The day Vanessa Delgado was fired, she led an hours-long, all-staff meeting to plan all of the Pride and Multicultural Centers’ programming for the next academic year.

It ended with a surprise 15-minute meeting and an HR escort to pack up her desk.

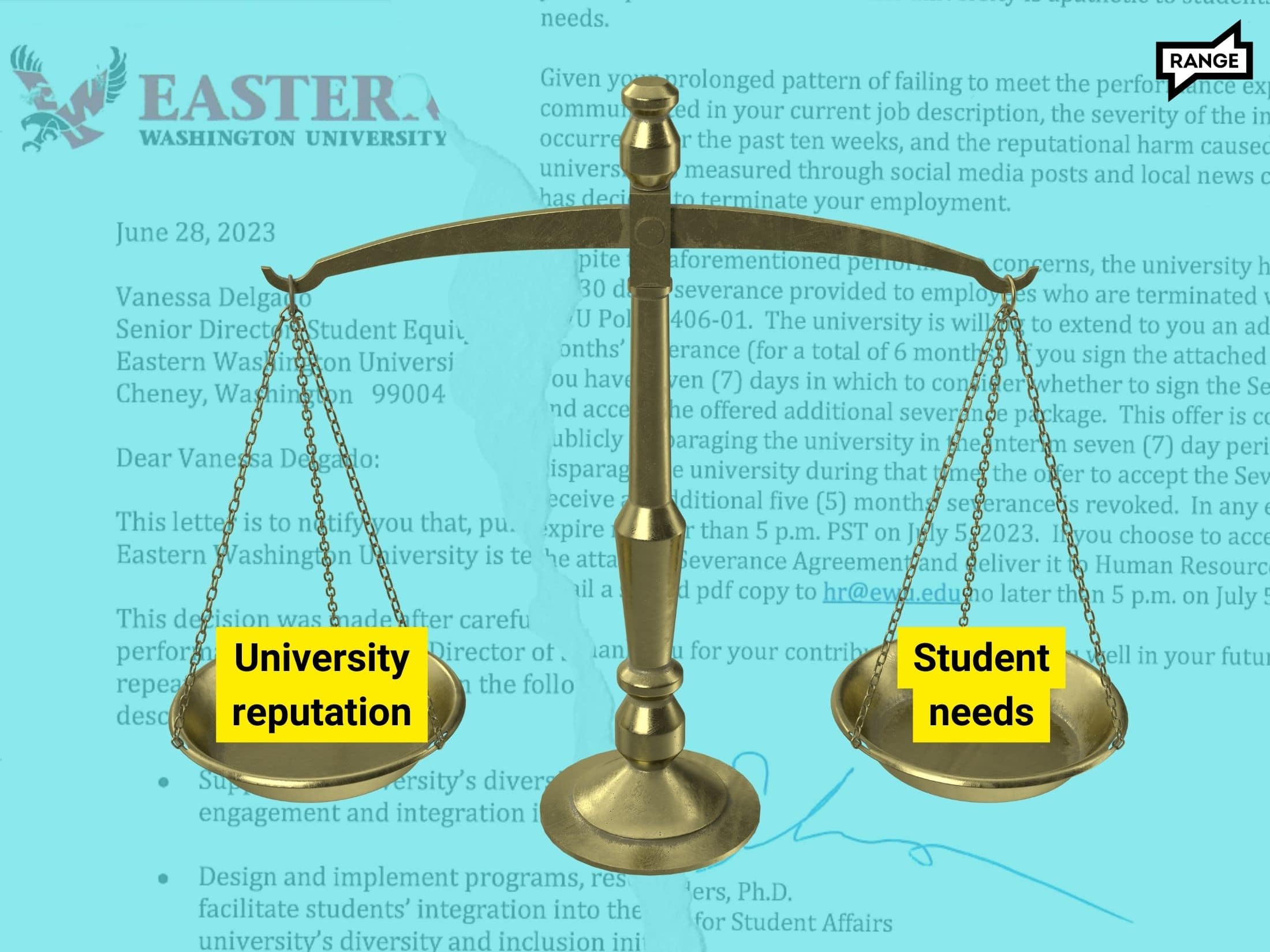

The termination letter Delgado received at that meeting paints a picture of a higher-level administration employee actively involved in undermining students’ faith and trust in Eastern Washington University (EWU). It’s a portrait painted at length, unfolding over three scathing pages.

“Your job as the senior director of Student Equity and Inclusion is to support and help integrate students, not incite feelings of discontent, exclusion, and otherness by promoting a negative narrative that the university’s efforts are inadequate, or that the university does not care about the very students your Centers were designed to support,” the letter reads, in part.

The unredacted letter, which RANGE obtained through a public records request, was written by former Vice President of Student Affairs Rob Sauders, who left his position within days of terminating Delgado. The letter also accuses Delgado of openly disparaging the university's diversity and inclusion initiatives, criticizing the university's support for the Centers and her programs and denigrating the university's support for her programs at an Alumni Board meeting.

To back up these claims, Sauders cites his experiences and the experiences of other unnamed “prior supervisors and other university administrators.”

RANGE has not yet received all of the documents we requested, and performance evaluations are redacted by state law, but the termination letter appears to be the first written reprimand Delgado had received since joining the university in 2018.

Everything we have reviewed up to this point paints the picture of a young professional rising quickly through leadership. After joining EWU as director of the Multicultural center in 2018, Delgado was recommended for promotion by Sauders himself three times in 2021, rising to senior director of the university’s student equity and inclusion initiatives in a six-month span.

Delgado’s fall came just as quickly. Everything the letter accuses Delgado of happened “over the past three months,” Sauders writes, meaning April, May and June of 2023.

Those three months were a tumultuous time on campus, as the university saw high-profile incidents of slurs targeting Black and queer students written in spaces billed as safe — a dance studio used by Eastern’s Black Student Union (BSU) in the first case; the gender neutral floor of a dorm building in the second — as well as the repeated presence of a street preacher yelling slurs into a bullhorn outside the Pence Union Building, which houses the Pride and Multicultural Centers.

Despite the impacted students RANGE talked to consistently citing Delgado and the Centers as a bastion of safety they could turn to during the crises, Sauders’ letter claimed a key reason for her termination was a failure to “properly represent the university or to adequately perform [her] duties as part of the university administration,” during these events.

When RANGE shared the letter with Sierra Alexander, former graduate student assistant in the Multicultural Center and former president of Eastern’s BSU, this language struck her as odd. “They said she failed to integrate students into university campus life,” Alexander said, “We repeatedly told the administration, while I was BSU president, that we felt supported by Vanessa and the Centers, and that that was the only place in the university we felt supported.”

Alexander’s perspective appears to have been part of the problem for Sauders and the rest of the senior leadership: They felt Delgado’s allegiances were too much with the protesting students, and not enough with the university and senior administration.

“Your job as the Senior Director of Student Equity and Inclusion is to support and help integrate students, not incite feelings of discontent, exclusion, and otherness by promoting a negative narrative that the university's efforts are inadequate or that the university does not care about the very students your Centers were designed to support,” the letter reads.

In the mind of Sauders and his colleagues, the existence of the Centers should have been evidence of the university’s commitment to queer and students of color, regardless of the larger university response to hate incidents like the ones RANGE has previously chronicled in depth.

Delgado was supposed to support the students and support the rest of the administration, but when those two came into prolonged conflict, administrators told Delgado, “Rather than understanding your role as one that is collaborative, supporting the students and university alike, you speak with the university's voice but work as an adversary to the very organization of which you are a part.”

As they were firing her, Sauders and the senior administration he was writing on behalf of told Delgado her job was to ensure students viewed the university as safe and inclusive because they had created the centers Delgado oversaw. They accused her of instead encouraging students to fight for changes to broader university policy outside of the centers, and they accused Delgado of disparaging those broader university responses in public, citing “reputational harm caused by your actions to the university as measured through social media posts and local news coverage.”

The letter doesn’t cite events with enough specificity that RANGE could verify the claims of reputational harm, but Delgado was not quoted in any news reports about the hate incidents. Scouring her social media, there’s no evidence that she ever disparaged the university or publicly supported the viral social media posts circulated by student clubs, though those posts could have been deleted. Students told RANGE Delgado went out of her way to distance herself from any connection or support of their social media efforts.

Sasha Sharman, a former Eagle Pride member and dual-enrollment student at Eastern, was involved in the June social media campaign from Eagle Pride and other queer students. They said that the blame shouldn’t fall on Delgado’s shoulders, and drew a clear distinction between the support they received at the Centers and the lack of care they felt from the administrators.

“The administrators were failing to support us. Part of the goal there was reputational harm, because nothing else was getting through.”

Alexander, who spoke on behalf of BSU with local news outlets and led the social media campaign in April calling for administrative support after a racist slur was graffitied onto a BSU dance practice space, was particularly affronted by the termination’s claim that Delgado was responsible for any reputational harm caused by the club’s campaign.

“The thing is, they have no idea that we would’ve done something way more drastic, like a sit-in or picketing,” she said. “Vanessa was the one that de-escalated the situation. Had it not been for Vanessa being there, it would’ve been a hundred times worse.”

Madelyn Roy, who worked in the Multicultural Center as the Student Equity & Belonging Coordinator until their resignation in September, said that Delgado did as much as she could to ease student anger.

“I don't think [the administration] realized how much Vanessa and the team talked people down,” Roy said. “And what some of the students wanted to do versus compromising with the social media posts, there [were] much grander plans in place that we were able to kind of help prevent on behalf of the university.”

Dr. Nick Franco, Vanessa’s direct supervisor at the time, was on vacation when she was fired. A statement provided to RANGE by Franco’s lawyer contends Franco was kept completely out of the loop about Delgado’s termination.

“Dr. Franco was not made aware of any terminable offenses prior to Ms. Delgado’s termination. They are not aware of any “repeated failures to perform” and do not agree with the specific findings set forth in Ms. Delgado's termination letter,” the statement reads, “Dr. Franco found Ms. Delgado to be a supportive director who was active and involved across campus, not just at the Multicultural and Pride Centers, and was always open and receptive to feedback.”

Franco has resigned their Associate Vice President position with the university since our first story came out, but will continue in an adjunct professor role.

Besides Franco, Delgado had two other former supervisors: Dr. Shari Clarke, who declined to comment, and Rob Sauders, who signed the termination letter.

Many of the accusations are vague, or general. Only one time does Sauders identify a specific event where Delgado disparaged the university’s DEI initiatives — a meeting of the alumni board — but even then, there was no reference to which date. Those board meetings are not public, and RANGE could not find recordings of the meetings, if any exist. We reached out to EWU’s Office of Alumni Relations to see if we could get clarity or to corroborate these accusations, but received no call back. Dave Meany, spokesman for the university, said “whatever information is in the public records you obtained is all the university can provide about her employment.’

We also reached out to Sauders, who has returned to his original role as a Professor of Geography, but he directed us back to Meany.

Delgado has never responded to any of RANGE’s requests for comment, and the termination letter gives a likely reason why. Despite three pages of brutal feedback on her performance, Sauders said they were terminating her without cause, and offered her six months paid severance (a sum of roughly $45,000, according to her personnel file) if she signed a non-disparagement agreement preventing her from further critiquing the university.

And while Delgado isn’t talking, her former colleagues and mentees are.

Roy said Delgado’s termination was “upsetting and honestly traumatizing because it was so unexpected,” and that the letter was an unfair reflection of Delgado’s job performance.

“The fact that they said she failed to support university diversity and inclusion initiatives and facilitate student engagement is wild to me,” Roy said. “She was probably the best out of any of us in engaging with students and building rapport. She was the reason that a lot of the students in those centers were at Eastern and willing to engage at Eastern.”

When we showed the letter to Zoe Swenson, a student employee in the Pride Center, and asked if this letter seemed like an accurate account of Vanessa’s behavior in those three months, she said, “I do not think so, no. No. Absolutely not. No.”

Jocelyn, a former Student Affairs employee who asked to be identified by first name only, was supervised by Delgado from mid-2021 to the end of 2022. Though Jocelyn no longer worked in Student Affairs during the period covering Delgado’s firing, she said that no part of the behavior in the termination letter aligned with her experience of Delgado.

“Her praises have always been sung around. Her inclusionary practices and her willingness to be proactive in communicating with our students at the time,” Jocelyn said, “So when I see the bullets that say that there was a failure to design and implement programs or resources, that's just not true. And the failure to facilitate creation of affirming and supportive environments — not true either.”

Alexander described the letter as “contradictory, retaliatory and really unfair.” She said she doesn’t understand how the administration could claim Delgado didn’t support diversity and inclusion incentives or facilitate the creation of an affirming and supportive environment when retention rates for students of color, a key part of university DEI goals, seemed to rest almost exclusively on Delgado’s shoulders.

“She was making sure that everybody felt safe,” Alexander said. “She was keeping [students] from leaving the school.”

Delgado’s former coworkers and supervisors didn’t recognize her in the termination letter and neither did the students she served.

Kai Reiner, president of Queers in STEM, a club at the university, told us, “When I first got sent that letter and read through it, I was at my partner's birthday party and I had to take 45 minutes to just walk around because of how frustrating it was — because of how inaccurate it was.”

Reiner had been one of five students able to attend a meeting held by President Shari McMahan and her executive leadership team on the last day of the quarter. RANGE reviewed notes from that meeting, which show student complaints centered around facing misgendering, homophobia and microaggressions in their classrooms, work-study jobs and dorms — all spaces Delgado and the Centers had no power to influence.

Having attended the meeting, and then reading the termination letter, Reiner said they were horrified to see fragments of complaints they’d raised specifically about executive leadership being used against Delgado in the termination letter.

“It felt like they weren’t taking it seriously. And that they never intended to take those complaints seriously,” Reiner said. “I was fearful because now it feels like if we speak up and address issues, that we will also have to worry about the job safety of those who care for us.”

Yet, Sauders’ language in the termination letter puts the blame for these student frustrations at Delgado’s feet, stating “Students report feeling supported by the Multicultural and Pride Centers, but report feeling unsupported by the university. This is a contradiction - the Multicultural and Pride Centers are the university, and the support provided by the Centers is a reflection of the university's support for its students … This reflects a fundamental failure in your leadership of those entities.”

Reiner wasn’t the only student to take issue with this characterization. Swenson called it “a cop out to shift blame onto the centers.” Sharman, the former Eagle Pride member and dual-enrollment student, noted it as deeply unfair to task Delgado with ensuring that not only the spaces she managed, but also the entire campus was safe and supportive.

“While the Multicultural Center and Pride Center are great places to find community and explore your own identity, they don't have the authority nor the purview to affect the everyday,” said Sharman. “The infrastructure on campus, the removal of gender inclusive bathrooms, the way teachers misgender us in class, the way curriculum is non-inclusive … the scope of the Multicultural Center simply isn't large enough to accommodate all of the struggles that students are having on campus.”

Both Sharman and Reiner were disheartened by what they saw as a university administration trying to get rid of student complaints by pinning them all to the collar of a beloved employee and firing her for them.

It’s a moot point for Sharman, who will be attending a larger, more resourced university in the fall, but Reiner and Zoe Swenson feel it will be hard for the university administration to rebuild trust with queer and BIPOC students.

“It feels like they've done too much damage. We lost a huge part of our staff that supported us,” said Reiner. “Acknowledging that they were in the wrong would help, because from what I've seen so far, it has been a continuation of the university executive administration trying to save face to the public while silencing students and staff here.”

“They've already done so much damage in such a short amount of time,” Swenson said, “you took all of these support systems out and I feel like everybody’s going to be on edge no matter what.”

Swenson also isn’t sure any show of administrative support at this point would feel genuine.

“They're just trying to cover their asses and be like ‘quick, let's try to support these minority students,’ but we wanted that last year,” she said, “Now that you've fired Vanessa and now that Nick Franco's gone and now that all of these people are leaving, that's not what we want. Why couldn't you have [supported us] a year ago when we wanted you to?”

Why Eastern?

This is the second of what is quickly becoming a series of stories about Eastern Washington University, so it’s natural to ask: why focus on them when we haven’t done much higher education reporting before? Eastern is often overshadowed by other area schools, but it’s hard to overstate its impact on our local workforce and people’s lives. The school markets itself as “Spokane’s Public University” — and that’s true.

It’s especially true for poor and diverse students. Eastern has one of the lowest in-state tuition of any public university in Washington, dual enrollment programs and transfer agreements with local community colleges. It’s an institution that appears to pride itself on its accessibility, and markets itself to students who may find themselves excluded from other institutions. It says it wants to be the home of the first-generation students, BIPOC students and queer students of our region.

For Spokane to become a more just and equitable place, we need Eastern to thrive, and make good on those aspirations. It's our job as journalists to hold it accountable to the promises it makes to its students, its employees and we as taxpayers. — the editors