Two proposed policies — one of which copies Trump, Texas & Georgia — seem designed to challenge Washington laws and education policy

The Mead School District Board will have its first reading of two separate policy proposals aimed at censorship on Monday night. One is designed to prohibit any literature or materials referencing “gender identity, gender fluidity … or gender-neutral ideology in any form in Elementary libraries.” The other would prohibit, among other things, the compulsory teaching of “‘Critical Race Theory’ curricula or ideology” in civics education. (While CRT in schools is a huge topic on the right, most public school officials and teachers — including at Mead — deny this graduate-level academic concept is being taught at all.)

The policy concerning critical race theory (CRT) is a newly proposed policy concerning “Civics Education.” The LGBTQ+ prohibitions would be added to the District’s existing Library Media Center policy.

The CRT policy tries to do a lot of things in two and a half pages, including requiring teaching “diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to any one perspective,” prohibiting grades, course credit or extra credit for political activism and lobbying, and prohibiting the punishment of students for voicing unpopular opinions.

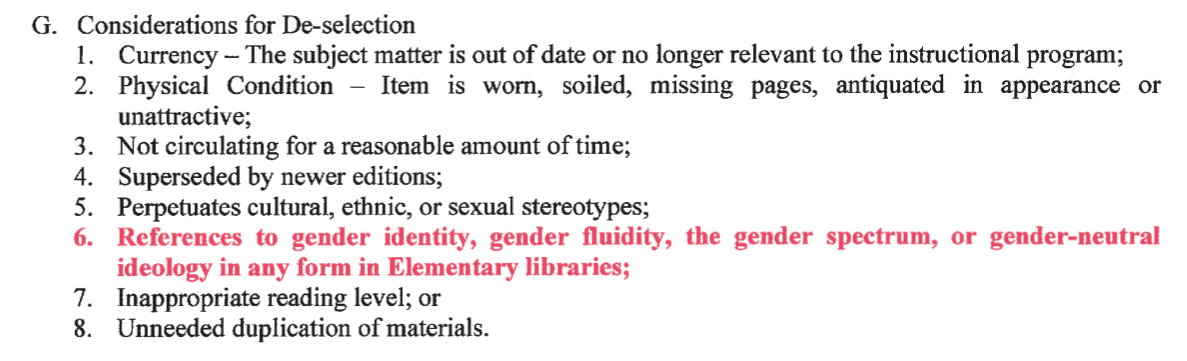

The library policy revision is remarkably straightforward: If a book or piece of media has anything that paints outside of a strict gender binary “in any form,” it cannot be kept in Mead elementary collections. If such books are already in those collections, they must be removed. The policy revision does not specify changes for middle and high school collections.

Both the new Civics Education policy and the revision to the library policy were written by Board Director Michael Cannon and will be presented by him at the meeting tonight. The civics policy specifically has deep roots in the national anti-CRT movement and draws heavily — sometimes verbatim — from an executive order signed by Trump in late 2020 and a state law passed in Texas last year.

It’s not clear yet how the other four members of the board feel about these policy revisions, though four of the five currently sitting members were on the board in 2020 when they unanimously sent a letter to Governor Jay Inslee asking him to not to sign the 2020 sex education bill. That bill mandated comprehensive sex education in Washington schools and forbids abstinence-only curricula. Opponents of the bill challenged it with a 2020 referendum that was defeated by more than 15% points statewide.

The only current member who wasn’t on the board back then, BrieAnne Gray, ran to the right of her opponent, opposing not just comprehensive sex ed, but also COVID mask mandates, and the teaching of critical race theory.

Given that board composition, these policies may be likely to pass. What’s less clear, though, is whether they can withstand Washington State’s anti-discrimination laws and a specific recent focus on creating gender-inclusive schools. It almost seems as though Cannon’s policies were written to force a confrontation with the state.

Writing Gender Out of Library Policy

Mead’s current Library Media Center policy is a brief, three-page document that sets general guidelines for developing a collection that meets “the unique needs of each school,” including media selection criteria, a gift/donation policy, and guidelines for “de-selection” — the routine process of culling outdated, damaged or duplicate materials.

Over one quarter of the policy deals with resolving complaints from community members, and begins by telling library staff to “consider both the citizen’s right to express an opinion and the principles of intellectual freedom.”

Wide latitude is given to library staff to make choices that are appropriate for their specific school. No categories or topics are specifically prohibited, though staff are asked to consider de-selection of materials that “perpetuate cultural, ethnic or sexual stereotypes.”

Cannon’s draft keeps much of that latitude, with one big exception: the new policy explicitly prohibits any expressions of gender fluidity “in any form” in elementary libraries.

For books already in elementary collections, Cannon’s policy revisions mandate their removal.

We haven’t yet seen any legal guidance on whether this policy would violate Washington State’s anti-discrimination laws, but gender expression and gender identity are protected classes in Washington. It’s also worth noting that the language of this proposal appears to ban references to gender identity in general, which could mean any book with people defined by gender would be subject to removal: Goodbye Hardy Boys, so-long Little Women.

The state law that prohibits discrimination in schools, 28A.642, specifically directs schools to adopt “at a minimum, all the elements of the model transgender student policy and procedure.” The law states definitively that the model policy is intended “to eliminate discrimination in Washington public schools on the basis of gender identity and expression; address the unique challenges and needs faced by transgender students in public schools; and describe the application of the model policy and procedure prohibiting harassment, intimidation, and bullying, required under RCW 28A.600.477, to transgender students.”

The law explicitly gives enforcement authority to the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), and OSPI, for its part, makes no distinction between kindergarten-aged kids and high schoolers when it comes to gender-inclusive education: “Civil rights laws prohibit discrimination and discriminatory harassment on the basis of gender expression and gender identity in Washington public schools. All [emphasis theirs] students have the right to be treated consistent with their gender identity at school.”

That doesn’t mean that every grade in Washington public schools will be taught about sexual activity — as fearmongers have claimed. For grades K-3, Washington’s sexual education curricula is focused on social-emotional learning, which “provides skills to do things like cope with feelings, set goals, and get along with others.”

The OSPI guidance on gender-inclusive schools does not explicitly discuss libraries or book prohibitions, but their language and guidance for things like using preferred names, pronouns, restrooms and locker rooms is unequivocal.

Given all that, it’s hard to see how a blanket prohibition on books with any treatment of gender fluidity wouldn’t be considered discriminatory.

The enforcement authority given to OSPI allows for significant penalties, including termination of the offending programs, “termination of all or part of state apportionment or categorical moneys to the offending school district … and the placement of the offending school district on probation with appropriate sanctions until compliance is achieved.”