The conservative Spokane County Board of County Commissioners and relatively more progressive Spokane City Council have long butted heads. Whether it’s the Spokane Transit Authority board, the Spokane Airport Board or the Spokane Regional Health District Board (SRHD) — all entities that make key decisions that shape policies and lives across our community — the political tug-of-war between has often overshadowed conversations about the common good.

The most widely-known — and perhaps most-consequential — of these fights was catalyzed by the decision to fire Spokane County health officer Bob Lutz in 2020, amid the COVID-19 shutdowns and subsequent political protests to push back on government mandates and reopen businesses.

Lutz’ termination by the SRHD board — which was majority conservative — created enough outrage among a mix of progressive activists and public health professionals that the tug of war spilled the bounds of Spokane County and worked its way all the way to the state.

During the 2021 legislative session, District 3 Democratic Representative Marcus Riccelli put his thumb on the scale. His legislation would apply statewide, but was sparked by what he saw locally, seeking to force a restructure of the SRHD board that would balance it toward putting power in the hands of medical experts and people with lived experience by stripping seats from elected officials battling for control and politicizing health boards around the state.

But because of the way Riccelli’s bill was written, instead of creating a board with more equitable representation between the city, county and medical experts, Spokane commissioners were able to push Spokane city representatives off the board altogether. They then chose ideological allies to fill the newly minted community seats.

The BOCC won that battle, but the war for the soul of the SRHD is still underway. Spokane Mayor Lisa Brown sent an email earlier this year asking the BOCC to allow the city to choose a representative to the board. Instead, the BOCC appointed City Council Member Michael Cathcart to fill a rotating spot representing leadership of “cities and towns” — one of only two conservatives on the council — with no input from the mayor or City Council President Betsy Wilkerson.

Throughout all of this, and despite a commitment from the county commissioners to adopt the new structure and board members by January 25, 2022, one seat on the SRHD board has been vacant, and still is: a Tribal Communities position intended to guarantee representation for Indigenous people, who are often left out of and marginalized in conversations about public health. This fact was well-illustrated during the pandemic by headlines saying Native communities were routinely left behind in the response to that crisis.

After the SRHD board started the new year with a slate of appointments to fill open positions — including Cathcart’s appointment — the Spokane Documenter covering the meeting wanted to know: Why make all the other appointments while leaving the tribal seat open?

We set out to answer that question.

It’s not for lack of applications.

A project of persistence

Dylan Dressler, the clinic director for the NATIVE Project, has been trying to secure an appointment to the SRHD board for nearly four years, beginning before the mandate requiring a tribal representative even existed.

In summer of 2020, when vaccine distribution was just a vague hope for the future, Dressler had applied for a vacant seat on the SRHD board representing District 2 — an area that includes Liberty Lake, Spokane Valley and Millwood. Even though Dr. Bob Lutz, still Health Officer at the time, recommended her to the board, Dressler was not selected. She said she received a call from County Commissioner Mary Kuney’s assistant, telling her that there actually wasn’t a vacancy to fill, because Chuck Hafner — who previously held the position — had recalled his resignation.

But that didn’t discourage her.

Dressler says her first application was spurred by her long interest in Indigenous health and a desire to make a lasting impact on community health. She decided to keep applying after witnessing how COVID-19 ravaged Indigenous communities, and how — despite robust policies around vaccination and best practices — without continuous efforts from people like Dressler, state vaccination efforts would have completely failed to account for the specific needs of native communities.

The clearest example was the vaccine roll out, which, in Washington, prioritized people over the age of 65.

Dressler cited statistics showing that Indigenous people have the lowest life expectancy of any race and how, in Spokane County, race and neighborhood can mean the difference between living to 65, or living to 81. At the bottom end of that 16-year disparity are Spokane neighborhoods like Riverside, East Central and Chief Garry Park — all areas with higher than average concentrations of Black, Indigenous and People of Color.

Because the differences in life expectancy meant that when it came time for the state to tell regions how to prioritize vaccine distribution, many of the oldest people in Indigenous communities weren’t even eligible to receive vaccinations.

“Our elders are 50 or 55 and up. They're not 65. We don't live that long,” Dressler said. “When we don't have elders, we don't have culture.”

That’s why she leveraged her position as NATIVE Project clinic director in Spokane to secure a batch of vaccines from the state, and then exercised tribal sovereignty to overrule the state Department of Health regulations, which would have left out many vulnerable members of her community. Instead, the NATIVE Project’s distribution — which immunized 4,156 people by June 2021 — prioritized health care staff, those considered elders by the community, teachers and people living in multigenerational households.

“Our approach was very different because we know our community and we knew how that was going to impact us,” Dressler said. “We violated the state's regulations because those didn't apply to us. They didn't work for us.”

Dressler says witnessing how her community was left to fend for itself during the pandemic refueled her drive to be a part of the regional decision-making processes. If there was someone like her on the SRHD board, maybe state and regional regulations would have looked different. Maybe they would've protected the elders in her community.

“We're all in community together. We're not separate from one another,” Dressler said. “When we make decisions on the [SRHD] board, it should be with consideration of marginalized communities, disenfranchised communities, unhoused communities — people that really are at the highest risk of dying from epidemics and pandemics.”

In early 2022, Dressler again applied for a position on the SRHD board. This time, it was for a position that seemed tailor-made for her and what she hoped to accomplish — representing “Tribal Communities.”

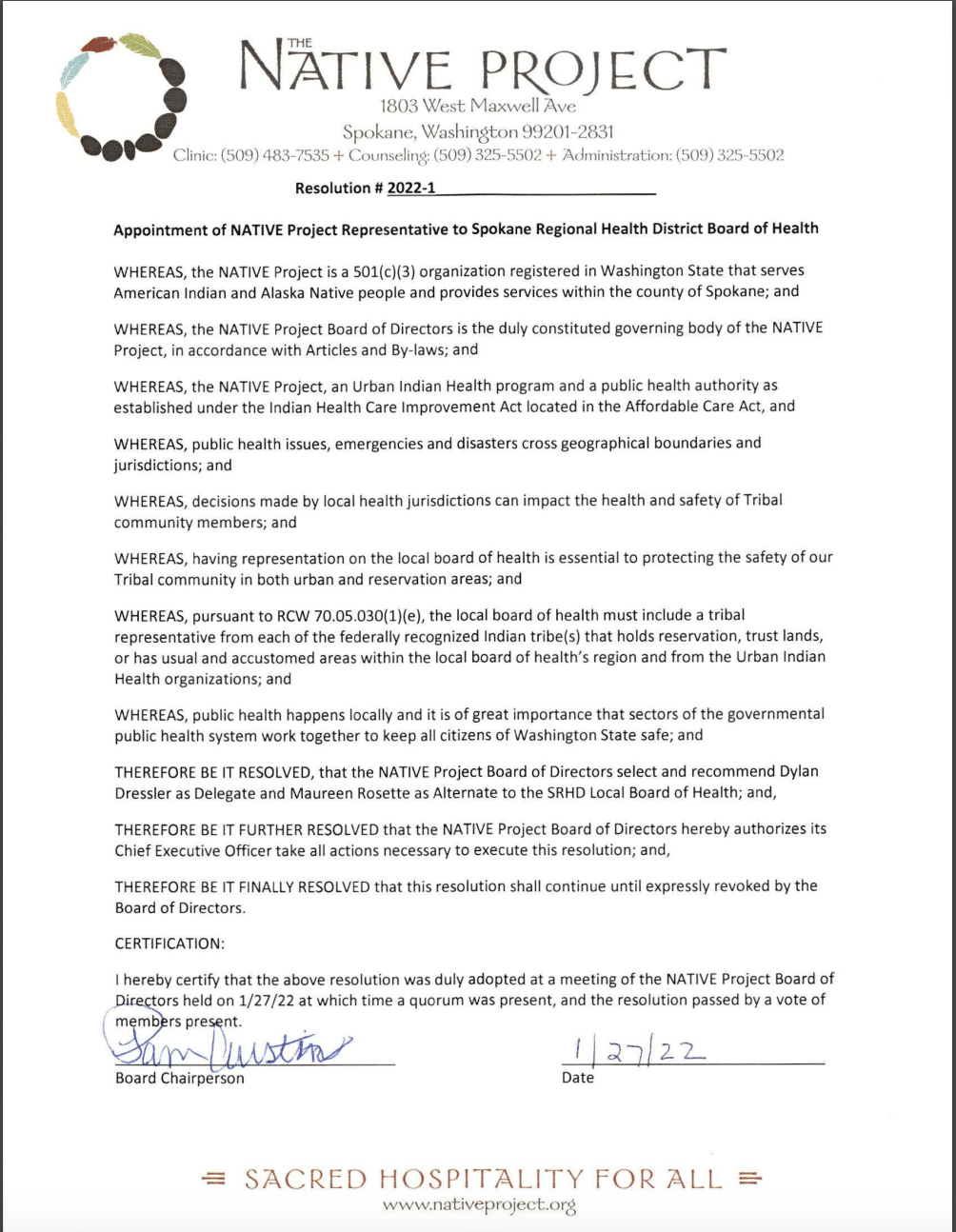

Because of the changes made in 2021 by Riccelli’s legislation, Dressler had to get a resolution of support from The NATIVE Project Board of Directors recommending her as their delegate, which she sent on January 27, 2022, per documents RANGE has reviewed.

Dressler had goals in mind when she applied to the position. She wanted “to remind our community that rugged individualism is not a good public health practice.”

‘It’s just very confusing.’

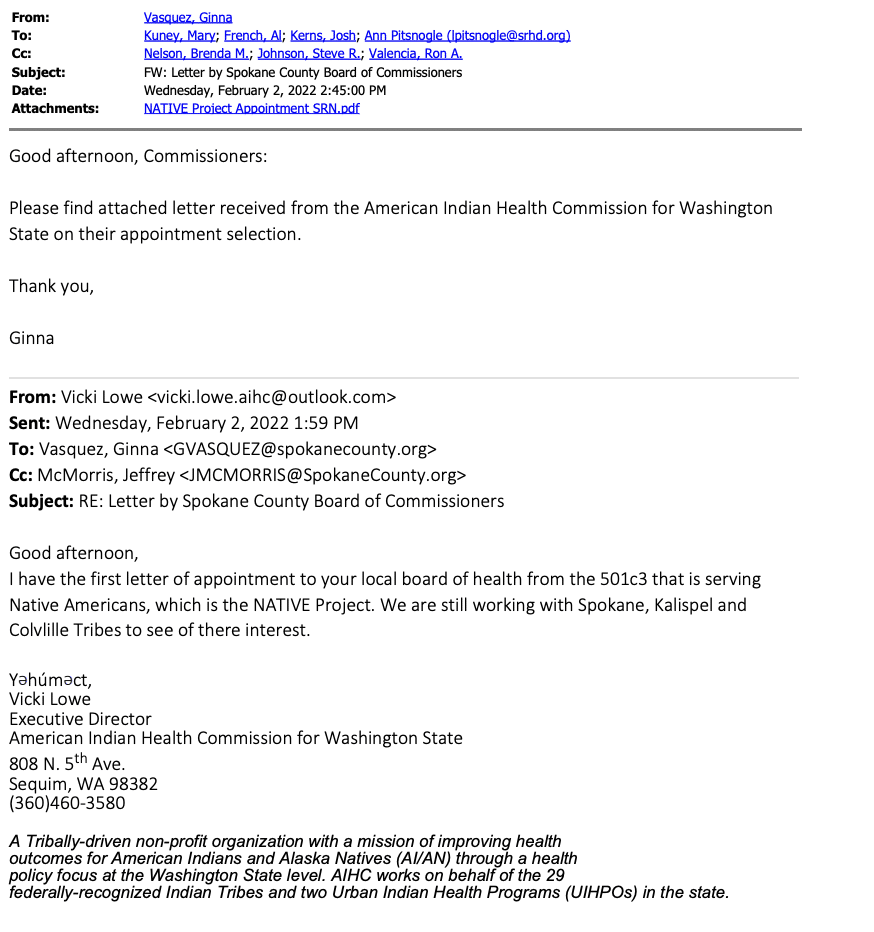

Under Riccelli’s legislation, Dressler’s resolution of support from The NATIVE Project was first sent to the American Indian Health Commission of Washington (AIHCW) for review. Following that, the AIHCW was responsible for sending a candidate recommendation to the Spokane County BOCC, which controls the board appointments to SRHD.

At that point, the commissioners should bring up the candidate for a vote, confirming their appointment to SRHD.

It’s a complicated, acronym-filled process, but one Dressler was willing to navigate.

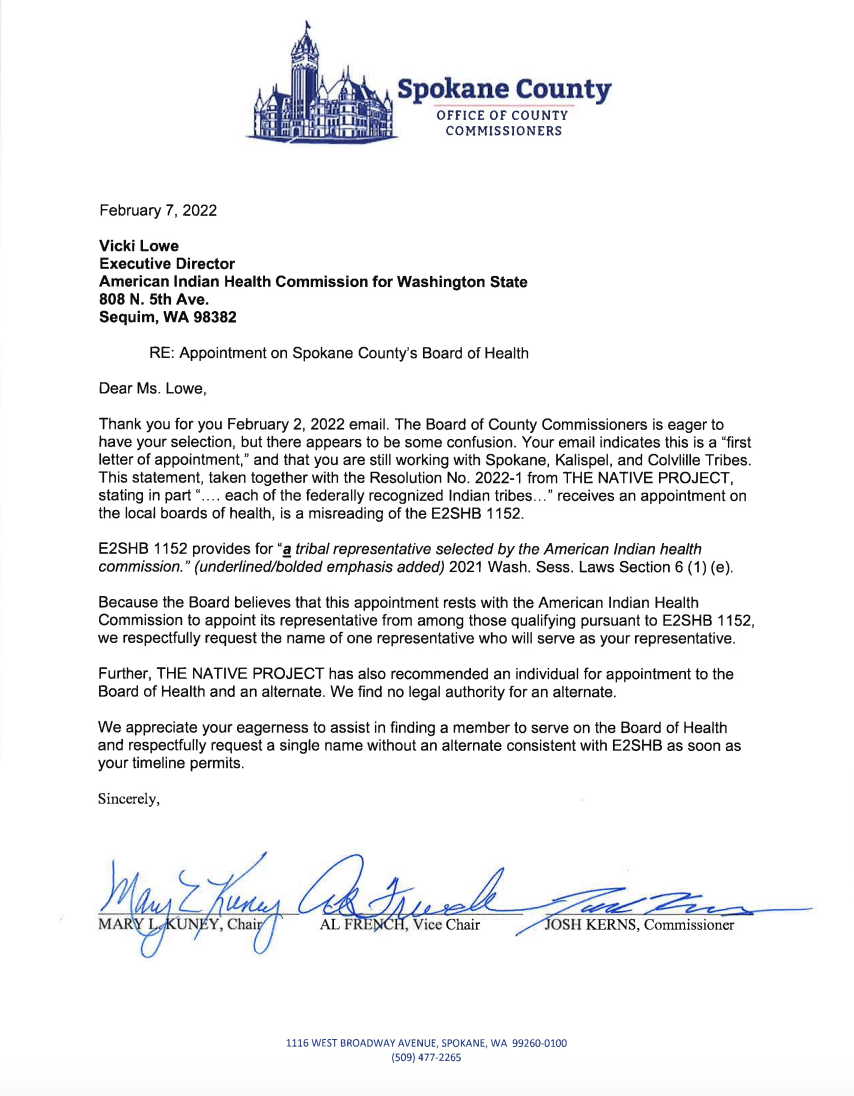

The AIHCW reviewed the resolution of support for Dressler and recommended her to the BOCC on February 2, 2022. The commissioners responded on February 7.

The resolution from The NATIVE Project had recommended Dressler as its delegate, but had also named a second person as an alternate to the board. The BOCC took issue with that, sending a letter to AIHCW requesting that it provide a single name — without an alternate.

While it appears the commissioners are correct that there’s no explicit legal authority in the state law governing these appointments to recommend an alternate, there’s also no legal requirement that a recommendation from AIHCW contain only the recommendation and not an alternate.

RANGE was unable to reach AIHCW for comment despite sending emails and leaving multiple messages, but Dressler said she was under the impression the AIHCW had recommended her as the sole appointment to the board because AIHCW Executive Director Vicki Lowe, who had been communicating with the BOCC, invited Dressler on July 25, 2022 to register for a statewide orientation to new local boards of health members.

According to Dressler, “It was [Lowe’s] understanding at that time that I was on the SRHD board.”

But the BOCC had never even discussed Dressler’s application in a public meeting.

Shortly after that, Dressler said Lowe called to tell her there were issues with the BOCC’s acceptance of her appointment.

“That was the last time I ever heard any more info,” Dressler said.

Because RANGE hasn’t received all of the public records we have requested, it isn’t clear yet how much correspondence between Lowe and Spokane’s BOCC has transpired, but we know that, as recently as March 11, 2024, documents obtained by RANGE indicate that Lowe emailed BOCC Clerk Ginna Vasquez asking, “Is there any change in the state of the Dylan Dressler's appointment? [sic]”

Vasquez responded, “I’m confirming that no email was received from the NATIVE Project for Ms. Dylan Dressler’s application. The last application on file was from July 2020. Once I receive the name of the individual selected by the AIHCW for WA ST. I will forward on the individual’s name to Spokane Regional Health District Board for the Native Health position appointment.”

When RANGE requested all applications to the Tribal Communities position, no documentation about Dressler’s application was provided and the request was closed until we called and inquired specifically about records regarding Dressler, at which point the request was reopened, and we were sent the additional documents we included above, as well as a few emails regarding the applications.

Commissioners Al French and Mary Kuney, who were on the BOCC during the time of Dressler’s original application, could not be reached for comment, but RANGE spoke with Amber Waldref, who replaced French on the SRHD board in January 2023.

Waldref seemed just as confused about the state of the Tribal Communities position as Dressler is.

“Over the last year, I got different stories about if anybody had applied,” Waldref said. “I was originally told [the process] was held up at the American Indian Health Commission, but then I found out that they had sent a name to the BOCC back in 2021. But then that person [Dressler] wasn’t appointed, and I’m not sure why.”

Waldref said she was told by people within the county that there was concern about whether multiple tribes should have a voice on the SRHD board, which prevented an appointment from happening.

When Waldref went digging for more details, she said she ran into the same problems RANGE did.

“I’ve been told about three different things and I’ve had to just do my own research,” Waldref said, “I couldn’t even find [Dressler’s] application. I asked around for it, and it took six months to be able to track down that she did apply and find the application.”

Waldref also found some correspondence between the BOCC and AIHCW, but it didn’t clear anything up for her.

“I’m just not understanding what really happened there, and I can’t tell you because I wasn’t there,” Waldref said. “It's just very confusing.”

Inter-tribal interpretation

County Commissioner Josh Kerns, one of the three commissioners on the SRHD board at the time Dressler’s application was filed, said the reason the Tribal Communities seat remains vacant isn’t confusing at all.

“The American Indian Health Commission for Washington State is the organization in the statute that is designated to make that appointment to the health board,” Kerns said, “They have not done that.”

When Lowe sent the resolution from The NATIVE Project naming Dressler as a delegate, the email stated, “I have the first letter of appointment to your local board of health from the 501c3 that is serving Native Americans, which is the NATIVE Project.”

In an interview with RANGE, Kerns focused on the word “first,” as an indication that the AIHCW was not selecting a sole appointee. “If you say first, that indicates you're planning on sending more,” Kerns said. “You don't get more. You get one.”

It’s unclear if there was additional correspondence between the commissioners to clarify whether “first” was indeed intended to indicate multiple appointees were on their way, but a public records request to the Spokane BOCC asking for all applications turned up none but Dressler’s between Feb 2022 and Feb 2024, so whatever theoretical concern about representation for multiple tribes there may be, only one name had been put forward by the AIHCW: Dressler’s.

“They sent [Dressler’s] name. I think they even sent another name recently, and they have been asked, ‘Is this the person you are appointing?’ And they have indicated they will not appoint one person,” Kerns said. “They want to appoint multiple people. That is not the way the legislation is laid out. They get one appointment and, to date, they have not indicated who that one person is.”

This conflict over interpretation of the statue first surfaced publicly in 2022, when Lowe told The Spokesman that the AIHCW was interpreting the statute to mean that each tribe with reservation and trust lands in the city and each nonprofit serving Indigenous communities should get a seat on the SRHD board, if they wanted it. An email Lowe sent to the commissioners said the NATIVE Project, and the Spokane, Kalispel and Colville tribes would all be eligible to submit someone for appointment.

“Tribes are asked to represent each other all the time, and we know it’s inappropriate but because of the systems that have been put in place it’s either inappropriate representation or none,” Lowe told the paper. She wanted each tribe, and the NATIVE Project, to be able to submit their own representative, and for the commissioners to seat them all, so that no one tribe would be forced to speak for the wants and needs of the other tribes.

It’s unclear if there’s a state body that could clarify disagreements of interpretation like the one between AIHCW’s reading of the law and Kerns’. Riccelli told The Spokesman in 2022 that there might be a need for tweaks to the legislation, “after looking at how implementation goes.” Despite a three-year vacancy on the health board serving Riccelli’s districts, no such tweaks have happened.

Meanwhile, the conservative commissioners have continued to assert their interpretation of the statute: the AIHCW can pick one representative, or they’d continue to leave that seat unfilled.

Waldref, on the other hand, spoke specifically to the conflict of asking one representative to speak on behalf of all tribes.

“I would really like the seat to be filled and I’m hoping we can resolve the concerns about different tribal voices,” she said. “I know this seat comes open every two years, so one thought is we could have different folks sitting on the board and rotating every several years to provide different Native perspectives.”

“I want to see that seat filled,” Waldref said. “I’m hopeful that we have a new application that’s come in and that we can consider that and appoint a person to the board.”

Waldref could soon get her wish.

In her most recent email to the commissioners, Lowe attached a resolution from the Kalispel Tribe, who had appointed Liz Henry as their representative. Lowe did not indicate whether Henry was the sole appointee chosen by AIHCW, and provided some context at the bottom of the email.

“Although other local boards of health have read this and added a set for Tribal representation for each federally recognized Tribe and 502(c)(3) (or Urban Indian Health Organizations); Spokane Regional Health District chose to interpret this from a lack of understanding of what Tribal representation is. One Tribal Nation cannot represent another Tribal Nation, they may only represent themself.

“The other issue was that the District did not accept the NATIVE Project's resolution because it included an alternate and, again, their interpretation was that alternate were not allowed. I don't think that was ever ironed out with the NATIVE Project. I think it is very important to include the voice of both the Kalispel Tribe and the NATIVE Project.

“They both offer health care in a very different way, under some of the same federal laws but mostly different, one is a government, the other and non-profit, both are Indian Health Care Providers. I hope you can understand the difficulties in the assumption that one can represent the other. [sic]”

While Henry was selected as a tribal representative, Dressler’s appointment wasn’t affiliated with a specific tribe but with The NATIVE Project, which is considered an Urban Indian Health Organization.

Still, it is unclear if Henry will be considered for appointment to the board. According to Kerns, it’s not up to the commissioners.

When the AIHCW sends over a single name and says, “This is the one appointee that we have chosen under our authority of the statute,” then, Kerns said, “that person will be appointed to the [SRHD] board.”

Wild, Wild West

When RANGE spoke with Riccelli in late February, he told us the intent of his legislation was to create more balanced and less political health boards in Washington by changing the governing structure, and was inspired, in large part, by things he witnessed in Spokane in the first year of the pandemic.

“The firing of our public health officer in the midst of a pandemic showed that public health professionals and people with lived experience needed a voice [on health boards] and it needs to be a balanced voice with elected politicians,” Riccelli said. In addition to Lutz’ illegal termination, one of the people who actively spread misinformation about masking at a rally organized by Matt Shea was Jason Kinley, a then-sitting SRHD Board Member.

In some ways, Riccelli’s legislation did what he intended.

SRHD no longer has a majority of electeds, and while Riccelli’s legislation allows for counties to seat multiple community stakeholders, Spokane has seated the required minimum of one, currently occupied by Charlie Duranona, a first-generation Cuban-American, disabled veteran and chief of Community Relations for Fairchild Air Force Base.

As for the ways his legislation has failed to achieve his desired results, namely the guaranteed tribal representative, Riccelli doesn't buy the argument made by Kerns that the fault lies in a difference of legal interpretation, or with the American Indian Health Commission of Washington for failing to properly submit an appointee.

He thinks it’s a well-worn tactic from the Al French playbook.

Riccelli cited a previous fight with French that unfolded along similar lines. The Spokane Tribe wanted a vote on the Spokane Regional Transportation Council. French didn’t want to give it to them.

“There's a pattern that is continuing in Al French not moving in a direction to ensure that there’s voices of all our communities, and it seems particularly egregious that tribal representation continues to get caught up in this,” Riccelli said. “At the end of the day, we’ve seen time and time again that Commissioner French has his thumb on a number of these things, and is influencing them in a way that’s not positive for our community.”

As reported by The Inlander in 2019, French’s logic for not seating a tribal representative was largely the same as the reason Kerns gave for not seating Dressler.

“We’ve got multiple tribes that have interests in the county," French told The Inlander at the time. "Do you have one member representing all the tribes or one member representing each tribe? Right now, the council is made up of jurisdictions that are peers. And now you bring in a sovereign nation? How does that change the makeup of the decision process?"

French didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, but Kerns said that while he wasn’t surprised Riccelli would claim a pattern of politicalization, “Marcus can say other people are politicizing things, but Marcus has the track record of politicizing things.”

“Marcus is the one that passed the bill to take away local control in forming the health boards. Marcus was also a part of moving local control away to move the county commission from three to five that added two Democrats,” Kerns said.

While the crux of the disagreement is about which and how many tribal representatives should sit on the SRHD, Dressler herself is an embodiment of how modern Indigenous people carry the roots of many different tribes and traditions, regardless of their enrollment status. “I was born and raised in Spokane & on the Qalispel Indian reservation,” she wrote in a text this week. “I have 3 children indigenous to the Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, Qalispel, Salish Kootenai, Colville, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, Southern Cheyenne, Cree and A’aninin Nations, living on our ancestor’s traditional land. My bloodline and biological successors are genetically related to the health & well-being of this City and the surrounding land, air and waterways.”

And though Dressler still carries her passion for tribal health and advocacy, after two years of frustrated limbo, she isn’t sure she wants to engage with a system that is refusing to engage with her. “It’s very colonial and patriarchal of them to exclude the original peoples,” she said.

Regardless of whether or not the position lands with her, though, she says the need for a tribal member on that board goes beyond representation within a white-dominant system, to what that system can — and in Dressler’s mind, must — learn from Indigenous folkways. “[Public health] does need a community-specific, community-oriented approach,” Dressler said. “That is what is missing in health care and this is what we've been practicing for millennia as Indigenous people.”

For now, the seat remains vacant, and while she hopes for a day where every voice is heard, Spokane isn’t there yet.

“It's the rugged, wild, wild west up in Spokane,” Dressler said. “I think it's important that the public knows that the [SRHD] board does what they want … and nobody cares. Everybody's complicit and complacent and just carrying on, and that indifference and apathy is the killer of all things, and that is where we're at with them.”