Jeffry Finer, who represents Jewels Helping Hands, said that judgment was a win for Jewels Helping Hands because they’ve been asking police to intervene at the camp for months to no avail. Smithson, the interim city attorney, said that the ruling gives the Spokane Police Department clearer legal guidance that will allow them to be more responsive to calls from the camp.

In addition to issuing the restraining order, Polin “reserved” judgment on the city’s suit seeking to remove the camp through the abatement process. Polin set a date, April 19, for the city and state to come back to court with a plan to close down the camp.

When Spokane’s interim city attorney, Lynden Smithson, filed suit against the State of Washington and its Department of Transportation (WSDOT) on Monday to have Camp Hope declared a nuisance, the suit contained dozens of sworn affidavits from business owners, neighbors and even employees of contractors working at Camp Hope, describing a broad range of horrific crimes committed at the camp and the negative impacts the camp has had on the surrounding neighborhood.

RANGE has since learned that at least one person, Timothy Morgan, has recanted parts of his affidavit the city presented, and contends that he didn’t write everything in the statement. “My opinion is the wording was changed to best suit and benefit the needs of the city,” Morgan said. “It’s not what I said verbatim. It’s what I said twisted.”

One line that sticks out in his statement for the city, which Morgan said he doesn’t agree with is: “Despite the fences, badges and curfew, the camp is still lawless.”

The fence, badges and curfew went into place in early November as the state started spending money directly at the camp through its subcontractors. Morgan said he gave his testimony to the city attorney in September, before any of those changes had been made.

Morgan said the affidavit broadly reflected the situation on the ground in September, but since the state and its local partners installed a fence and began controlling who comes and goes, the situation has changed. He said he is now in favor of the process in place at Camp Hope and does not think it should be shut down prematurely.

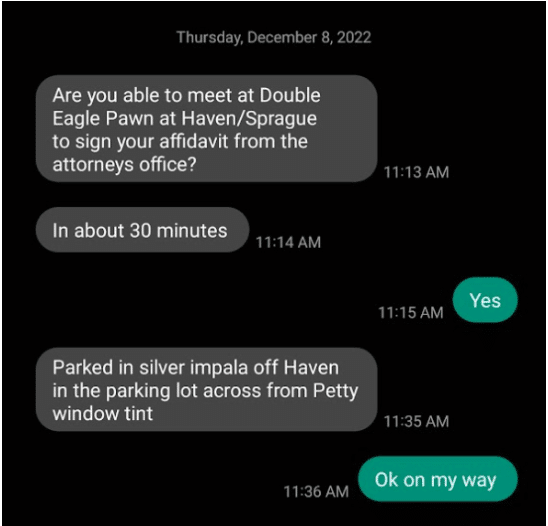

Morgan said he didn’t read the city affidavit before he signed it in December, and that he wasn’t asked to. Morgan met with a notary at a pawn shop in December for his signature.

Interim City Attorney Smithson said that in general they talk with people and go over the testimony on the phone before having them sign it.

While the City’s renewed efforts to have Camp Hope declared a nuisance came as a surprise to most people we’ve spoken with, Morgan’s story demonstrates that the city has been building its case since it first declared the property a nuisance in October of 2022. It also appears to show that the city attorney’s office didn’t check back in with people about testimony they gave months prior, even as the camp shrunk by over 85% to just 65 individuals currently.

Now, Morgan has provided a second affidavit in support of the legal case put forth by the state, which asks the court to let them and their local partners continue the process of moving people off the camp.

Morgan said he agrees with that signed testimony “110%.”

That statement hews a lot closer to what Morgan told RANGE last month. In February, Morgan was clear-eyed about what he saw in his time as a security guard, but also how the camp had transformed from a lawless community to a place where people were could get help once state money began to flow and camp organizers put in place a more rigid structure, including enclosing the camp with fencing, giving each resident a badge, not allowing new people to join the camp and requiring people to show their badges to enter the encampment.

“Before the fence, badges and curfews it was a lawless community,” Morgan told RANGE this week. “Not after.”

Throughout this process, both sides have used Morgan for their case and have not taken care to protect Morgan from the ramifications of this testimony. And, those ramifications of the original affidavit have been dire.

Morgan told RANGE he lost his job with Revive Counseling today, apparently for including the names of company clients in the city affidavit. Because Revive bills Medicaid for some of its services, those names should have been protected under Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which Morgan was bound by at the time as an employee for Revive.

But when he gave the original statement, he wasn’t working for Revive. “I had no knowledge of violating [HIPAA] because I worked for CMS when I wrote it,” Morgan said. He also said he felt obligated to provide evidence for the city because his employers were contracted by them. “I worked for CMS, should I tell them no?”

“I’m just a normal guy, I don’t have common knowledge or understanding of those kind of things.”

Because no one at the city protected or advised Morgan of his potential legal liability and he is out of a job and worried about his family. And because he named names, Morgan is also worried about his safety and property.“Now, I wonder if people will come slash my tires and try to figure out where I live,” he said.

When Smithson heard Morgan had lost his job he said he was disappointed to hear that Morgan’s livelihood had been jeopardized by his testimony. Smithson pledged to put in a call to Revive or, barring that, try to find Morgan work, and mentioned Salvation Army, which runs the TRAC Shelter.

“It's not our intent that someone who wants to help won't be able to help,” Smithson said. “That's not okay at all, and not what we want to do.”

For now, finding a new job is Morgan’s priority. “I’m going to search for work,” he said. “I’m still going to try. I have to protect my family first and foremost.”