“When I moved up here to Spokane, I had never been exposed to transgender women or people, at all,” Crystal Marché says, telling a bit of her own story of moving to Spokane in the early 2000s as we survey hundreds of years of local queer history.

“We were really poor, and five drag queens slept in one house. So we would go to Molly's, and Molly's was really inexpensive to eat at at the time,” she says. That relative poverty was a bit of fate for Marché and her friends, because it was there they met their people. “And Thursdays, every week, a group of transgender women would meet there. They just wanted to meet up and have camaraderie.”

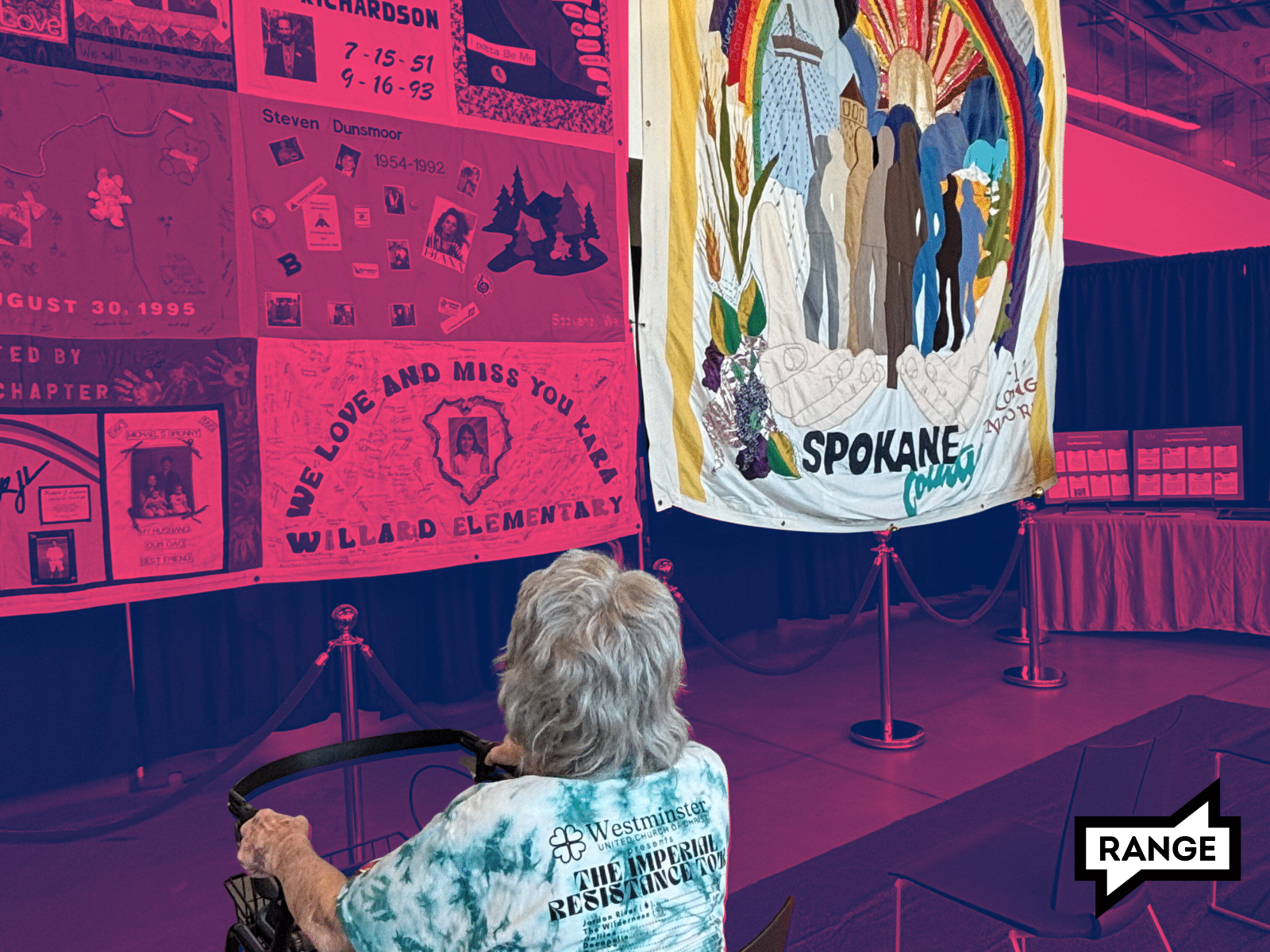

Marché is the head curator of The Pride History and Remembrance Project — a project she worked on with exhibit archivist Bethany Laird — to connect the camaraderie she felt when she first moved to Spokane with joy on display at this past weekends pride and back to a history that predates the colonization of the Americas.

Prior to working on the project, both organizers had learned bits and pieces of recent 2SLGBTQIA+ history from members of the local community, but it often came without a comprehensive, historical look at queer life in the city.

For Marché, these informal history lessons looked like meals with local transgender women at downtown diners, where food was inexpensive and served with a side of advice. Laird’s education, on the other hand, took the form of what they called, “all the queer extracurriculars,” from Queer Comedy Nights to “Queer Craft Club meet-ups.

Marché, a local drag performer, found that elders within the queer community imparted their lived experiences to her and others as kernels of knowledge that not only bonded a community, but also educated young people.

She realized, though, that these histories could only travel so far when whispered over a dinner table. She wanted to take those stories and weave them into a more formal historical narrative.

“My elders tell stories. And so I’ve learned all of these deeply nuanced stories from all these wonderful people,” Marché said. “They can tell you about things that many of us never even knew about the struggles and what it was like to take up space in a time when we really didn’t take up space.”