When she first conceived, Sara, a young woman living in Spokane, thought she wanted a child with her then-partner. But, she had recently lost her job and health insurance and her partner was living in a different country. They decided together to end the pregnancy and to try again in the future, and Sara used an online service in which a nurse practitioner spoke to her and quickly sent her a prescription of mifepristone and misoprostol — oral medications that can be taken in tandem to end a pregnancy in its first 10 weeks.

“It was almost like taking a vitamin,” she said. “It was completely easy. There was no symptoms at all for me.”

When she took the misoprostol — the second part of the pregnancy-ending regimen — Sara experienced some cramping, but, “it wasn’t anything I couldn’t handle with Motrin, a heating pad and a warm shower.

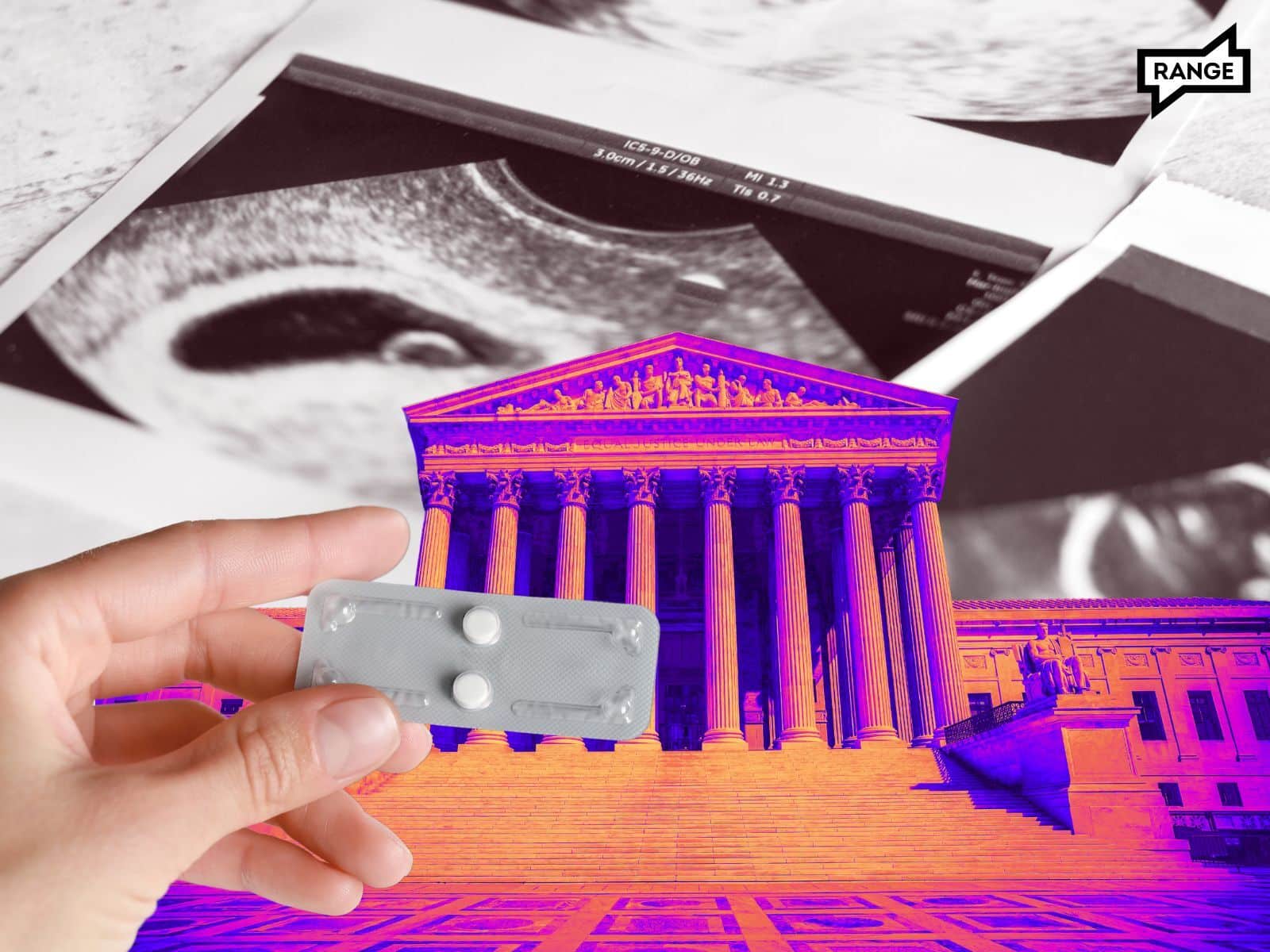

The use of mifepristone, one of the drugs that allowed Sara to get a quick, easy and safe abortion, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000. But a recent case in the Supreme Court — FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine — could roll back critical access to the drug, even in blue states like Washington that are seen as reproductive health care safe havens.

Since it was first approved, the use of the drug has grown rapidly. The FDA estimates that from the time of its approval to the end of 2022, about 5.9 million people in the U.S. have used the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol to end pregnancies. Mifepristone is also prescribed to minimize risks that commonly follow miscarriages and is shown to cause fewer fatalities than both Viagra and Tylenol. It now accounts for nearly 60% of the abortions performed in Washington.

In 2016, the FDA found it was safe for it to be prescribed up until the 10 week mark of the gestational period, expanding access from the previous prescription period of seven weeks. In late 2021, the FDA again expanded access to the drug by allowing certified pharmacies and clinicians to distribute the medication via telehealth appointments. Then, in January 2023, the agency approved a protocol for pharmacies to dispense mifepristone directly to patients.

The Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine sued first to argue that the FDA never should have approved mifepristone in the first place. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the first challenge to the drug, but in favor of The Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine’s subsequent pushes for a rollback of the more recent decisions by the FDA that increased access by allowing mifepristone to be prescribed via telehealth and up to the 10-week mark of gestation.

The FDA and mifepristone manufacturer Danco asked the Supreme Court to review the lower court’s ruling, stating that the FDA had followed correct scientific procedure in its approvals of the drug. They also argued the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine faced no harm from expanded access to mifepristone, and therefore lacked standing to bring a case against them.

The Supreme Court heard arguments from both sides in late March, and will likely decide by the summer whether to uphold the decision made by the conservative Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals last August.

If they side with the lower court, patients would no longer be able to access the medication via telemedicine, pharmacies would likely no longer be able to dispense it and it would only be available for the first seven weeks of pregnancy, instead of the first 10 weeks. While that three week difference may sound insignificant, statistics from the CDC show that almost half of all medication abortions happen after seven weeks of pregnancy; because gestational weeks are counted from the last day of a person’s period, many people don’t notice a missed period until they’re four or five weeks pregnant.

The ability to access the drug via telemedicine has been both an easier option for patients to access care, and a critical way of minimizing the burden of prescribing abortifacients on doctors in blue states who have found their offices flooded with people seeking care from states with restrictive abortion rules.

For Sara, the ability to seek telehealth was crucial. She used mifepristone a second time in November 2022, after the Supreme Court allowed states to ban abortion. Her now ex-husband had just moved to the states on a marriage visa to be with her, and though Sara was on a new birth control, it didn’t work, or hadn’t kicked in yet — she got pregnant again.

At the same time, she was facing escalating physical and emotional abuse from her then-husband. “I grew up with lots of abuse and I did not want to bring a baby into the same life,” Sara said. She went through the same online service and received another prescription for mifepristone.

“I really regret getting pregnant the second time. I felt a lot of shame that it happened again,” Sara said. “I felt very alone, like I couldn’t talk to anyone.” But, the nurse practitioners talked to her virtually every day about any side effects or fears she had, and even helped prescribe her a birth control that works well for her.

Sara has since left her abusive partner and one day, after she finishes nursing school and if she meets the right partner, Sara said she still hopes to have a child of her own.

Washington impacts

Though its legislators describe Washington as an abortion sanctuary state, all of these restrictions that impact access to mifepristone would also apply in Washington.

Still, Washington officials have already begun planning to protect the state’s patients, which include people traveling from neighboring states with stricter abortion laws to receive care. The Department of Corrections, which has a pharmacy license, maintains a stockpile of 40,000 doses of mifepristone. Gubernatorial candidate and current Attorney General Bob Ferguson announced it would be possible to continue dispensing the state’s stock of medication up until the 10-week mark. What that rollout would look like and how those 40,000 pills would be distributed and dispersed through the state is unclear, and will likely remain so unless the Supreme Court ruling this summer forces the AG’s hand.

When Sara learned about the mifepristone case before the Supreme Court, she was shocked and started following the debate around it.

Sara said that being so close to Idaho has been a wake up call for her, as she thinks about her own access to care. During her second medication abortion, she experienced a lot of bleeding after taking her dose of the misoprostol. She just wanted to run to her mother for comfort — but Sara’s mom lived in Post Falls, just across the border.

“I just felt like, ‘Oh God, if I have complications or anything, I could get arrested in Idaho,’” Sara said. “So it's very eye-opening. I feel really awful for women and places that don't have access.”

RANGE also spoke with Molly, a woman who moved to Spokane from Idaho in 2019 seeking an environment with less reproductive care restrictions for both her and her teen daughter.

Despite consistently using birth control, Molly is no stranger to unplanned pregnancies. The 40-something Spokane resident — who asked to use her first name only to protect her privacy — chuckled a little as she described what she called her strong “fertility gene.”

“My family is ridiculously fertile, so I’ve had a few run-ins over the years,” she said. “My body just hates birth control, and so I have yet to find one that has worked for me anything close to long-term.”

Molly had her first unplanned pregnancy when she was in college. Mifepristone had just been approved by the FDA for ending pregnancies, and was not yet commonly prescribed, so Molly felt her only option was to have a surgical abortion, or a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure.

About 20 years later — and now a mother to a teenage daughter — Molly changed jobs in 2021. With that came an insurance change and, suddenly, she was unable to continue receiving a delivery of a three months’ supply of her birth control at once. The inconvenience caused her to reevaluate whether she even needed it at that point.

She thought, “Well, I’m 40, about to be 41. Is it really a major concern for me these days? Maybe not.” But her “fertility genes” were too strong, and she had an unplanned pregnancy in the spring of 2021.

Molly wasn’t looking to have another child. She already had one daughter, and, “Parenting when you’re 25 versus parenting when you’re 40 is a different beast,” she said.

So she went to Planned Parenthood, and received a prescription for mifepristone and misoprostol — oral medications that can be taken in tandem to end a pregnancy in its first 10 weeks. The staff was supportive and kind, she said, and at the end of her appointment, she left with what she’d come for.

“You come in, you talk to someone, you get given the pills, you get to go home, change into your comfortable clothes, sit and watch TV and not have to be out and about, be in a hospital setting or anything like that,” Molly said. “It's just kind of on your own terms. The entire experience was miles easier than the surgical abortion that I had. … When you compare it to the medication abortion, it's night and day.”

While Molly, who has actually had a couple of medical abortions since her first in 2021, is less concerned about her own access to care now — her long-term partner is about to get a vasectomy — she is worried about what kind of access to care her teenage daughter will receive, especially if she chooses to go out of state for her college education.

“I moved from Idaho because I did not want to parent a teenage girl in Idaho,” she said. “I feel like a reproductive rights refugee.”