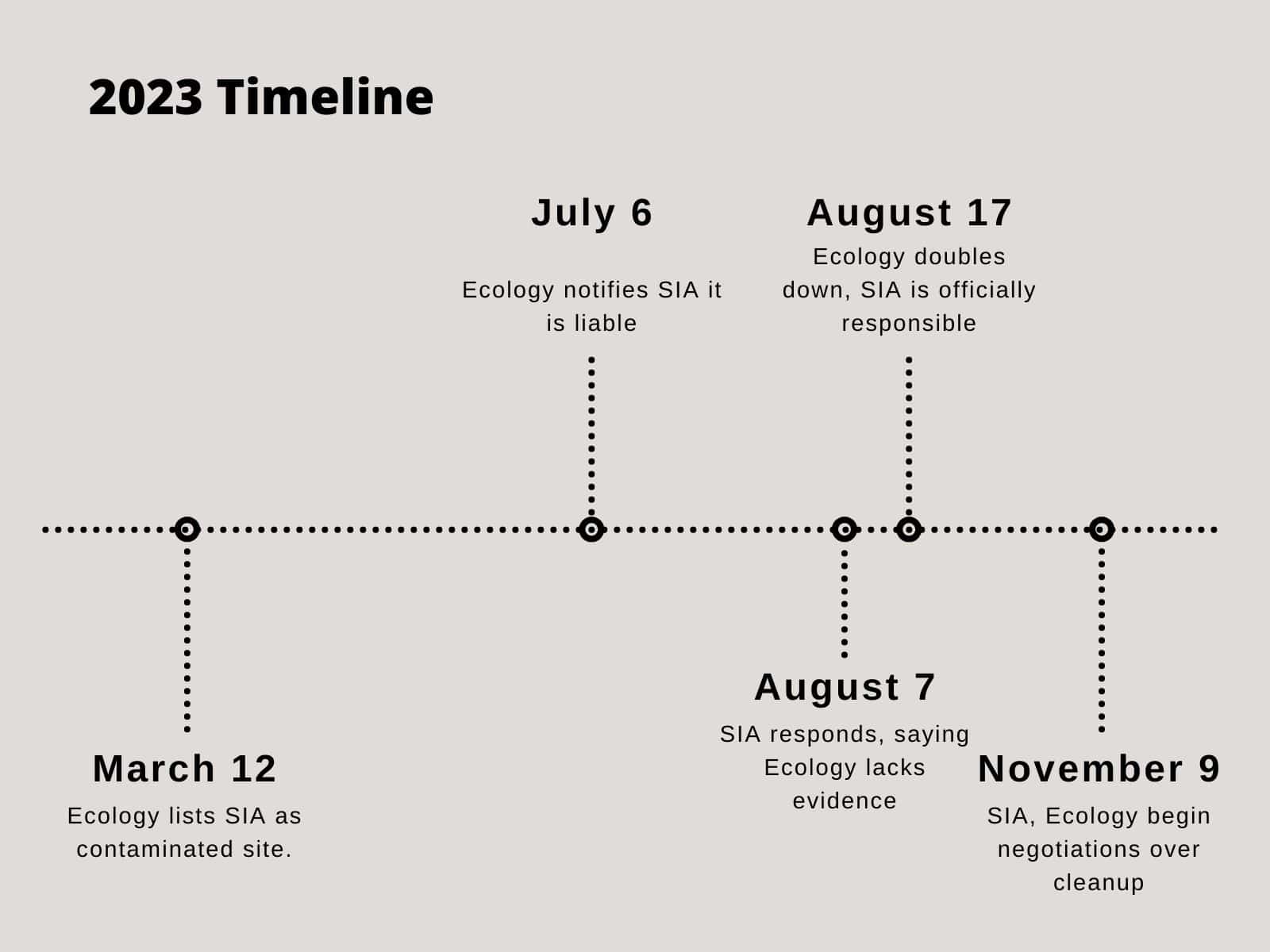

An attorney representing SIA asserted in an August 7 letter to Ecology that it had offered insufficient evidence to declare the airport liable, but SIA and the agency are now in talks to craft a cleanup plan under the MTCA. The state’s MTCA program is similar to EPA’s Superfund in that the polluter is required to pay for the cleanup.

Ecology outlined a plan for clean up and remediation in an Agreed Order and asked SIA to provide initial responses and suggested revisions by November 8. SIA missed that deadline and requested a 60-day extension the following day “to obtain technical and expert review and analyses of your proposed scope of work.” Ecology granted an extension instead to December 4. Nick Acklam, who manages Ecology’s Toxic Cleanup Program in the Spokane area, said Thursday that Ecology had received SIA’s comments and is reviewing them.

Airport CEO Larry Krauter and spokesman Todd Woodard did not respond to emails from RANGE requesting comment on this story.

The airport’s liability, according to Ecology, is based on the documents the concerned citizen obtained and gave to the agency. Those documents show SIA has known for six years that some kinds of PFAS existed at levels dangerous to human health in test wells near the tarmac. Despite knowing these toxic risks, SIA didn’t disclose the results to either environmental regulators or the general public.

In 2017, in one test well near a taxiway for planes, investigators with the environmental consulting firm AECOM detected PFAS levels at 350 parts per trillion (ppt), almost 90 times the four-ppt level the EPA suggested in 2022 as a minimum reporting level. Four parts per trillion is the smallest amount detectable by current technology in water and is equivalent to 0.4 cents out of $1 billion. The previous limit, established by Ecology, was 70 ppt, but there is no consensus on what PFAS level, if any, is safe for human consumption.

A recent Seattle Times investigation of PFAS on the West Plains tells the story of David Snipes, a rancher who lives near the airport. According to the Times, after FAFB had discovered PFAS in the groundwater, Snipes emailed Krauter, asking whether the airport may also have inadvertently released the chemicals. In a May 19, 2017 reply to Snipes, according to the Times, Krauter assured Snipes that “we do not have any kind of situation here … Accordingly, we do not have cause to be interested in testing groundwater.”

Just four days later, the airport began its initial testing.

After those 2017 tests were done, wells with even worse contamination were discovered. In subsequent testing performed by investigators with Spokane Environmental Services in 2019, a different well yielded one kind of PFAS at 5,200 ppt, or 1,300 times the four-ppt level, for one kind of PFAS.

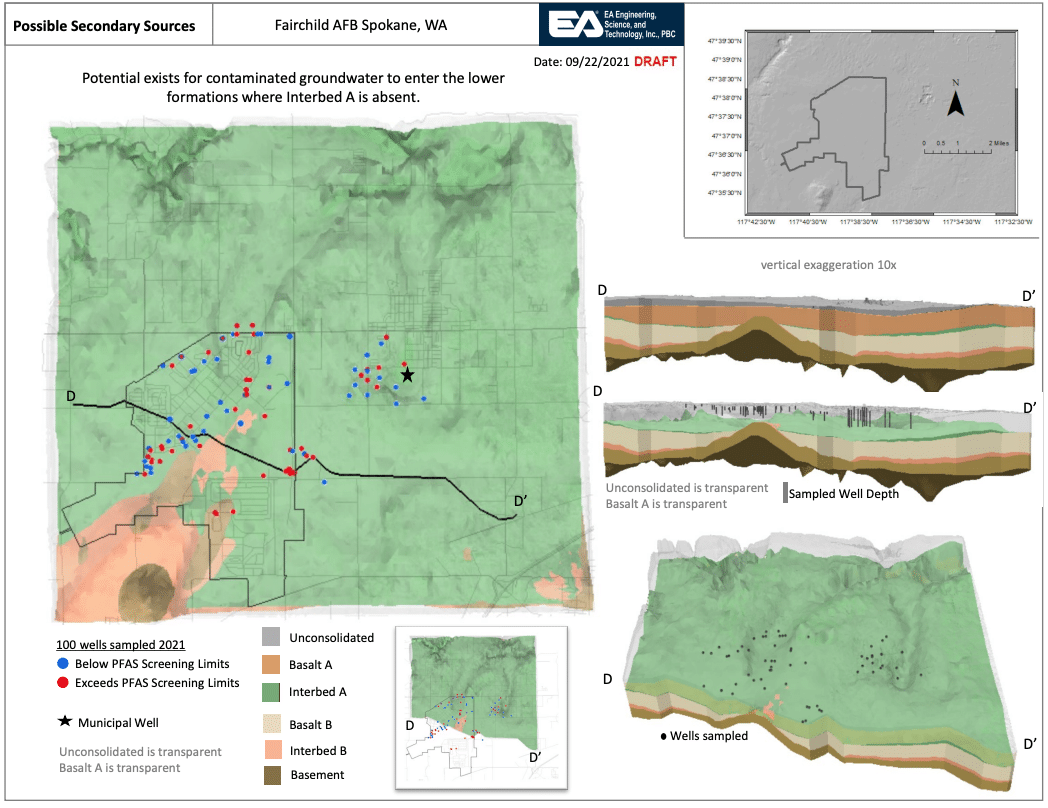

The test wells are hydrologically connected via aquifers to private wells used for drinking water on the West Plains. The aquifer system is complex, so it’s unclear whether similar levels would appear in drinking water wells miles away. But many West Plains well owners have seen their well tests come up positive for PFAS. There is no central resource that comprehensively shows where in the aquifers PFAS lurks.

All of these groundwater sources flow, eventually, into the Spokane River.

Hundreds of wells

Several interconnected aquifers lie beneath the West Plains between the two airports and the Spokane River. The water in these aquifers was once very clean because it was naturally filtered through sediments accumulated during the massive Missoula Floods that occurred in this region between 15,000 and 12,000 years ago.

(For clarity: the West Plains aquifers are distinct from the Rathdrum Prairie aquifer, the largest water source in the area which serves Spokane, Spokane Valley, and parts of the Idaho Panhandle, so the Airport and Fairchild contaminations have not been found in those communities.)

Before PFAS chemicals were identified as being harmful to human health, people moving into the West Plains drilled wells into it. Many of those wells are private and, because the extent of the aquifers is unknown, realtors and homeowners selling those properties can be unaware of the potential threat and so cannot inform any buyer about the contamination.

Although airport firefighters have sprayed the firefighting compound, called aqueous film forming foam (AFFF), on the taxiways during drills for decades, pushing PFAS into the aquifer, before 2017, wells in this area had only been tested for bacteria and other contaminants. Because the dangers of PFAS weren’t widely understood, no one suspected there were cancer-causing poisons in the drinking water, and so no one tested for them.

The West Plains is seen by some as a prime area for future development. On places along and near Euclid Road, several recent industrial operations are either already functioning or planned, including one operating rock quarry and another one proposed on 167 acres just north of Airway Heights.

About 1,400 private wells have been drilled in the West Plains PFAS risk area, said John Hancock, a water quality activist who lives on the West Plains. The Air Force has tested about 400 of them inside the FAFB study area. The study area is currently bounded by roads rather than the edges of the aquifer, and some wells outside it have tested positive for PFAS.

Inside the risk area boundary, FAFB has installed well filters on about 100 of these wells, he told RANGE. Thousands of other wells are drilled into these same aquifers outside the risk area. Many are decommissioned, are in areas served by municipal water systems or are thought to be upstream of the pollution in the aquifer currents, which generally flow northeast.

But the airport is only in the beginning stages of its cleanup process and does not have filtering and bottled water programs akin to FAFB’s in place. Community members have accused the airport of covering up the contamination because it owns — and is actively developing — 6,000 acres of land on the West Plains. Poison water could affect the profitability of that land, they contend.

“They did some of the right thing,” Hancock said of SIA’s testing, but he went on to emphasize that it should have informed the public even before it was required to do so. “They just kept it secret instead of telling the neighbors because it would be a threat to property values around the airport expansion.”

SIA is currently building a 144,000-square-foot expansion of its C terminal. It’s a $150 million project that will add three gates and six ticket counters, making it the biggest expansion of the airport in history. Airport CEO Krauter told the Spokesman-Review last year the expansion will help to meet development needs in eastern Washington and characterized it as essential to the future of the local economy.

“We must create a world-class experience that welcomes passengers to” Spokane, Krauter told the Spokesman.

Discovering toxic chemicals there might hamper those development efforts, and SIA’s critics say that’s why the airport never told the public its role in the contamination. RANGE asked Krauter via email why the airport didn’t notify the public of the contamination when it learned of it, but he did not respond.

Hancock, who is also the former executive director of the Spokane Symphony, recently founded the West Plains Water Coalition, a group that wants to independently map PFAS more completely across the West Plains aquifers.

One of his goals is to create a user-friendly database that would allow thousands of private well owners to know whether their drinking water is contaminated or at risk of contamination. Private well owners have more at stake than municipal water users because they do not benefit from Spokane’s water provisions to Airway Heights. Some of the well owners may not be able to afford to test and filter their own wells.

The Air Force now delivers between nine and 15 three-and-a-half-gallon water bottles to Marcie Zambryski’s home on a biweekly basis, but she has not signed a contract for a well filter because it would require her, among other restrictions, not to build any habitations for people on her property. In an interview with RANGE, Zambryski said she was outraged that polluters can be so flippant toward people they harm.

“It just blows my mind to think that our society hasn't moved forward enough – our government hasn't moved forward enough – to protect the people that they serve,” she said.

Aquifer contamination is not only a problem for private well owners – it also hampers development in broader ways. Former Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart, who is now the executive director of the Spokane Low-Income Housing Consortium (SLIHC), said PFAS is causing ripples in the housing market from the West Plains all the way to the Idaho border. He said SLIHC recently wanted to purchase a plot of land to build enough housing for 100 people, but he had to cancel the deal because the water supply was unsafe. Because it’s so hard to find safe water in the West Plains, Stuckart said, the merging cities of eastern Washington are growing in a lopsided way, which leaves Spokane retreating eastward.

“You've seen a massive growth over in the Rathdrum Prairie, and Post Falls and Idaho are all growing at five-plus percentage points,” Stuckart said. “Then the closer you get to Spokane, that growth percentage just goes down. And so you have the whole population center being pulled over, pulled away, from the urban core.”

Required to report

At the time the airport found these chemicals in its wells, it was not required to report its spills because Washington state did not classify PFAS as hazardous chemicals.

Woodard, the airport spokesman, told the Seattle Times in a statement that SIA was not required to report its test results to Ecology at the time they were measured because PFAS was not categorized as hazardous.

“It’s important to note the evolution of PFAS understanding, awareness and reporting standards nationally and statewide during this era,” Woodard wrote to the Times. “Specifically in 2017, the Department of Ecology had not yet formulated mandatory reporting requirements for PFAS. There was no requirement to report in 2017 or 2019.”

But in 2021, the state reclassified PFAS as hazardous and began requiring disclosure, even for releases that happened in the past. “Any person or entity with known concentrations of PFAS should have reported it” to Ecology, said Acklam.

Still, leaders at Spokane International Airport did not tell the public.

It wasn’t until that private citizen collected the records and submitted them to Ecology that the disclosure process began.

Ecology added the airport to its list of contaminated sites on March 12.

Relying on holes in environmental regulation to justify withholding information that affects public echoes throughout the history of PFAS, and has parallels to other large-scale corporate coverups, like those of the tobacco industry. According to corporate lawyer Robert Bilott’s book Exposure, companies that used PFAS in the manufacturing of their most popular products began seeing troubling health data in their research as early as the 1950s, but chose not to disclose it to the public because the EPA did not classify PFAS as hazardous at the time.

This creates a catch-22. The vast majority of research into chemicals is done by the private companies themselves, far more than the EPA and other agencies can do, but manufacturers have a financial interest in obscuring bad news. If PFAS is poison, it wouldn’t sell as well or in as many varied forms. And if the companies don’t report, it’s less likely the EPA will understand the risks enough to classify, meaning the companies aren’t required to report.

This loop continued with PFAS until Bilott chose to represent a West Virginia farmer in a lawsuit filed in 2001 against DuPont, alleging the company poisoned his cattle and hid the evidence. By 2017, in a series of settlements, Bilott had won more than $700 million in damages and more than $250 million in medical monitoring from DuPont on behalf of 70,000 residents of Ohio and West Virginia. He won a Right Livelihood award, known as “the alternative Nobel Prize,” for this work.

Terminal expansion

Although we don’t always think of airports through the same economic lens as we think about big manufacturers, they are massively important to regional economies, and many of the same financial incentives for hiding PFAS from public disclosure exist at SIA as they did at DuPont and 3M.

Like any airport serving a mid-sized American city, Spokane International has a direct interest in economic development on the West Plains. Part of its purpose is to help Spokane grow, and building a thriving ecosystem of commerce west of the city is central to that goal.

The airport is jointly owned by the city of Spokane and Spokane County. It is organized under SIA’s governing board of directors, which is chaired by Nancy Vorhees, the former chief administrative officer of the Inland Northwest Health Association. The board also sets policy for Felts Field Airport and essentially functions as a port authority for the airport’s Foreign Trade Zone, according to an SIA report to the Washington State Transportation Commission. That report, citing the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), said the airport has a $1.8 billion impact on the surrounding community.

According to the board’s website, the airport derives operating revenue from its properties. The site points out that the airport doesn’t benefit from tax revenue.

The rest of the airport board consists of members appointed by the City of Spokane and Spokane County, including elected officials like County Commissioner Al French and the Spokane City Council President, C-suite officers of local construction companies and the president of the Spokane Teachers Credit Union. Vorhees’s vice chair on the board is Jennifer West, the founder of JPW Communications, a Carlsbad, Calif. consulting firm. The secretary is County Commissioner French. The four remaining members include two developers, former Spokane City Council Member Lori Kinnear and a credit union official.

The board is not an oversight body.

Ben Stuckart, who served on the board of directors from 2013 to 2019, said it primarily functions as something of a legislative branch, making rules and approving contracts. He remembers the board being laser-focused on starting a construction for its terminal expansion between 2017 and 2019 – the same time period during which SIA discovered PFAS in its test wells.

During those years, Stuckart said, “I probably spent 60 hours outside of board meetings just at meetings about the expansion project.”

Because a huge part of an airport’s public service mission is to support the economic development of the surrounding community, Stuckart said, it makes sense for SIA’s governing board to train its eyes on building out the surrounding economy.

“That's normal,” Stuckart said. “It's your facility that sees the public, and you're constantly figuring out how to better serve them.”

Acklam and Jeremy Schmidt, Ecology’s manager of the airport cleanup site, recently met with airport representatives to discuss the beginning stages of the cleanup. Reporters were not allowed in that meeting because Ecology wanted airport officials to feel they could “speak freely,” Acklam said. Airport CEO Krauter; environmental attorney for SIA Jeffrey Longsworth, who represents SIA; and SIA general counsel Brian Werst all attended the meeting, Acklam said. He characterized the meeting as productive and said it seemed the airport wants to cooperate with the cleanup process going forward.

“The messaging we got today is they want this to be a collaborative process,” Acklam said the day of the meeting. “We’re working together and using our time and resources toward the cleanup rather than basically fighting it out.”

It’s possible, Acklam said, that other liable parties could be identified as part of the process and would negotiate their share of the cleanup burden with SIA. Ecology would have no role in those negotiations, Acklam said.

Asked about the meeting over the phone that same day, Longsworth declined to comment on this story.

Before cooperation, tense exchanges

Acklam initially informed the airport of Ecology’s determination that it had poisoned the groundwater in a July 6 letter first reported by Timothy Connor, a Spokane journalist, in his Substack newsletter, Rhubarb Salon. In the letter, Acklam told SIA it would be required to establish a cleanup plan.

Though Ecology can issue fines to SIA, spokesperson Stephanie May, told RANGE in an email the agency prefers to work toward cleaning up the site rather than punishing the airport.

“We would like to establish a collaborative relationship with Spokane International Airport to solve a complicated environmental issue that effects the local communities drinking water,” May wrote. “We believe that is more important than issuing a penalty at this time.

Longsworth replied to Acklam August 7. He said Ecology had no evidence to show the airport had polluted the aquifer. Longsworth asked the agency to “retract” the initial letter and delist the airport from its “list of confirmed and suspected contaminated sites. “

But Ecology had used SIA’s own well test documents to conclude the airport is liable for PFAS in the aquifers.

Acklam followed up August 17 with the second and final letter, saying, “Groundwater monitoring conducted by SIA confirms the presence of contaminants that are associated with the previously released hazardous substances and these contaminants pose a threat to human health and/or the environment.”

The start of a long process

PFAS is called a forever chemical because it degrades extremely slowly in natural systems — whether that’s in the environment, or the human body — and is therefore more difficult than most chemicals to remove from an environment once it is there.

The process for clean-up is long as well. Ecology’s designation of SIA as a contaminated site requires the airport to establish a cleanup plan under the MTCA, a lengthy and arduous process that begins by determining the scope of the pollution. MTCA requires the airport to give the public multiple opportunities to give feedback.

Acklam said this particular project will be difficult not only because of PFAS’s stubborn attribute of remaining in a place, but also because the geological complexity of the aquifer system makes it hard to determine the extent of the contamination. “You can’t tell, just by looking at the geography of the plains, where and how water flows under the ground,” John Hancock told us. While methods for cleaning the water in the aquifer still have to be sorted out, Acklam said, SIA must make sure people who draw drinking water from the aquifer have access to clean water.

Researchers and activists have for years tried to get state and local agencies to study the extent of the pollution by testing privately owned wells far past the boundaries of the established FAFB study area. But some local agencies have been hesitant to accept funding for such a project, according to interviews RANGE has conducted with three people involved in getting funding.

This year, EWU hydrogeologist Chad Pritchard, secured a $450,000 grant from Ecology to do that study, which will be administered by the city of Medical Lake. The hope is that, when the study is complete, private well owners will be able to consult information telling them whether they are at risk of having a contaminated well.

This effort will take years.

In the meantime, Hancock of the West Plains Water Coalition and a crew of West Plains activists are organizing informational community meetings and working with policymakers, geologists and public health officials to create a framework for folks to live with PFAS in their wells. They are also producing a documentary on West Plains PFAS in collaboration with the local filmmaker Don Hamilton. The coalition will host a meeting tonight at 7 pm at the HUB in Airway Heights and another next Thursday at the same time.

This is the kind of political work Hancock said needs to be done to solve problems caused by PFAS.

“Science and medicine have known about PFAS for a long, long time,” he said. “So if it was just science and medicine, this would have been solved a long time ago. It's politics and government that have kept the lid on this story. And that's where the solution has to come from. It's government politics. Because scientists can't clean it up.”

https://rangemedia.co/what-are-forever-chemicals-why-in-water-airway-heights-pfas/