For weeks, my family and I hunted for our white whale: a three-bedroom apartment in Spokane, Washington. After weeks and weeks of refreshing Zillow, Craigslist and Realtor.com every morning, I finally found it — a listing for a three-bedroom apartment posted just minutes earlier. When I called to inquire about it, the receptionist was shocked that someone had already found the listing. Our quest had at last come to an end.

Our search for an apartment was nearly six years ago now, but not much has changed. Spokane’s housing crisis has only gotten worse, and three-bedroom rentals are still uncommon. A quick search of Zillow shows that currently, just 23% of the available homes and apartments have three or more bedrooms.

There are plenty of studios, one-bedrooms and two-bedrooms available, but for families wanting three bedrooms, finding a place to live is incredibly stressful. It’s also the result of a seemingly insignificant piece of state code that changed how buildings could be developed in Washington and de-incentivized the construction of apartments that could fit a family.

How building up instead of out can help

In 2020, 69% of our city’s housing stock consisted of single-family detached houses, but there are times in life when we want to have the choice to live in an apartment or townhome or duplex: recent grads, single folks, new-to-town-house-hunting families, older couples, people who just aren’t interested in home and yard maintenance, people interested in the night life and others might want something other than a single-family house, or might want to live in the heart of the city. And for those interested in public safety, downtowns are safer and more vibrant when more people live, work and frequent them.

Building the denser housing is fiscally responsible: every mile of water pipe, sewage pipe, and street built costs the city tax dollars to maintain. The city saves money when that mile serves 1,000 residents rather than 100 you’d get in Spokane’s outlying areas. (There’s no moral superiority here; I live in one of those outlying areas.)

Denser housing is also more climate friendly: it allows for fewer car trips (why drive to the park when you can walk?) and requires less energy to heat. It also prevents our area’s green space and farmland from being overrun with sprawling housing developments.

If all these benefits exist, why is Spokane still missing so much middle and high density housing? One problem is building code. If we want developers to build these types of housing, the building code must allow them to be built profitably.

While the city has removed parking minimum mandates and allowed multi-family homes to be built on lots previously reserved for single-family homes — hugely important steps towards incentivizing building of denser housing — there’s more to do.

Other parts of building code, like seemingly-boring stairway codes, also make building housing difficult. But soon, a bill in the state legislature could help.

Double the stairs, half the benefits (or, artificial limitations to building up)

To build a residential building with four or more floors (or a mixed-use building with retail on the ground floor and three or more floors of housing above), Spokane’s code currently dictates that each dwelling unit must have access to two stairways to evacuate. These requirements came about with building codes created when large urban fires, like the one that destroyed much of downtown Spokane in 1889, were recent memories.

We’ll get into fire safety in a second, but first I’ll explain how two stairways impact housing.

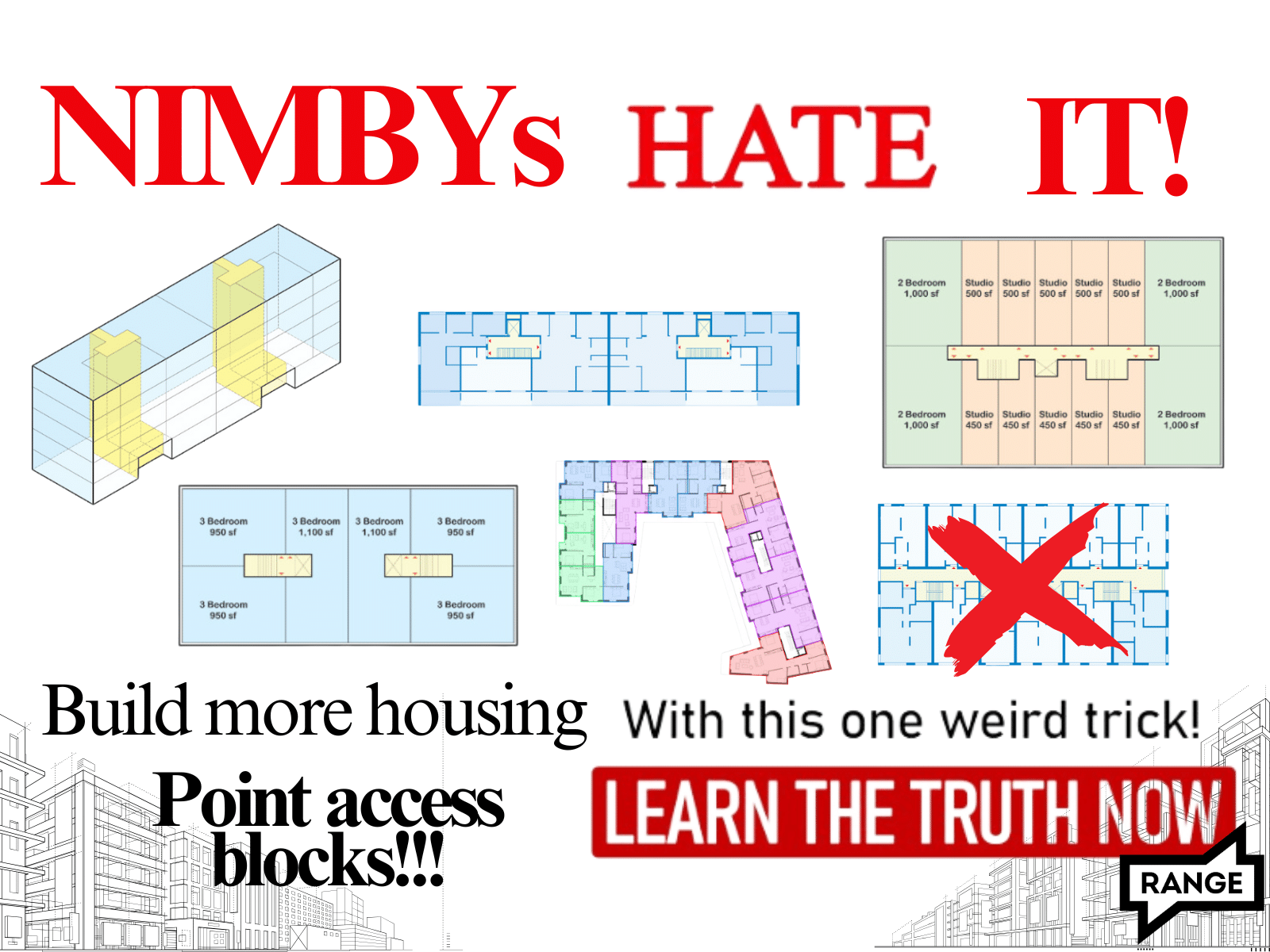

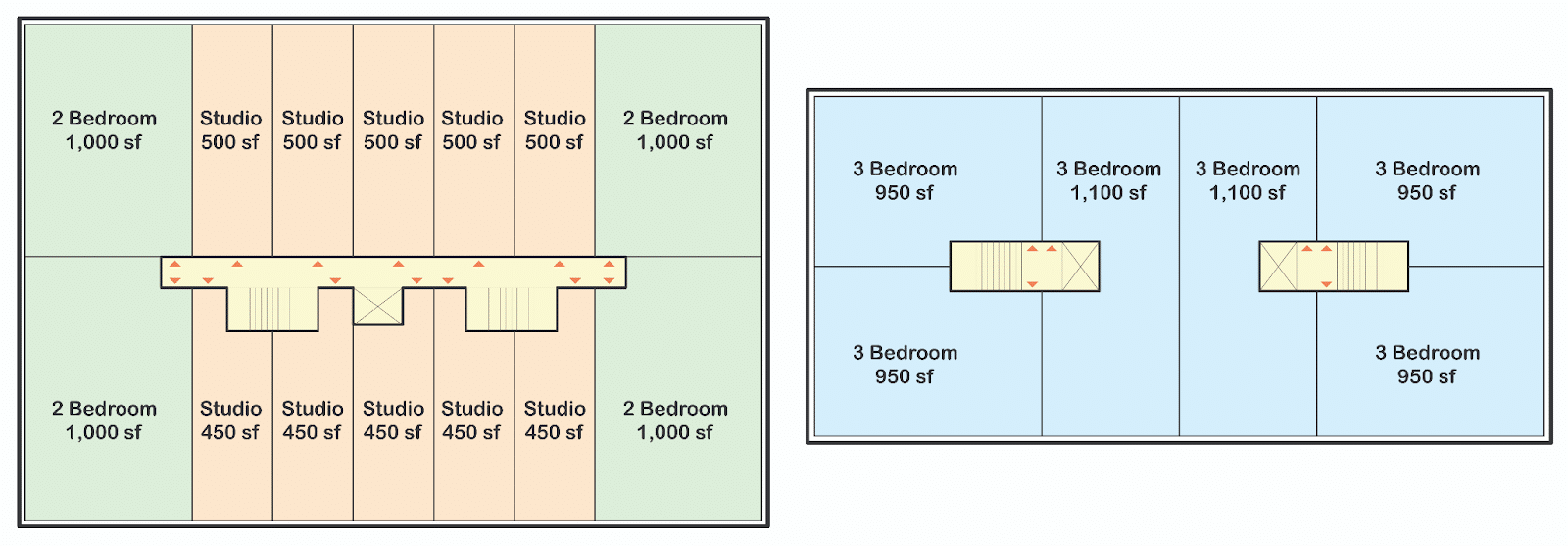

Diagram by Michael Eliason/Larch Lab

This two-stairway arrangement typically results in:

- A large building sporting one long corridor with apartments on either side, like one might see in a hotel. These are called “double-loaded corridors”.

- Mostly studios and one bedroom units, which don’t tend to serve families well.

- Units with windows on one side only, eliminating the possibility of cooling cross ventilation that can save as much as 80% on cooling costs. And north-side units miss out on warming sunlight during the winter.

- Larger apartment projects because the long corridor isn’t rentable space, and developers need to make up for the cost of building that space. When projects need to be larger, they tend to require the developer to buy up multiple parcels (“land assemblage”), which is yet another hurdle for housing development – small infill projects are one way out of our housing crisis.

- Less communal space because the long corridor takes up space in the building’s lot that could be dedicated to things like courtyards or green space – perks that are good for families.

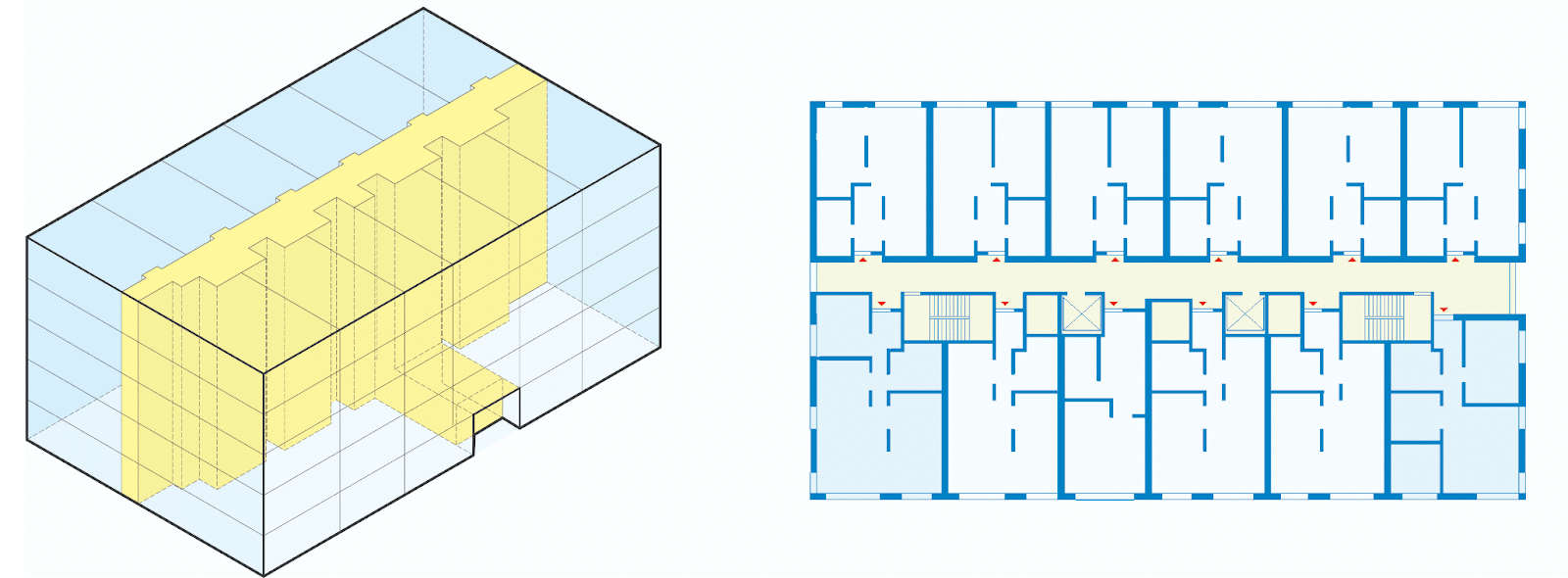

The Warren, a newer 139-unit apartment building in downtown Spokane, consists entirely of studio, one-bedroom and two-bedroom units. The architects were of course bound by the city’s current stairway code, so they designed a double-loaded corridor. On the fourth floor, 20 of the 28 units have windows on only one side.

Beyond just new buildings, our current code also impacts redevelopment of historic Spokane buildings: Josh Hissong, founder of local architecture firm HDG Architecture, told KXLY in November that it’s a “huge expenditure to bring a building up to code for life and safety.” To add a second stairway to older, brick buildings is difficult, Hisson said, which can also de-incentivize redevelopment.

So if the double-stairway codes have such significant downsides, what’s the alternative?

The point access block

All across Europe and Asia, you see five- and six-story buildings with only one stairway (or if they have two stairways, they aren’t connected by a corridor). They have a fancy name (“point access blocks”) because each dwelling unit is accessed from a single access point (think stair and elevator lobby) rather than a corridor.

This isn’t just in other countries: Seattle's building code has allowed certain six-story point access blocks since the 70s.

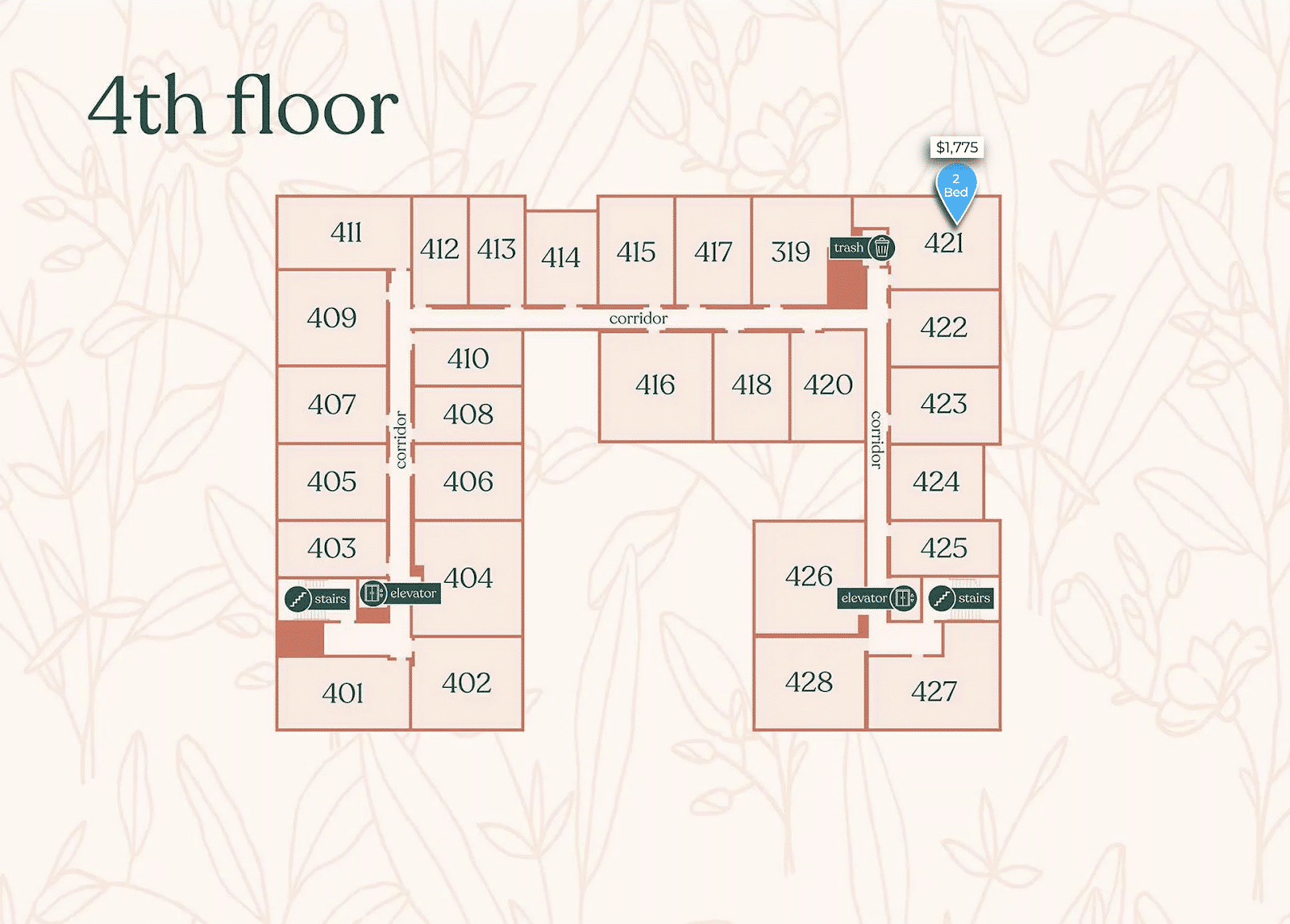

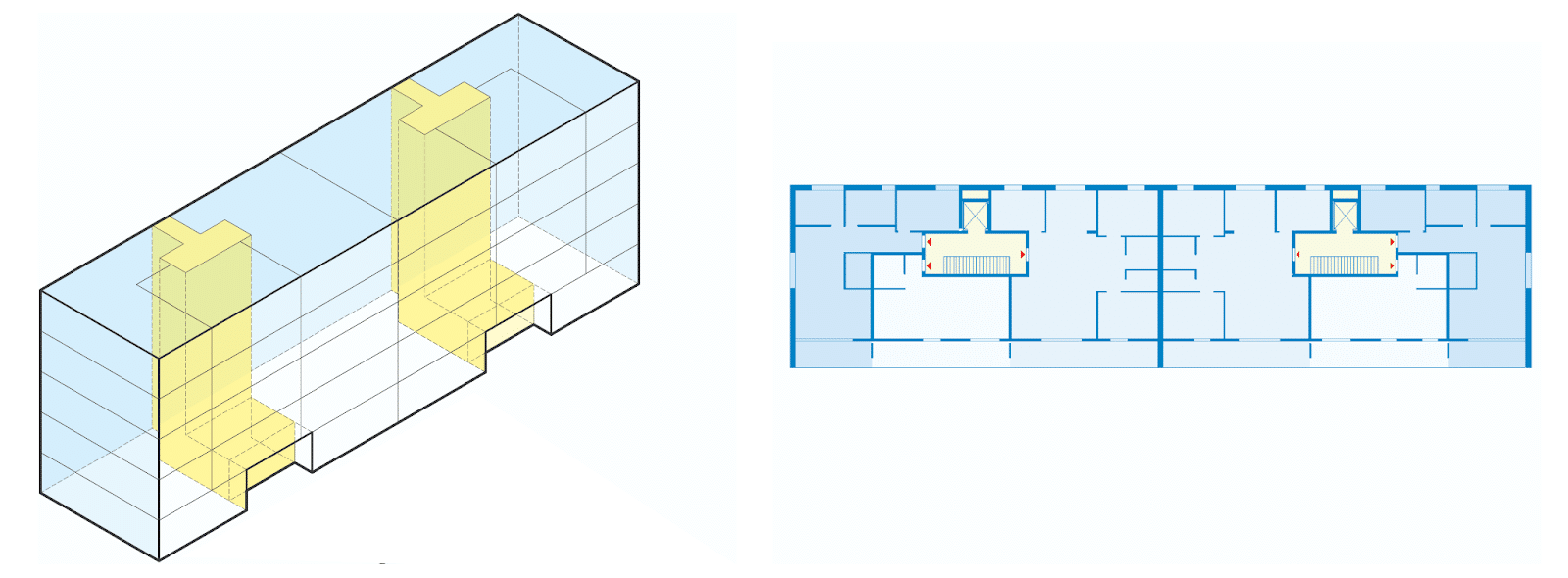

Diagram by Michael Eliason/Larch Lab

Benefits of point access blocks:

- Units can have windows on multiple sides, which allow the cross ventilation discussed above.

- Bedrooms in these units can be placed away from the arterials the buildings sit on.

- No long corridor saves room on the lot for larger units or amenities, like courtyards.

- Units can be family-sized (two- and three-bedroom units).

- Buildings can be built on smaller lots.

A comparison of the unit types that tend to get built in double-loaded corridor buildings and point access block buildings. Diagram by Michael Eliason/Larch Lab

One might be (understandably) concerned about the fire safety of having fewer stairways. The thing is, the US has a lower death-by-fire rate than some countries that allow fewer stairways, and a higher rate than others — indicating that the number of stairways may not be as correlated to fire safety as we might think.

We made risk tradeoffs every day — we don’t live in little plastic bubbles. For instance, it would be safer to build our single family homes with fire suppression sprinkler systems. But we don’t, because we’re not willing to put up with the added cost or poorer aesthetics or whatever. And most of us drive on our roads, where 40,000 Americans die every year. We make calculated safety risks all the time.

In the case of housing, America’s risk aversion regarding stairways has cost us, making housing harder to build and more expensive and family-sized units more scarce.

Local examples – yes, this affects Spokane

In reality, Spokane’s building code does allow point access blocks to be built, but they are limited to just three floors.