Update:

On Monday night, city council voted to adopt a 66% increase in fees as proposed by council member Bingle. Those fees will be in place until March 4, 2024 when the city will either adopt the fees proposed two weeks ago or come up with a new plan. This article from Emry Dinman in The Spokesman-Review follows last night's haggling over the fees.When Spokane City Council passed new ordinances increasing development fees on March 13, the response from local developers was swift and clear. They claimed the new fees would kill the construction of thousands of housing units amidst an already desperate housing crisis.

The fees hadn’t been raised in more than 20 years, and the proposed structure was made by the city’s engineering department and ratified by the council, with Council President Breean Beggs saying, effectively, that this city council needed to do what other councils have been putting off for two decades: bring fees closer in line with the growth goals of city leaders and the rapidly increasing costs of construction.

The two ordinances retool what the city charges developers for Transportation Impact Fees and General Facilities Charges citywide. Both are one-time fees for new development, though what they pay for and when the developer must pay varies.

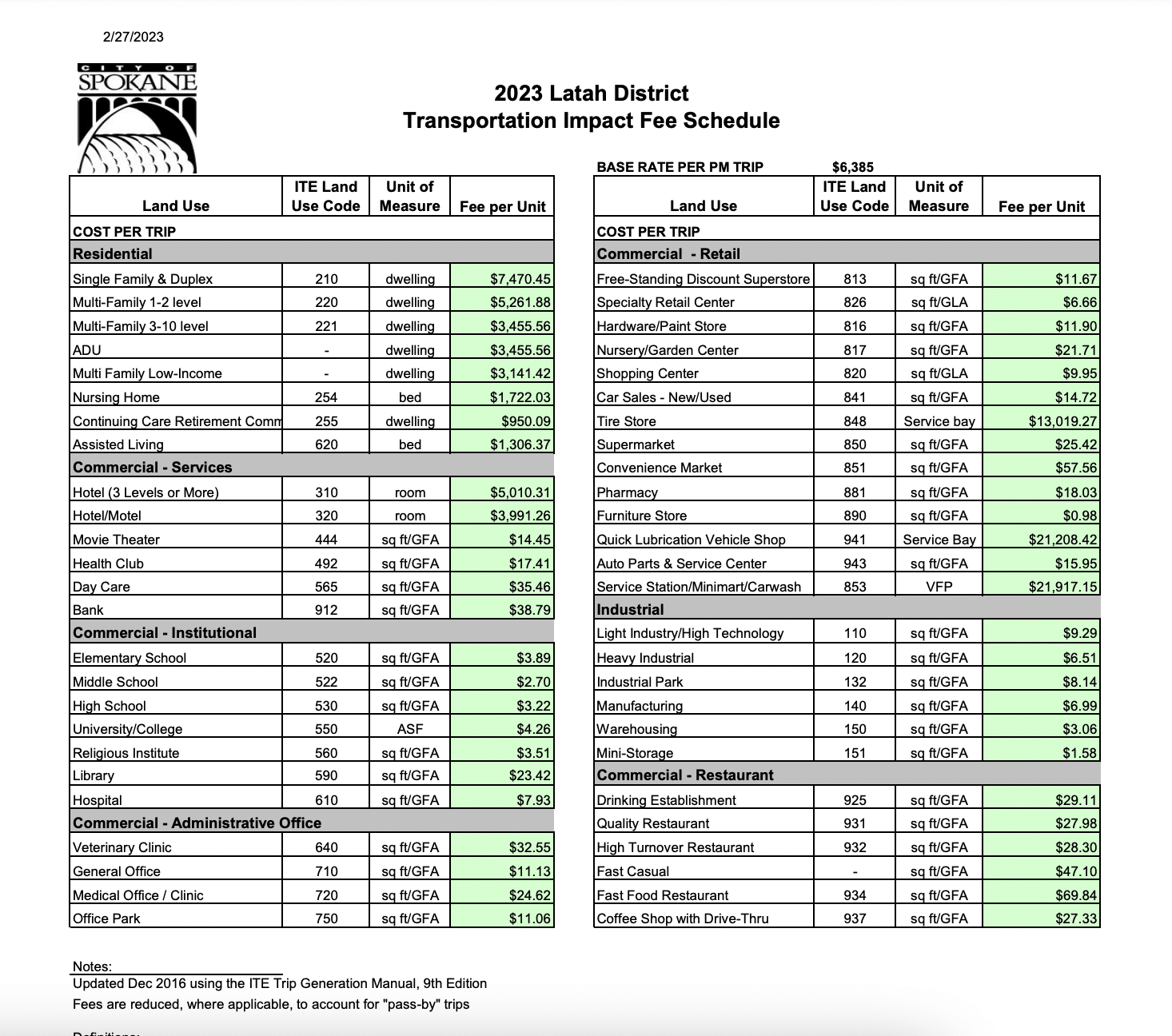

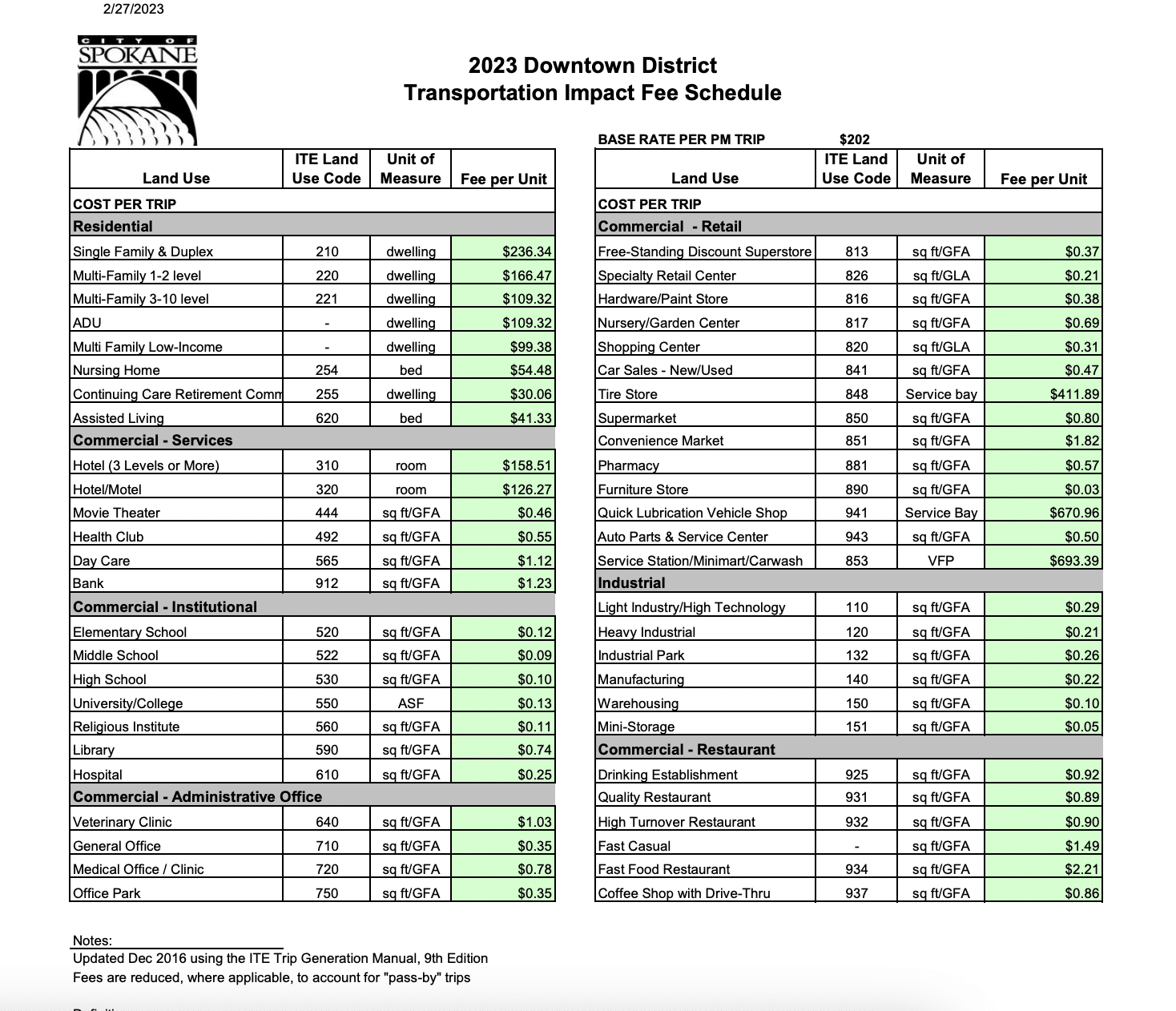

Transportation Impact Fees vary depending on what area of the city the development is located in, what type of structure is being built, and the size of the structure or dwellings. They go into a fund that pays for publicly-owned streets and roads, sidewalks, and streetscapes that are created by new developments. These fees must be paid early in the development cycle, during the permitting process, and under RCW 82.02.050, impact fees can not be used to maintain or repair existing infrastructure.

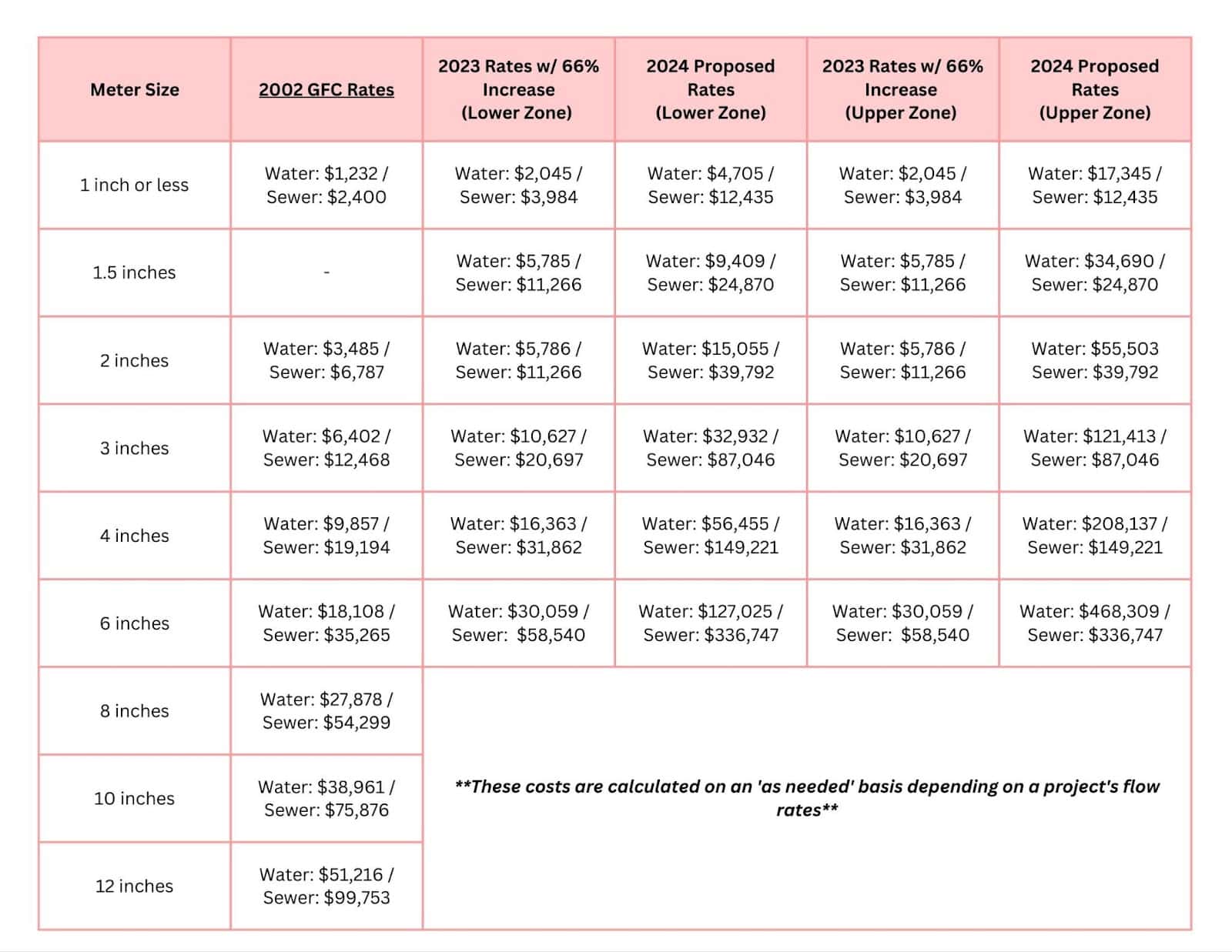

General Facilities Charges (GFCs) are charged to developers and scale in cost depending on where the project is located (upper elevations versus lower elevations) and the size of the water meter. Like impact fees, GFCs are considered a contribution toward funding the city’s capital projects that add additional capacity to water and wastewater systems. GFCs are paid later in the process — either at the time of connecting or applying to connect to city water and sewer systems and explicitly cannot be used for maintenance.

Prior to passing the recent ordinances, GFC rates were based on infrastructure costs that were calculated in 2002 and impact fees were last updated in 2019. Councilmembers pushed for the increase on the rationale that the cost of labor and materials has gone up significantly in 20 years while the GFC rates have stayed the same.

“It’s a political football, and as we’ve seen for the last 20 years, both mayors and councilmembers have been like ‘not this year, we could go another year and not do it,’ and now we have to pay the price,” Beggs said. “It’s disruptive, and those who bet that the council and the mayor would yet again not raise (development fees) lost that bet.”

When the new rates were announced, developers bashed the changes and said they would result in thousands of canceled projects during an ongoing regional housing crisis. Now, the council appears poised to strike a middle ground that makes a small increase now and pushes off implementing the full fees later in a bid to get more work done this year while cementing the new changes beginning in 2024.

Measuring the impact of Impact Fees

According to the Spokane Realtors Association and the Spokane Homebuilder’s Association, developers feel the fee increases are too extreme and would greatly impact a developer’s ability to complete and profit from their projects, meaning fewer homes would be built during perhaps the tightest housing market Spokane has ever seen.

A day after the council passed the ordinances, the two associations issued a survey of unnamed developers claiming the changes would mean more than 2,000 construction projects would be canceled. Representatives from both associations spoke with RANGE but declined to say where that 2,000+ figure comes from, whether it was self-reported by the surveyed developers, and whether they made an effort to independently verify those numbers.

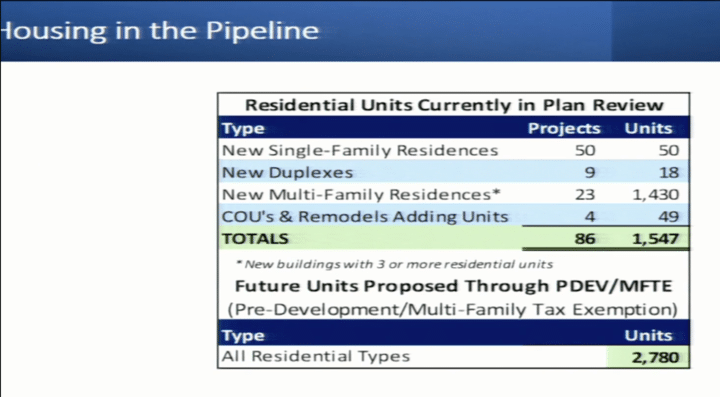

According to a March 13 presentation by Steve McDonald, Spokane’s director of community and economic development, there do not appear to be anywhere near 2,000 housing projects in the city’s housing pipeline. There are currently 86 residential projects in plan review, totaling 1,547 units. There are an additional 2,780 units — not projects — in the pre-development process.

“Spokane City Council members, last night, effectively caused this shutdown — in the middle of a housing crisis — in order to fund new projects they want [to build],” the survey press release reads.

Looking at the impact fees and GFC schedules, the price developers pay for their portion of the impact on the city’s infrastructure greatly depends on the type of building being constructed, where it’s located, and what combination of water and sewer sizes the construction needs to meet the water flow requirements. Typically, single-family homes use the smallest meter sizes (one inch or less) and larger projects use larger meter sizes (two inches or more).

The Realtors and Home Builders estimated “new housing will cost an additional $19,000 to $32,000 per new house for water/sewer hookups and transportation fees,” but it’s not clear how they arrived at those numbers, and the actual fees vary widely depending on the area of town the building takes place.

In the Latah District, for example, transportation impact fees for new single-family homes and duplexes would cost about $7,470. The same type of dwelling in the “Downtown” district (which also includes much of the South Hill north of 29th), however, would only cost $236.

When these impact fees were originally created and codified, lawmakers said the intent was to ensure new developments were paying a proportionate share of the cost caused by new traffic and transit demand. Whether those exact fees are reasonable or not, the greater expense in a less-developed, further-flung area like Latah Valley and the relatively cheaper cost for the completely built-up lower South Hill is in keeping with the statute as written.

General facilities charges are a lot more complex, but by ordinance, they are intended to serve a similar purpose: to incentivize building closer in and to put more of the burden of extending services like water and sewer to under-developed areas on the developers choosing to develop that far out. The ordinance reads, in part: “General facilities charges are intended to defray costs created by new system demand, such as costs of providing increased system capacity for new or increased demand and other capital costs associated with new connections and equitable share of the cost of the system.” The law later clarifies that the funds are used to finance impacts to the system created by new growth and new customers.

Neither the Spokane Association of Realtors representative nor the Spokane Homebuilder’s Association representative debated the need for these fees to fund the building of critical infrastructure at their projects but they were concerned with how steep the increases were and how quickly they were being implemented. “They’re saying that these builders and developers need to pay their fair share, but the builders and developers that are building today are not the problem,” Spokane Association of Realtors President Tom Hormell said. “I’ve even heard one of the council members, in a response to us, say something about how the builders and developers have been taking advantage of the city for years, and my question is how is it taking advantage when they’re paying the fee that you currently charge?”

The realtors and home builders say their survey included over 100 developers and asked how the fees would impact the city’s housing market. While the release doesn’t specify how many developers responded to the poll, Spokane Homebuilder’s Association Governmental Affairs Director Jennifer Thomas told RANGE that just 50 of the developers who were sent the survey reported back.

Among those who did respond, 89% said rate hikes would be “extremely harmful.” Almost 74% reported they would have to “stop projects in development immediately,” in response to the hikes. About 84% of respondents reported being involved in 50 projects or less.

Most developers favored Spokane City Council District 1 Councilman Jonathan Bingle’s alternative proposal. Under Bingle’s plan, the city would immediately increase the 2002 GFC rates by 66% for an interim amount of time while the council “defines a public engagement process … to update the fee schedule and establish a corresponding infrastructure plan to match.” Bingle’s plan identifies the 66% increase as the equivalent of consumer price index increases since 2002. The consumer price index is just one measure of inflation.

Charting a Path Forward

After nearly two hours of public testimony from Spokane’s construction and development community and members of Citizen Action for Latah Valley group, the Spokane City Council voted to pass the ordinances on March 13 and discussed suspending its rules at the March 27 meeting to debate and make substitutions to address the concerns of some council members and developers.

Beggs told RANGE that he and Councilmember Lori Kinnear plan to propose two small tweaks to the General Facilities Charges to encourage housing development while also collecting more funding for transportation infrastructure and public facilities projects.

Under the new proposal, which marries the initial ordinance and portions of Bingle’s proposal, General Facilities Charges would increase by 66% on top of the rates established in 2002 for the remainder of 2023. The charges would then increase to the rates approved at the March 13 city council meeting at the beginning of 2024 and apply to all newly permitted construction projects. All rate increases after 2024 will be adjusted by using a 5-year average of the Engineering News-Record Construction Costs Index — an industry-standard measure of construction inflation — according to the appendix filed with the Spokane City Council for the March 27 meeting.

Putting off the approved rate changes until 2024 means that any rate changes will be subject to the whims of the city council, council president and mayoral elections in November 2023. That creates a huge incentive for developers, who are already the highest-spending interest group in political campaigns in Spokane, to continue to spend on campaigns in the hope that a more conservative council would overturn the rate increases.

“We’re giving (developers) a chance to get their projects built this year, but for the people in the future, (we’re) saying “we’ve changed the rules, and we don’t want to you build houses out in the fringes of the city where it’s super expensive to hook up sewer, and water, and streets,” Council President Beggs said. “We want you to build in infill, and we want you to fill up empty lots or tear down one house on a large lot and put four…under the rules that we have now, that’s where all these incentives are.”

One Western Washington property developer new to the Spokane market who didn’t want to be identified by name offered to share the estimated costs to build their four-plex project. The property set for development is located in an upper elevation on Spokane’s South Hill and was purchased for approximately $300,000. The developer plans to put $700,000 into tearing down a single-family home and building the new four-unit property. According to pre-construction estimates by the project’s engineer, the property will require a two-inch water meter and a six-inch wastewater meter.

Under the 2002 GFCs schedule, the developer would pay $38,750 to connect to the city’s water and sewer lines. After the new rates were passed, those same hookups would cost $391,250. That’s a 910% increase in GFC fees. The developer told RANGE they’ll likely have to cut the amount of money they were planning to spend on amenities and upgrades and increase what they’ll charge to rent the four units (one of which is designated as an affordable unit) to recoup costs.

Despite the increase, the developer said the project would continue, but they would likely need to move the construction start date from July to later in the year or into next year if they’re charged the 2024 rates.

So where does this leave Spokane’s housing market? Only time will tell whether the increased fees truly shut down enough projects to make Spokane’s already tight housing market worse off. While developers certainly think so, Council President Beggs disagrees.

“There’s a huge demand in Spokane for housing, and housing is based on demand, not on the cost of building it,” Beggs said. “The market is strong and prices have more than doubled in the last few years, and (developers) will keep building. They might build in different places and they may build differently…but they will keep building because there’s a market for it.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect that impact fees were last updated in 2019, while only GFCs have not been updated since 2002.

Another way to help us out is to forward this article to a friend and encourage them to sign up for our newsletter.