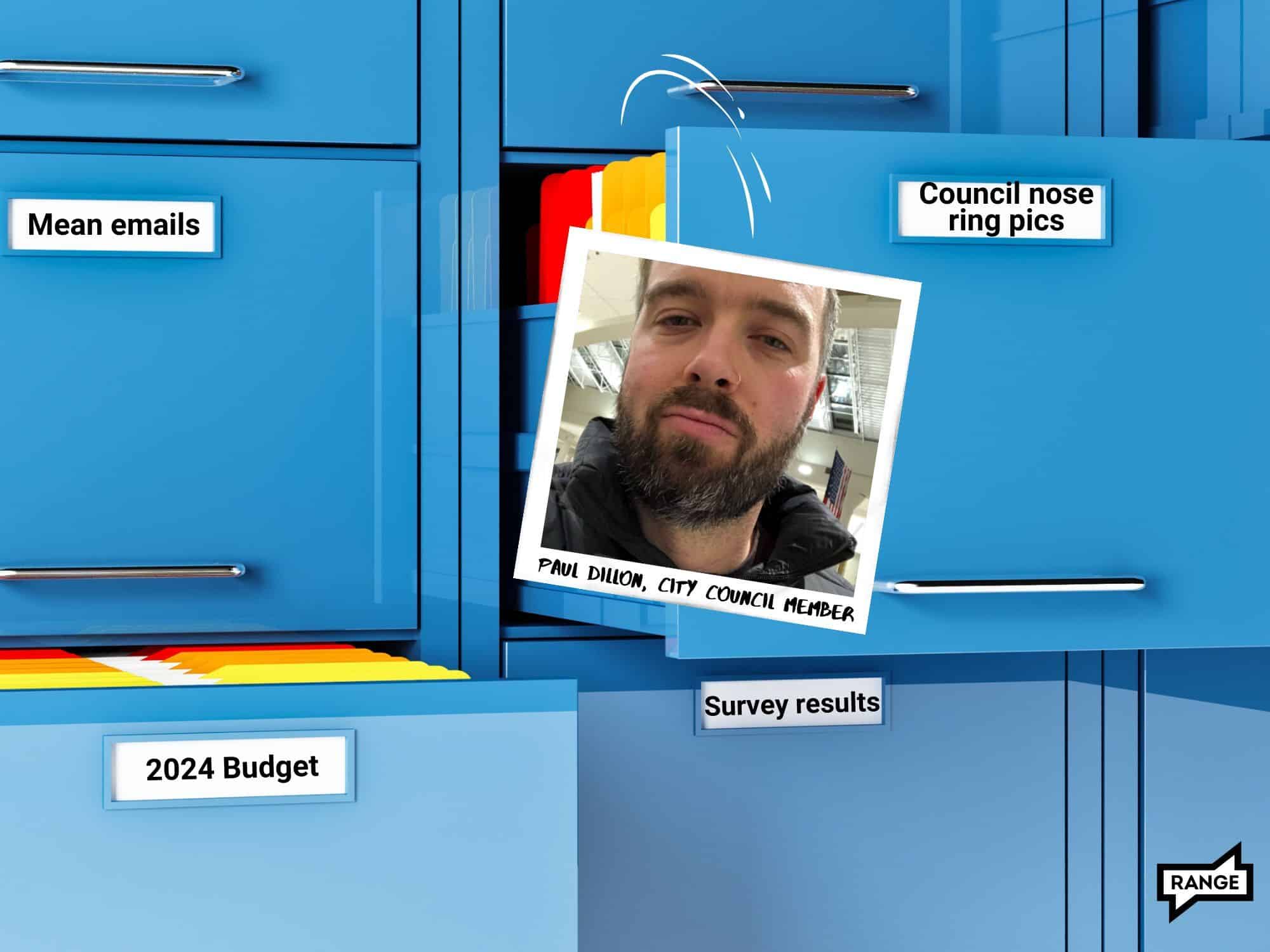

This photo could be obtained in a records request.

This photo could not.

While the difference in this case is relatively clear — the first of these photos was posted by a politician on his council member Twitter account and the second is a janky Photoshop produced in-house — the nuances of what can and can’t be obtained through public records requests (PRRs) can be complex.

Much of our recent coverage of local governments has leaned heavily on information obtained through PRRs. It was a records request that revealed the Spokane Transit Authority (STA) had asked guards to follow a local transit safety advocate because he gave pointed public testimony. It was a PRR that uncovered more insight into Dr. Bob Lutz’s resignation from his position as the region’s medical officer for the State Department of Health. And, it was public records (though obtained from sources, not an official request) that provided the evidence to back up the story of Mead school teacher Jacob Knight, who found his work environment grew less and less friendly after he came out as gay.

Pretty much any information that passes through a public channel — including e- and snail-mail inboxes, phone numbers, social media accounts maintained by public officials — is required by state law to be disclosed when someone asks for it. Maybe that information is sent carelessly — like when County Commissioner Al French sent texts making jokes about transgender people and demeaning fellow STA board members. Or maybe the sender just isn’t aware what information is fair game for people to ask for.

But whatever the reasons a piece of public information exists, the public records request is a powerful tool for anyone who wants to go digging for information. Whether you’re a records-requester-hobbyist or someone who frequently communicates with government officials, we hope this guide will help you engage with government systems in a more informed way.

First, the basics.

According to the Washington Coalition for Open Government (WashCOG), public records are defined broadly as “all records, document, tape, or other information stored or preserved in any medium” — including on a computer — “of or belonging to” a government agency.” To get more precise with the definition, under state law, a piece of information must contain all of the following three elements to be considered a “public record” and thus, requestable*:

- It must be “a writing”: Think emails, texts, reports, presentations, etc. However, recordings of communication or sound, and photos or videos sent or maintained by a government agency also qualify as “a writing.”

- The “writing” must be related to the conduct or performance of a government agency. The state interprets this broadly though, because virtually every document maintained or kept by a government agency relates to their conduct or function.

- The “writing” has to be created by, owned by, used by or retained by the agency it’s requested from. If an agency uses academic research in the preparation of a report, for example, that research could be requestable.

* Note: we’re using the word “requestable” throughout this guide to denote what public agencies are typically required to disclose, though there are exceptions and nuances to every rule.

Anything defined as a record must be retained for set periods of time and destroyed only in ways allowed in state law.

Some of the obvious and most frequently requested public records include email correspondence between lawmakers, written incident reports or HR complaints and documents like contracts the government holds with businesses or nonprofits. The results of surveys conducted by the city or other public agencies, meeting minutes and meeting recordings are also pretty straightforward examples of records someone could request.

Police records are also huge. Both the Spokane Police Department and the Spokane Sheriff’s Office are government agencies, which means their records are public and requestable. Body camera footage, police reports and details of 911 calls can all be requested by the public and most often must be disclosed. There are some exceptions to this rule. For example, records relating to open investigations can be kept secret to maintain the integrity of the investigation.

Financial records from these entities are also requestable; if you were curious how much the Spokane Police Department spends on settlements, they’d have to tell you. (Wording here is very important — something like, “all settlement agreements made by the Spokane Police Department in 2023” would do the trick while “how much money has SPD spent on settlements?” might not.)

The not-so-obvious

There are other less obvious records that are considered public records — like that first photo of Spokane City Council Member Paul Dillon wearing a nose ring, which he tweeted from his council member-specific social media account.

Because the account is linked to his office as city council member and because he uses it to share information in his capacity as an elected official, all social media postings from that account are fair game for public records requests. Social media rules are a little tricky — if Dillon posted that photo from his personal Twitter account, the city would not have to provide it. However, if he posted information in his capacity as a council member, like his customary meeting recaps, on his personal account, that post might be something you could request.

We’re picking on Dillon, but other city council members maintain social media accounts tied to their positions, like the “Councilman Michael Cathcart” and “Councilman Jonathan Bingle,” Facebook accounts. Information from social media accounts tied to a public office that can be subject to public records requests include:

- Direct messages sent to and from the account

- Search history on the platform from the account

- All posts and comments made by the account (though people requesting posts generally need to identify specific keywords they’re interested in)

- And, all “liked” posts by the social media account.

Aside from social media, there are a few other not-so-obvious realms of information that are fair game to records request.

We frequently request correspondence sent by politicians or government employees, but did you know correspondence sent to those same officials will turn up in records requests, regardless of who sent it? If you’ve sent an email advocating for a policy, complaining about a decision a government body has made, confessing your love (or hate) for a public official or asking for the pothole in your neighborhood to get fixed, those communications generally must be disclosed, because they are retained or used by the agency.

There are also people who count as government officials that you might not expect — like school district employees.

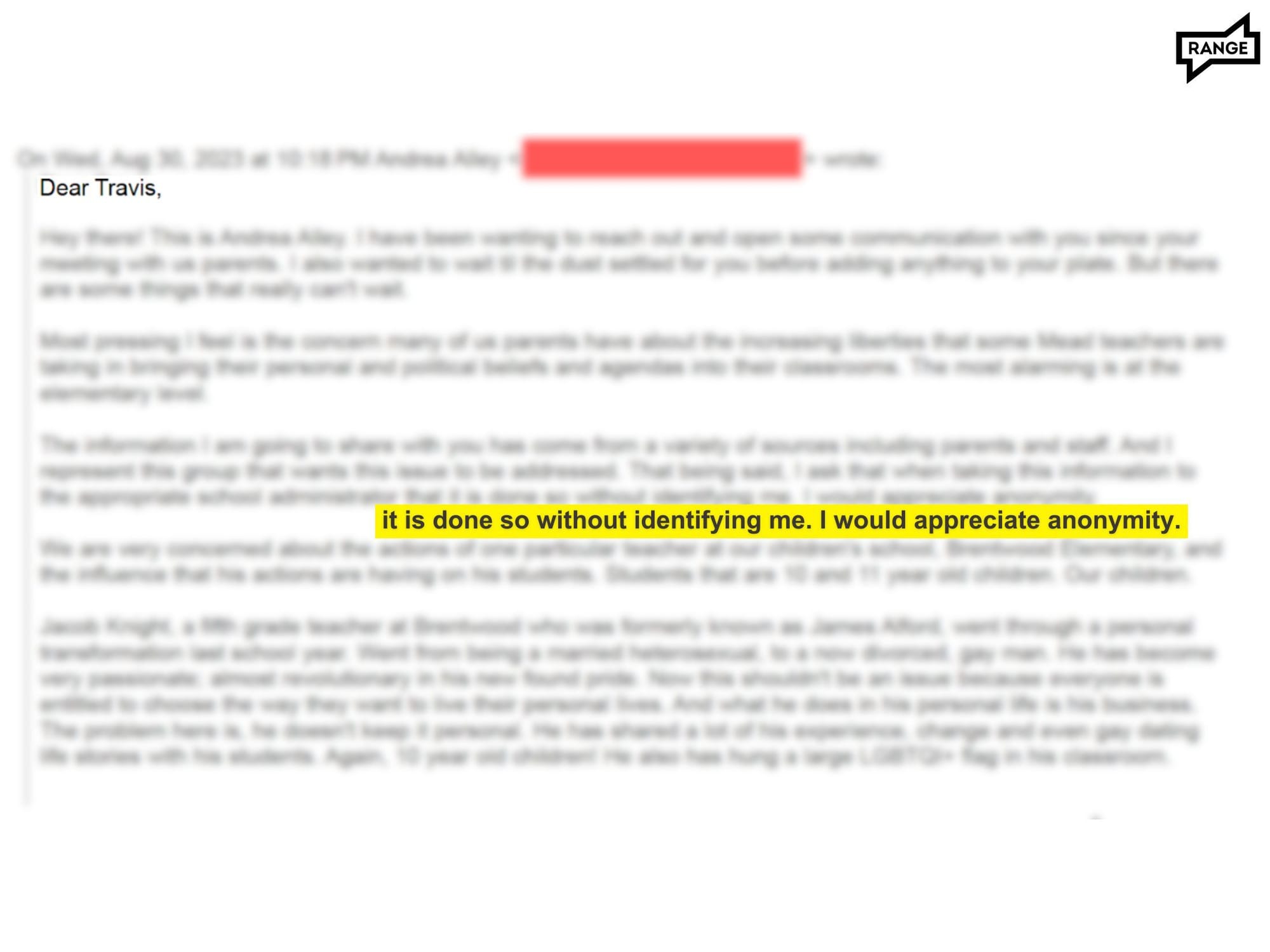

RANGE recently obtained multiple emails sent to staff at Mead School District (MSD), including from a parent who asked the superintendent for anonymity. That email came from parent Andrea Alley, who wanted her complaint to superintendent Travis Hansen about the presence of a Pride flag in Knight’s classroom — which she called “grooming and child abuse” — to remain anonymous. Regardless of the sender’s preferences, though, when Mead responded to the records request, it included this email with no redactions at all, even the sender’s email address (which RANGE is choosing to redact to maintain a modicum of privacy).

Such emails are maintained by MSD as records which can be requested, which means the district cannot honor requests for anonymity — something you should note if you’re emailing government employees.

Other interesting and lesser known records you can request, some of which RANGE has asked for previously, include:

- The names of all speakers who signed up to testify at public meetings. Some government agencies even require speakers to sign in with a full legal name and their address. We’ve requested these lists before to ensure we’re spelling names correctly in published pieces.

- Hyper-specific keyword searches, like all usages of “RANGE,” “RANGE Media,” or “Erin Sellers” in emails, text messages and written communications of Spokane city employees.

- Text messages, call logs and search histories on agency-provided devices (and work-related text messages on personal devices) — the rules have evolved to include modern communication technology.

- Digital and written calendars for government employees.

- Records requests submitted by other people. For example, if you’re curious if a politician or public figure has submitted a request to a government agency, you can request “all records requests filed by Lisa Brown,” or, if you’re curious what other folks are working on, all records requested by other activists, journalists or other sleuths. You could even request all records RANGE has requested, though you’d have to break it down by journalist’s name.

At RANGE, we believe that more information and transparency is always a good thing, so if all this information has you jumping to request records (and hopefully has you primed to be mindful about what you’re sending to government employees work devices/accounts), here are some local agencies you can submit public records requests to:

- Spokane City, which encompasses city council, city administration and Spokane Police Department

- Spokane County, which encompasses the Board of County Commissioners, the county courts, the county Sheriff’s Office and 911 calls to Spokane Regional Emergency Communications (SREC)

- Spokane Transit Authority

- Spokane Regional Health District

- All regional school districts (Spokane Public School District, Mead School District, Central Valley School District.)

Be cautious, and happy hunting!