Editor’s note: This article describes self harm.

A man was in such mental distress that he bit off two of his fingers and severed one of his testicles. Guards withheld toilet paper from women who rejected sexual advances. Another man became so lonely that he took to dialing random phone numbers, hoping a Samaritan would listen to his stories on a collect call.

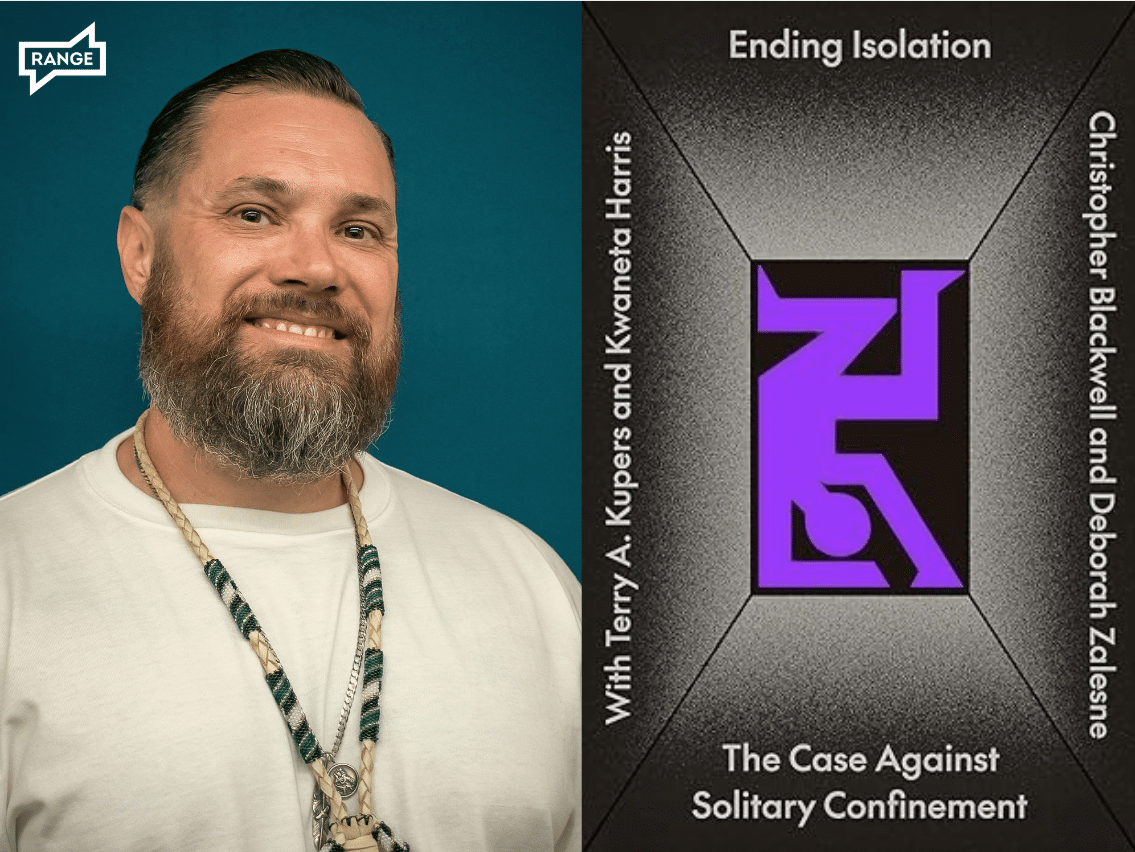

These are a few of dozens of stories from American prisons told in a new book co-written by Christopher Blackwell, a journalist incarcerated at the Washington Corrections Center (WCC).

Ending Isolation: The Case Against Solitary Confinement, published by Pluto Press, is being promoted prior to its September 20 release on the nationwide Journey to Justice bus tour. The tour, co-organized by Blackwell’s nonprofit Look 2 Justice and the advocacy organization Unlock the Box, will stop in Tacoma on September 12 and in Seattle on September 13 and 14. The events are free to attend, and you can RSVP here.

These stories describe solitary confinement, also known as “the hole,” a practice American prisons have used for decades to manage incarcerated people. Prisoners are shut inI a concrete box, sometimes the size of a walk-in closet, for 22 to 24 hours every day. Most of their possessions are taken from them. Some spend decades in isolation, often suffering abuses free people never have to think about.

Prisons in the US and other Western countries say they need the practice to provide health and safety to the world’s largest prison population.

But prison reform advocates say solitary confinement — which has a technical definition but is used to describe a wide variety of practices prisons use to separate incarcerated people — is expensive, counterproductive and amounts to torture. Samuel Fuller wrote in the Chicago Journal of International Law that countries that use solitary confinement to manage their populations are violating the U.N. Convention against Torture.

Blackwell is an incarcerated journalist and activist working from a small desk with a smart tablet and calendars covered in sticky notes in his cell at the WCC in Shelton. He spent the last several years putting together the book, which weaves the legal and medical aspects of solitary confinement with the human stories of people who suffer it, including Blackwell. He wrote with Kwaneta Harris, another journalist incarcerated at a women’s prison in Texas; Deborah Zalesne, a law professor at the City University of New York; and Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist based in Berkeley, California.

RANGE spoke with Blackwell — who has spent time in solitary confinement — this week to ask him about the project and his goal of ending the practice entirely. Here’s that conversation, which we’ve edited for clarity and length:

RANGE: You work from prison and face barriers that other writers don’t. How did this book come together?

Blackwell: About two years ago I was talking with professor Zalesne and said, “We should really partner on a book — you could talk about the legal angles of it, the cruel and unusual punishment of solitary confinement. I could talk about the real life experiences and the harms and the traumas that it's put on my life.” And [Zalesne] was super into it.

I wanted to make sure that we're including voices of people from all different communities. People from the women's prison, people from the LGBT community and stuff like that because there's so many aspects that change and weave in a different way. I didn't want to do that thing where you just kind of blanket speak for something even though I experienced my first time in solitary at 12 years old. I'm an expert for youth male experiences, not females’ or other’s experiences. So we put out a pretty wide net and then narrowed it down to the people we thought would be really good fits and cover all the demographics. [Harris] is incarcerated in Texas, and she's a brilliant writer, but she started telling me and [Zalesne] all this crazy stuff that women go through. I shouldn't be speaking for women.

Then we started weaving in stuff from reports from Dr. Kupers and Dr. Craig Haney, because they're some of the leading experts in the country — in the world — on solitary confinement. I was like, ‘I'm just gonna call Dr. Kupers. He has decades of experience. He's interviewed hundreds of people in solitary confinement and written so much about it. He's a close friend. I reached out and said, ‘Hey, how do you feel about coming on this project?’

There are two kinds of solitary books out there: the anthology of sad stories, the sad puppy in the window, right? And then there's the academic one that's really difficult to read and a lot of data, material and numbers.

I wanted to merge those.

RANGE: Solitary confinement was initially brought to the United States by the Quakers who felt solitude would help people move on from criminal behavior and tendencies, but as the book outlines, that experiment was a failure and solitary was abandoned for decades. Can you talk about the reasons why the practice has resurfaced in American prisons as the prison population ballooned?

Blackwell: We deal with this a lot when we think about a prison system that was expanding so rapidly. It seemed unmanageable probably to prison staff to not have a tool like this at their disposal. How do you manage such a large portion of a population?

This opened up a tool as we expanded into mass incarceration for guards and prison administrators to manage prison populations at such a high rate. You can see mass incarceration balloon, especially in the 1980s, to an unsustainable point. And I think that's when these tools started to resurface. The Quakers quickly realized that it wasn't working and retracted wanting to use that or promote that in any way and made it very clear that it was a failed experiment.

RANGE: The book talks about additional punishments — such as beatings, physical restraints and lost meals — that are over and above the actual isolation that you experience in solitary. These seem more punitive than rehabilitative. Why do you think they do that?

Blackwell: It's like strip searches inside prisons, right? These things derive from times of slavery. They're meant to abuse and oppress. That's all. They're exactly what they sound like. They could be painted as if they’re for the safety and security of prisoners inside.

Bullshit.

Most people in prison have had severe lack of education, have been physically, mentally and sexually abused in some way, have lived in survival mode their entire lives. And then you put them in a box to process all that trauma without any support or training. People on the outside world go to psychologists with far less trauma than most people inside have to deal with. And they expect us to figure that out on our own?

They have a guard — a lot of these guys couldn’t even pass a test to be a police officer because they weren't deemed fit to do that. [Editor’s note: the Washington Department of Corrections requires guards to pass a school called the Correctional Worker Core Academy.] But they're fit to take care and manage people that are far more damaged. I've seen people suffering from extreme mental health problems and because [the prisons] have nowhere to put them and they don't know how to deal with them, guards and administrators shove them in solitary.

[In solitary,] even the most capable human beings completely break down and deteriorate. It's hard to watch. It's hard to listen to. You have guys that break down so bad, they start playing with their own feces, rubbing it on the walls, on themselves.

There's just no reason that we would put people in these situations and expect that this is gonna do anything beneficial. The only benefit is that guards will have a way to hang something over your head and do the ultimate to you.

RANGE: You and others say that, once you're out, you tend to have very hazy, blurry memories of being in solitary. Can you talk about why it's so hard to remember time in solitary?

Blackwell: I grew up in a really abusive childhood, through my father. For me, there's a few moments that I remember, but a lot of it is extremely hazy and I just can't remember what happened, because it's such a traumatic moment that, in that survival instinct of the human body, you push it and box it and isolate it somewhere.

I think that that's one of the things that solitary creates, one of the things that we don't even realize that it's creating. It’s part of your soul, man. It really takes you to a different place.

People have distractions to keep going through the world and not having to process every bad thing or every little traumatic thing in our life. If [you’ve been isolated] for weeks, for months, years, decades, and having to really relive the things that can come up out of your mind, it's really crazy, the things that start to surface. Without the proper support of processing those things, it can be really traumatizing.

People completely shut down. That's why it becomes hazy.

What I would always have to do is like, right when I get to solitary, I set up a pattern and a schedule. I'm gonna work out there this time. I'm gonna wake up, I'm gonna comb my hair, I'm gonna make my bed, I'm gonna leave for an hour. I'll have my yard time, and I'll go call my family, and then I'll come back and write letters for an hour. If you don't do that, you can't make it through and it gets hazy.

RANGE: You characterize as solitary as torture and assert that solitary is unconstitutional because it's cruel and unusual. Can you talk about why American society has not moved toward abolishing it?

Blackwell: We haven't moved towards abolishing it because the courts have used the terms “safety” and “security” so loosely, and the courts refuse to define that for prisons by saying they're not the experts, so let the experts handle that. The “experts” are prison administrators and prison guards and their unions. It is continuously stated that prisons would devolve into utter chaos and disarray if we got away from solitary confinement, that they have to have that tool. As a society we have allowed it to continue because we're just not educated enough on it.

You could probably go ask 10 people — random people in the streets — and I'd be shocked if you found one that could actually break it down to you. People don't know. That's why it happens in the shadows, and a lot of the time people don't care because people will be like, “Well, you're in prison. You deserve whatever you get.”

That kind of thinking is exactly why we still deal with recidivism and crime rates at the level that we do, because we're not thinking with the brain of let's fix the people causing harm. Let's work with them. Let's see why that's happening. Let's pull people out of what I continue to call survival mode and get people into a space where they feel like they belong. Because when you belong to a community, you wouldn't harm that community.

RANGE: Your book is on tour, doing events around the country. What do you hope people do after they read the book or attend one of these events?

Blackwell: I just want people to leave with a better understanding. It's hard to change something when it's really not in people's face. And this is what's been done with prison systems over the decades: they've moved to be more isolated and contained and operate in the shadows, which means society doesn't know what's going on. The goal is that people attend these events and they learn what is exactly happening inside prisons, especially in solitary confinement units. What are their tax dollars going for? Is that something they actually want? Do they want to be spending hundreds of millions of dollars keeping people in solitary confinement only to have them released worse off? No. Who wants to pay for that?

This is something we can defund. We can get rid of it. It's better for everybody. It's better for humanity.