Less than 37% of Spokane-voters cast a ballot in this year’s primary election. If history is a guide, this low turnout is likely to improve in November’s general election, but not by much. In 2019, just over half of Spokane city voters made their voices heard in the election for the two most important offices in city government — the mayor and city council president.

This low turnout may seem like an outlier for Washington. After all, more than 75% of Washingtonians voted in the 2020 election, making Washington one of the top five states for voter turnout nationwide. But, for all the successes of the state election system in federal elections, far fewer people vote in odd years when all city elections statewide happen. In 2021 for example, less than 37% of Spokane County voters voted in the general election, a far cry from the nearly 82% who voted in the 2020 general election and the nearly 62% who voted in the 2022 general election.

Across the country, and more recently across the Cascades in King County, local and state governments are taking a simple step to improve voter turnout: moving odd-year elections to even years to sync up with federal election cycles. With the lackluster turnout in last week’s elections, we wanted to examine the potential impacts of syncing local elections with federal election cycles, what that could mean for politics and representation in Spokane, and what it would take to shift Spokane elections to even years.

More people vote in even-year elections

Recent election turnout numbers in Spokane show a sharp contrast between voting in odd and even years. In the 2020 election cycle more than 80% of Spokane City voters voted in the general election. In the city of Spokane, about 50% of voters filled out a ballot in 2019.

Local turnout is even worse when the mayor and council president positions aren’t up for grabs. In 2021, when 3 of the 7 Spokane city council seats were on the ballot, only 37% of voters cast a vote — less than half the number who voted in the city in the 2020 election when federal elections, including the presidency, were on the ballot.

Every little bit seems to help. Presidential elections only come around every four years, but we have congressional races every two. In 2018, the turnout was nearly 73% and in 2022, it was nearly 62%.

This isn’t just a Spokane thing. It’s true across the Northwest and the country as a whole. For a regional comparison, Alan Durning, the founder and executive director of the Sightline Institute think tank, looked at Oregon’s municipal elections as part of a series promoting even-year elections in Washington.

In Oregon, city elections occur in even years. Durning’s comparison of recent elections in the largest cities in Washington and Oregon found that Oregon cities had “93% more turnout, as a share of eligible voters, than their Washington counterparts.”

A common concern with adding more elections to even years when federal elections take place is that ballots with more races will lead people to not vote in each specific race. But, a comparison of some of the most influential offices in Spokane — the Spokane City Council and Spokane County Board of Commissioners — shows that the impact of people not voting in every election on the ballot is minimal compared to the improved turnout in even-year elections.

After undervotes were removed from turnout totals in the 2021 council races that were contested, 26% of Spokane Council District 1 voters cast a ballot in the race between Jonathan Bingle and Naghmana Sherazi and 40% of District 3 voted in the council race between Zack Zappone and Mike Lish. In each of those races, less than 1% of voters didn’t cast a vote but voted elsewhere on the ballot.

In the 2020 County Commissioner races, which occurred during a presidential cycle, there was a larger percentage of people who did not vote — around 5% or 20,000 voters — but the turnout was still 76% in the commissioners races between Josh Kerns and Ted Cummings, and Mary Kuney and David Green. Even with voter drop-off, far more Spokanites participated in the local elections that coincide with federal elections.

Razor thin odd-year elections, clear partisan advantages in federal election years

In 2019, both Mayor Nadine Woodward and Council President Breean Beggs prevailed in nail-bitingly close elections. Woodward bested Ben Stuckart by 849 votes, while Beggs topped Cindy Wendle by 957.

Although those races are nominally nonpartisan, there were clear ideological differences between the candidates. And, the close races make it appear that the City of Spokane is about a 50/50 split of liberal and conservative voters. That pattern does not hold true in federal election years.

The city of Spokane overwhelmingly voted Democrat in 2020. Joe Biden beat incumbent Donald Trump by 17 points. Jay Inslee bested Loren Culp by 12 points. Dave Wilson edged out congressional representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers by 2.5 points in an election where she was a runaway winner across Eastern Washington.

The 2022 county commissioner elections, the first since the commission expanded from three to five members, echoed the partisan dividing lines in Spokane County. In Districts 1 and 2, which cover most of the city of Spokane, Democrats Chris Jordan and Amber Waldref won by about 10 points each. Conservative commissioner Al French, whose district includes part of the city, won by about 3 points in District 5. The other two districts only sent Republicans to the general election.

That partisan advantage in the city held in the federal election year of 2022 where County Auditor Vicky Dalton won the city by 23 points propelling her to a narrow victory countywide. Natasha Hill, who lost by a considerable margin in the district-wide race, blew out McMorris Rodgers in the city of Spokane by 11 points.

These results paint a picture of a city that’s reliably blue when voters turn out, but where Democrat turnout isn’t reliable in odd-year elections. In 2019, less than 69,000 people voted in mayoral and city council president elections that split liberal and conservative with margins of less than 1,000 votes. A year later, 50,000 more Spokanites voted with a clear preference for liberal candidates.

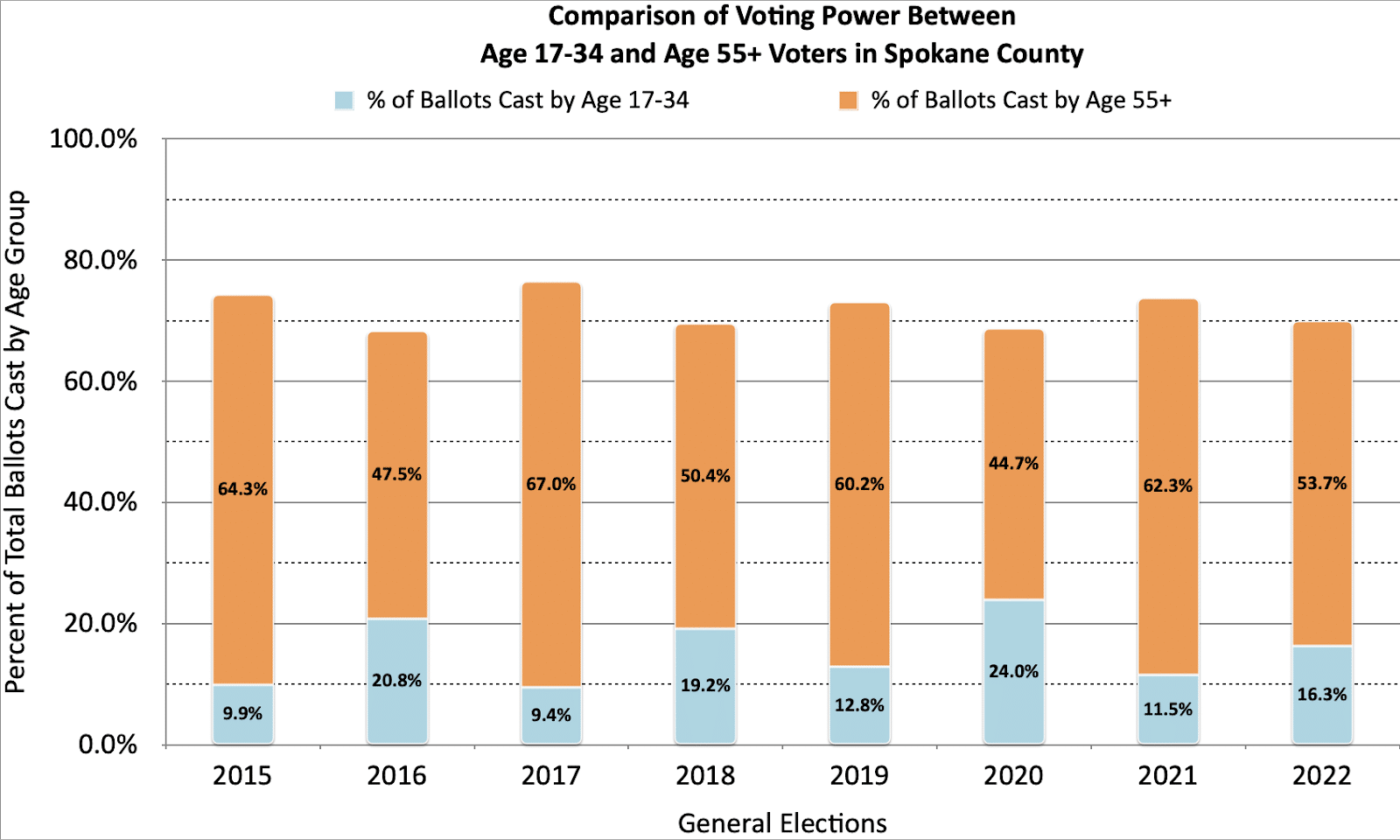

While we can track the influence of the liberal vote fairly clearly in municipal elections, it’s harder to parse city turnout data by age. But the closest available proxy, county data, shows that younger voters have significantly more influence in even year elections, with numbers nearly doubling in presidential election years.

That’s a trend that holds true across elections in Washington. In testimony in support of a King County referendum to move county council elections to even years, University of California San Diego professor Zoltan Hajnal wrote, in part, “residents over 65, whites, and the wealthy are greatly overrepresented” in odd-year elections. Washington voters ages 18-24 voted in only 18% of odd-year local elections, whereas in even years, 50% of younger voters cast a ballot, Hajnal testified. Older voters cast ballots more consistently and thus have a greater say in odd year elections when young people are less likely to vote.

Writing for the Cambridge University Press, Hajnal underlined the implications of these findings. “Considerable research shows that on-cycle (even-year) November elections generally double local voter turnout compared with stand-alone local contests.” That higher turnout “leads to an electorate that is considerably more representative in terms of race, age and partisanship.”

‘There’s no simple answer’

While academic research and local data points to improved turnout in municipal elections in even years, there’s a host of potential downfalls to loading up even year ballots with more races. Moving more races, especially for high-profile elections like the Mayor of Spokane, could mean that already low-turnout elections in odd years get even worse, said Vicky Dalton, the Spokane County Auditor.

Focusing on turnout in the most influential local offices loses sight of the impact on other lower-profile elections, Dalton said. “What's the impact on schools, water districts, sewer districts, fire districts?” she said. “You're looking at a tiny slice, look at the big picture: What's the damage that's gonna be done to the other jurisdictions?”

“There's no simple answer,” Dalton said. “Every ‘solution’ has consequences and risks. Those need to be reviewed.”

Dalton also questioned the impact that consolidating elections would have on people running for office. “If you start putting all these, shall we call them premier races, all on the same year, all on the same ballot, you are forcing the candidates to compete for money to do their campaigns,” Dalton said. “You're making it harder for messages to be heard by the voter because there's just too many messages happening at the same time.”

That situation might lead to more turnout, but Dalton questioned the quality of that turnout. “Maybe more people are going to mark a ballot, but are they necessarily doing the research?” she said. “Are they informed voters?”

Ultimately, Dalton said she’d rather see a focus on improving turnout in odd years than a shift to even-year elections for municipal races in Spokane. “Quite frankly, I would want to have people turn out in the odd years as well as the even years,” she said. “That would be the best solution.”

Getting even

Last year, voters in King County were asked whether they supported moving the elections for King County’s executive, assessor, director of elections and council members from odd-numbered to even-numbered years. Their answer was a resounding yes. The initiative passed with nearly 70% of voters approving the change to even-year elections for the county’s most influential offices.

While King County voters were able to decide on the switch to even-year elections, Spokane City voters don’t have the same initiative power. That’s because state law requires cities to hold general elections in odd years.

For the last five-plus years, Durning and other election reform advocates have been pushing for the legislature to give Washington cities the ability to sync their elections up with the federal election cycle. But, the issue has never made it to a floor vote.

Durning doesn’t believe there is outright opposition to the idea, but more an issue of inertia. “Most of the barrier has just been inattention, not blockage,” he said. “No state legislator goes home and has a line of people at their community forums demanding to reschedule elections.”

While the issue hasn’t gotten traction in Washington, it’s recently caught on in other Western states. Since 2015, California, Arizona and Nevada have adopted legislation to either encourage or require cities to move to even-year elections.

Notably, these changes have been driven by unique political coalitions in each state. Democrats backed changing election laws in California, in Arizona the switch was backed by Republicans and in Nevada the change was adopted with bipartisan approval.

In King County, the switch to even-year elections will be phased in over the course of the next five years with a full transfer to even-year elections in 2028. Candidates in this year’s election cycle and in 2025 will be running for truncated 3-year terms as the switchover goes into effect.

King County Election Director Julie Wise said the impacts of the change won’t be felt by her office until they go into effect, but that they’re mostly about practical issues like how long a ballot is or how much paper they use. “Only moving two to four races for each voter, I'm not sure there's going to really be a huge impact,” Wise said. “I am a big believer that democracy is at its finest when all voices are heard.”

“If there's any ability to look at something that could increase turnout, that's going to be of interest to me,” Wise said. “In odd-year elections, we celebrate if we crack 50% — I think it's reasonable to ask if that's democracy.”

Additional data reporting for this story contributed by Logan Camporeale.

Editor's note: This story previously misnamed Dave Wilson as Doug Wilson.