By now, it’s no secret that Spokane is in an overdose crisis, and has been for months now. Until this month, however, city officials had no way of knowing just how bad it was, because no one at either the city or county level had ever created a centralized hub to aggregate and parse that data.

Those missing numbers made it hard to make informed decisions about everything from how to organize the front-line response to writing better policies to understanding the scale (beyond “really bad”) to properly budget and allocate resources.

When RANGE went looking, we found pieces of the data puzzle — such as how many people were overdosing, where and when — was spread between local agencies. Those agencies weren’t talking to one another, and no one was aggregating the data that did exist to try to form a complete picture, nor or sharing anything with city officials and policymakers, despite frequent requests for access.

That reporting took weeks of calling agencies and putting together data to move beyond anecdotes and into real numbers. We learned that overdose calls had gone up 30% since 2023. We tracked down an up-to-date death count — 31 between January 1 and February 20 — and information on naloxone usage (the drug used to revive people experiencing an opioid overdose, commonly known as Narcan), which had also gone up.

According to multiple city council members, the article we published on February 23 was the first time they were seeing some of those numbers, and the first time they were all getting on the same page about their goals for data collection.

City Council Member Paul Dillon also said that though he had just joined the council a few months ago, members with a longer-standing tenure, like Michael Cathcart, had been asking for up-to-date overdose data “for a long time,” and never received it.

Dillon also said, once they had the data, it helped he and his colleagues to quickly frame the scale and take action. “I certainly cited the data from that story in subsequent conversations,” said Dillon. “It was a fitting jumping off point for a lot of unity around trying to better our response.”

Service providers and advocates agreed things have gotten better. “Providers saw [overdoses] constantly — multiple, multiple times a day — and they knew it was rampant, but your article helped get it past the anecdotal to the empirical,” said Barry Barfield administrator of the Spokane Homeless Coalition, a group of service providers that meets monthly to strategize about care and exchange resources and ideas. “If you can dig, dig and dig and dig, and get beyond sort of the initial roadblock, you can find data.”

Dillon introduced a draft of a resolution addressing the opioid and overdose crisis that included statistics he’d initially gotten from our article. That resolution — which recently passed — included requests for regional agencies to regularly provide the council with better data.

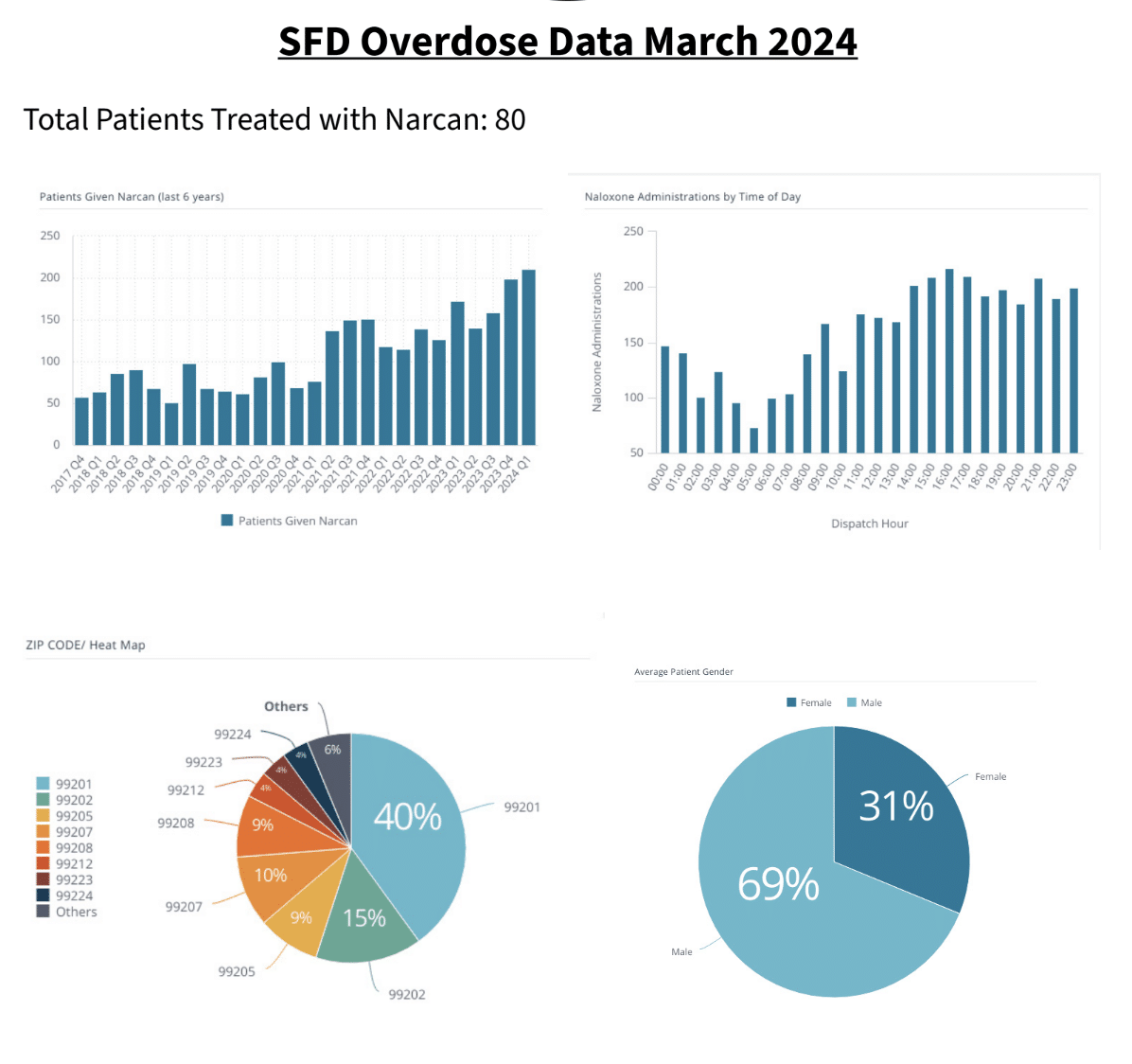

Dillon said it has gotten much easier for council members to access data, especially through city channels. The Spokane Fire Department (SFD) — which had the best data set among the city agencies we reviewed — has started to provide a monthly report to the city council’s Public Safety Committee, which is accessible to the public via that committee’s posted agenda. The data points included the total number of patients treated for overdoses with naloxone, a demographic breakdown of those patients and a heat map showing where those overdoses were happening by zip code.

Up-to-date opioid crisis data courtesy of Spokane Fire Department.

Justin de Ruyter, SFD’s Public Information Officer, said SFD had seen a “noticeable interest in data,” and that they are working to standardize data points for the future.

The Spokane Police Department (SPD) has also started to do more data collection around overdoses — marking dispatch calls with a tag that signifies the caller is reporting a probable overdose. Those tags can then be searched for and the number of results can be collated. The system isn’t perfect: since it happens at the dispatch level, some of the tags might duplicate SFD’s data. There is also a chance that a call that appears to be an overdose might not be, or conversely, officers might respond to a call that hasn’t been tagged, only to discover the person is, in fact, overdosing.

It’s unclear if there’s a protocol to revise those tags at the conclusion of a call, but even with some degree of error, what SPD is currently doing is an improvement over what the agency offered when we initially called in late February, which was purely anecdotal evidence.

When we followed up with SPD’s Lt. Terry Preuninger this week, he said that, though they didn’t have anything to share with RANGE back in late February, they had been collecting those tags since February 8. In that roughly 9 week span, dispatch had tagged 450 calls as potential overdoses.

Preuninger also said the new tagging system was a direct result of increased requests for the information from both media and administrators from both the city and county.

“Even though we, the police department, aren't the caretakers of all of the medical stuff, we have more resources dedicated to collecting information,” Preuninger said. He said internally, the push for data came from a police lieutenant who supervises the dispatch center. “[The lieutenant] said, ‘We’ve gotta start capturing this. People are asking and we’re not able to give them an accurate number. Let’s come up with at least something, even if it’s rudimentary, to get an idea.’”

It’s not clear if that data will also start to appear in SPD’s regular briefings to Spokane City Council’s Public Safety Committee, but it is being collected now.

Beyond increasing elected officials’ access to key data, we also saw other citywide impacts of our reporting:

- Dillon invited Dr. Bob Lutz to share statewide overdose data with the Spokane City Council. The presentation was open to the public which included regional numbers that were more up-to-date than data provided to the council by the Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD). (Shortly after Lutz gave that presentation, he also resigned from the State Department of Health.)

- The Spokane Homeless Coalition invited RANGE, Lutz and a few service providers to sit on a panel about current data collection practices and answer questions about the current state of the overdose and opioid crisis.

- Multiple citizens cited RANGE’s reporting while delivering public testimony in support of Dillon’s resolution, which ultimately passed.

- Due to Dillon’s resolution, the city council hosted a community conversation focused on the opioid and overdose epidemic, where healthcare professionals, service providers and people with lived experience answered questions from the public and city officials on the overdose crisis.

We’re proud to see how thorough reporting can inform and inspire meaningful change in our community, but there’s more work to be done. Dillon said that while many city agencies have opened up their books to the council, SRHD has been less cooperative.

“They still have not listed overdoses as a notifiable condition,” Dillon said. “They still have not updated their dashboard with 2023 data or even the month-to-month real time data that we were requesting they do.”

He hopes that as city officials continue to push for more accurate data, that will change.

“We might have different ideas about how to get there,” Dillon said, “but we don't want to see people die in our community.”