When the Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD) began a feasibility study back in May to determine if privatizing the district’s Treatment Services Division was A.) better for the community and B.) even possible, the woman guiding the work, SRHD Administrator Dr. Alicia Thompson, sat down with RANGE to describe the process that would ultimately inform the Spokane County Board of Health’s decisions.

Thompson told RANGE she and the staff had been careful to design a three-step study that would center the needs of vulnerable people with the most to lose — the roughly 1,000 patients who rely on the Treatment Services Division’s Opioid Treatment Program. As of now, the study is nearing the end of step one.

The program in question helps people manage opioid addiction and withdrawal symptoms via methadone prescriptions and mental health services, and is the largest of only two similar programs in Washington run by local health districts (the other is Tacoma).

So SRHD’s program is unique, and doesn’t have many peers to look to for comparison. It has also been running since 1990 and is a deeply woven part of both Spokane’s mental health framework, its recovery framework, and — as our housing crisis has grown — an increasingly vital piece of Spokane’s homelessness response.

At the RANGE interview with Thompson were April Pinckney, Associate Director of Treatment Services and Kelli Hawkins, the Director of Public Information and Government Affairs. In different ways, Thompson and Pinckney talked about how delicate recovery can be. Patients become extremely attached to the counselors and caseworkers, who stick with each patient throughout recovery. Changing a trusted staff member can harm a person’s recovery. Even discussing the possibility of change can too.

“One of my biggest fears in this whole process is the potential harm to clients because of the unknown this process is introducing,” Thompson told RANGE. She didn’t want current patients to fear that they could lose access to the treatment that enabled them to work, to parent, to function.

Unfortunately, despite Thompson and SRHD staff’s care during the process, one local advocate believes Thompson’s fears have been realized.

Though Thompson is leading the study, the ultimate decision lies with the Spokane County Board of Health, and at July’s board meeting, several members made comments suggesting they would be in favor of moving the process along to step two before step one was completed.

These comments sent up red flags for people involved in the process. After that meeting, hadley morrow (who does not capitalize their name and asked us not to as well), a private consultant who worked with the health district to facilitate community listening sessions and surveys told RANGE that community members and employees shared worries that the Board may ignore Thompson’s process — and the voice of the community — entirely, in favor of rushing towards privatization.

RANGE helped plan a town hall community listening session with morrow to better understand the feelings of community members who might be impacted.

In addition to morrow’s role convening the town hall, SRHD staff conducting the internal patient survey had asked to share morrow’s contact info with patients who did not feel comfortable sharing their opinions directly with SRHD, for fear of putting their access to services in jeopardy.

Shortly after their number was passed along, morrow said they received phone calls from multiple patients who said they were experiencing suicidal ideation because of the Feasibility Study.

The process, the meeting, the comments

Thompson’s carefully designed process officially began in May, after her proposal was approved at the April BOH meeting. The study, which is outlined in depth here, seeks to determine if privatizing the district’s Treatment Services Division was a good idea.

The study is divided into three phases, with a few questions Thompson would research and answer. At the end of each phase, Thompson will present her recommendation to SRHD’s Board of Health on whether or not the feasibility study should continue, or if separation is infeasible. Then, a vote from the BOH would be required to advance the study to the next phase, using a decision-making matrix created by Thompson.

Phase 1 of the study sought to determine whether a privatization of the Treatment Services Division — which manages both mental health services and the state’s largest Opioid Treatment Program to help patients manage opioid addiction and withdrawal symptoms with methadone prescriptions — would be better for the community, and whether any private healthcare companies even had the interest and ability to take the division on.

The division serves over 1,000 clients, has around 60 employees and has been profitable for all but two years in recent memory — 2013 and 2023 — and the majority of years since it began, but Thompson told RANGE there had been concerns about the cost to the taxpayers during “bad years,” and the structural barriers to expansion.

In phase one, Thompson and her team have conducted surveys of employees, patients and other stakeholders, hosted SRHD-branded town halls, analyzed financial, operational and performance data and held informal meetings with private opioid treatment programs to gauge interest and ability to take the program on. Thompson also worked with morrow to reach additional community members, who shared their thoughts during listening sessions and surveys facilitated by morrow, which were then submitted in a report to Thompson on August 16.

On September 26, Thompson is scheduled to give her first recommendation on whether or not to continue the process, which the BOH would immediately vote on. If Thompson were to recommend moving to phase two and the board votes to do so, Thompson would begin the complex process of assessing the regulatory hurdles of privatizing a public health service, analyzing the financial situation of the division, estimating its market value and creating a website with a draft separation plan and timeline to share with the public.

In our meeting, Thompson stressed the deliberate process was key to the whole thing, and when RANGE asked if she was worried the board would just do whatever they wanted, regardless of her recommendation or her plan, Thompson said she “would be really shocked,” if the board ultimately voted against whatever recommendation she gives in September.

But during the July 25 BOH meeting, Patricia Kienholz, the board member representing Public Health Consumers, said that “personally, I’m ready to go on to step two,” before even having seen Thompson’s recommendation or any of the data and information collected in step one.

“I don’t see what’s wrong with moving into step two,” Kienholz said. “If it’s just to continue the Feasibility Study and identify more concrete things related to cost and community impacts and so on, it seems like that’s what we were trying to do already.”

When asked for more context about her comments, Kienholz told RANGE, “The organization hasn’t developed a stance on this topic yet and the best person to ask about that is Dr. Thompson because she is the lead person at SRHD. [In my opinion] the feasibility study is a way to collect data and consider options. I am certainly interested in public input and invite people to email me at SRHD to consider any relevant information. This is a long process that if and when it’s an agenda item the board will consider fully.”

Other board members expressed that they were no longer sure about the detailed process that had been proposed by Thompson and approved by the board back in April, and would rather simplify it — moving to step two unless there were any clear reasons uncovered in step one that would make privatization inviable.

Board member Dr. Monica Blykowski-May said in the meeting she wasn’t sure she was equipped to use the decision matrix Thompson had proposed as an objective decision-making tool to weigh the recommendation, and instead, unless “huge barriers,” like a “massive community uproar,” were present, they should just move forward.

RANGE interviewed Thompson again on August 2, after the board meeting, and asked if she would still be really shocked if the BOH votes against her upcoming recommendation.

She paused for a full five seconds before answering.

“Yeah. But I also want to put a caveat to that. It is their decision,” she said, “and if they disagree with my recommendation, then it is actually their responsibility to vote the way that they believe is in the best interest of the community.”

In order to ease some of the board members’ concerns with the complexity of her original decision-making matrix, Thompson said she’s been working with the BOH’s policy-making committee to present a second, simpler matrix the board members can use to help them make an objective, data-informed decision on her findings and recommendation in September.

“I’m going to present the findings of the data collection that I’ve been working on since April 25,” Thompson said. “And I’m trusting and believing that the BOH is going to make the best decision in the best interest of the community.”

The fears and the stakes

Not everyone has Thompson’s level of trust in the BOH.

Right after the July meeting, morrow reached out to RANGE to express frustration and even panic that the board’s decision was no longer interested in following the process that had been publicly approved and messaged to vulnerable community members who were participating in step one.

“When I watched the Board of Health meeting in July, my heart sank because I felt like the Board of Health did not understand or was not clearly paying attention to the process that they agreed to,” morrow said. “What the commentary in the July meeting made clear was that a number of folks were so eager to move forward in this conversation that they forgot their responsibility to think about the impact of this conversation.”

morrow said they received several calls from patients referred by SRHD staff who were scared to talk directly about privatization with staff themselves. Two of those calls, from separate patients, confided that they were seriously considering taking their own lives if the division was privatized.

After the first phone call, morrow cried. “I felt a lot of pain and sadness for that person, and I want to make sure that these people are okay,” they said. “The thing that made me the most sad was that I’m worried that visceral fear will be lost in public process.”

“Even asking the question with the best intent has caused people to be very afraid and put their recovery at risk,” morrow told RANGE. “It made me sad and definitely hurt my trust in this Board of Health.”

morrow said the casualness with how the board initiated the study and continued conversations at the July board meeting around whether to speed the process up suggests board members don’t fully appreciate how deeply patients depend on not just the services provided, but the importance of stability, trust and dependable faces and routines in the recovery process. “[It] shows me that they are very far removed from the kind of day-to-day work that so many of us are doing right now, where we are watching people die on the streets of overdose.”

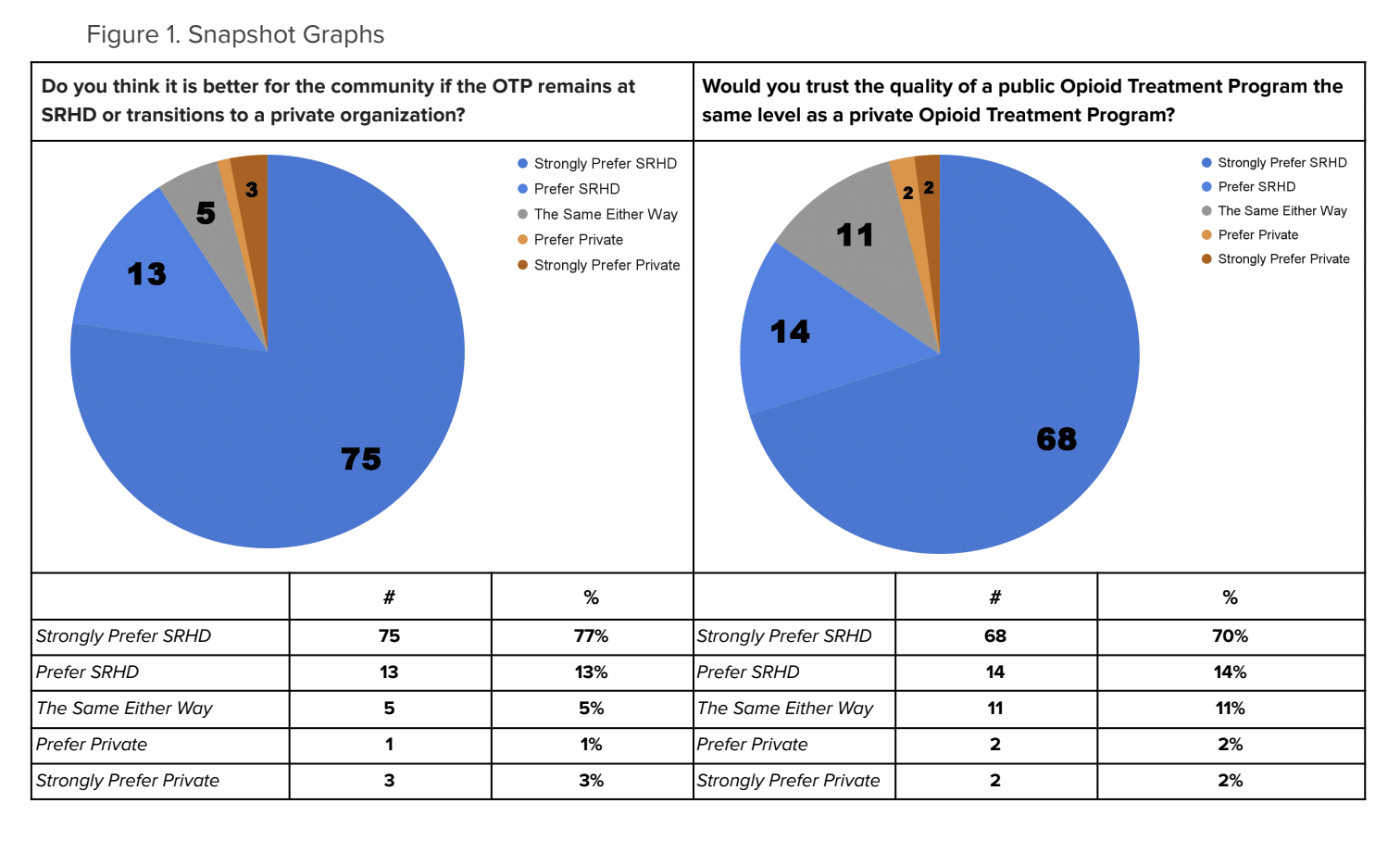

morrow shared the community feedback with RANGE, and the findings were stark: overwhelmingly, participants shared that they wanted the Treatment Services Division to remain public and inside SRHD. 90% of respondents said they believed keeping it public was better for the community, with 74% saying they believe privatization would harm the quality of the care people receive. Less than 5% of those surveyed thought privatization was a better option for the community or would lead to better care.

For the patients, employees and community members morrow surveyed, the stakes of the study were extremely high.

“If the clinic separated, I would have a hard time trusting them and I wouldn’t stick around. Drugs are cheaper than paying out of pocket,” one anonymous response read.

“I’m begging those who are in charge of SRHD to please not let go of such a one-of-a-kind service that is the backbone of thousands of people's recovery. Whatever money would be gained by separation is not worth the loss of life, of hard working moms and dads, that rely on this service to survive,” another wrote. “Please do not trade sober lives for monetary gain. Please!”

In the report summary, morrow wrote, in part: “Out of all 752 comments, there were exactly nine across ALL categories that expressed explicit preference for privatization, which came from five different individuals.”

Of the five people who were in favor of privatization, morrow notes that three identified as having loved ones addicted to opioids, “but none self-identified as users of OTP at SRHD or otherwise.”

A consistent theme across survey responses that morrow observed was that “people do not believe that they will be valued as humans in a private model, that even with best intentions, a [private] provider will be forced to treat clients as a profit model in order to continue to have a paycheck.”

One survey participant described it as feeling like “being sold out to a private option.”

Responses from the survey, and comments shared at the Town Hall RANGE helped organize in July, also highlighted mistrust in the SRHD’s board.

The survey asked participants to identify weaknesses with SRHD’s current Treatment Services Division. 62% of the weaknesses identified were related to “challenges with governance” and “perceived conflicts of interest” from leadership.

Some responses pointed towards past controversies, like the termination of Dr. Bob Lutz, the board’s response to COVID-19, the abrupt termination of a cancer screening program and the statement from Thompson at the Town Hall that she was asked to begin the feasibility study by both the BOH and Misty Challinor, the current director of the Treatment Services Division. (Previously, Thompson had just said she began the process because when she first started at SRHD, she heard a lot of conversations about potential privatization floating around).

One survey response said members of the BOH “let the politics of their political careers guide their decision-making rather than what’s best for the health of the community.” Another said a weakness of SRHD’s treatment services was leadership’s “political disdain for those struggling with [substance use disorder].”

morrow also held two closed feedback sessions with providers who serve Urban Native people or offer Indian Health Services. Recent reporting from InvestigateWest detailed the stark disparities in health outcomes for indigenous Washington residents, which showed that while life expectancy for Washingtonians of all other ethnicities has grown in the last 24 years, life expectancy for indigenous people has decreased by about two years.

The overarching theme from those sessions is that the Native community will not trust decisions made by the BOH until they fill the long-vacant Tribal seat on the board, a controversy RANGE has reported on previously.

“The BOH is not complete without the tribal seat,” one respondent said. “This has always been a gathering place for Natives and we can think about how to be more inclusive of a regional model. This looms in my mind whenever I get invited to do work at SRHD - that the board is not complete.”

Another participant put their position more bluntly: “It will be hard for me to trust any decision this Board of Health makes until the County fills their requirement to fill the Tribal Seat.”

The next steps

While community members have voiced fears that SRHD is on the fast track to privatization, regardless of patient or employee concerns, nothing is a foregone conclusion yet, according to Thompson and Spokane City Council Member Michael Cathcart, who serves on the Board of Health as the representative for the cities and towns that are a part of the SRHD.

Thompson still has to present all of the information and data she’s collected and then give her official recommendation on whether the board should move forward to the next step or not. Then, the board will have to vote on whether or not to approve her recommendation.

Cathcart said that while he views the Treatment Services Division as “a very challenging service,” for SRHD to provide, he takes his responsibility in the process very seriously. Whatever the board decides to do, he said, he would not consider any option that ends treatment services without a quality alternative provider and a transition that doesn’t lose patients in the gap.

“We have to make sure that it's seamless access for those who are existing clients. I think everybody knows how frustrating it is to change providers of anything and have all this paperwork,” he said.

Another especially important issue for Cathcart — given the number of people in the program who also live in poverty — is whether a private provider could give the same level of care at no cost to the patient as SRHD currently does. “Can we make sure that the folks who are essentially fully subsidized or partially subsidized, that they are continuing to get that support?” he said. “Making sure that those folks are getting cared for is truly important.”

“Nobody wants to just suddenly turn people over to an addictive lifestyle,” Cathcart added. If a provider couldn’t continue to provide care to the most vulnerable, like those on subsidized treatment, “that would be a disqualifier.”

He said the big questions he needs answers to are whether the opioid treatment program can be accomplished in a better, more cost-effective way by a private provider.

Cathcart said he’s looking forward to Thompson’s presentation in September and anticipates being able to make a decision on whether the process should move forward after taking in the information.

As for the community mistrust, Cathcart said everyone on the board is “very thoughtful,” and he didn’t think they were “trying to leap ahead.” And, he stressed, “just because we go from step one to step two does not mean that we actually execute.”

Thompson told RANGE that she looks at the fear and mistrust in the process from a behavioral science perspective. “The unknown is always scary. Regardless of who we are as individuals, the unknown is scary,” she said. She also added that should the BOH decide to move forward with privatization, regardless of what her recommendation ultimately is, she will work to ensure there is no gap in care for any clients.

Still, despite these reassurances, morrow is worried the process that was approved months ago and messaged to the public will not be followed and that the BOH will move forward to step two regardless of Thompson’s initial findings and recommendation.

“If what the BOH really wants is to figure out what is best for community, I think the answer is clear. It's pretty loud — it's not [privatization],” morrow said. “If this is a question of, does the BOH want to do programs that aren't foundational core services, then they approved the wrong Feasibility Study.”

Because the decision about whether to continue the Feasibility Study has not been made yet, there are still opportunities for public comment, including a limited amount of testimony slots during the September 26 meeting, which will be held at 1:30 pm in the first floor auditorium at the SRHD Building (1101 West College Avenue). Folks can also email testimony to public_comment@srhd.org before noon on September 25.