Sierra Alexander should have been celebrating. She had just earned a Master’s of Fine Arts in creative writing from Eastern Washington University. She was looking forward to the next chapter of her life: following her passion for diversity and inclusion in higher education.

But instead of a happy ending to her time at Eastern, which included dancing for Eastern’s first majorette team, working as a graduate assistant in the Multicultural Center and serving as the president of the Black Student Union (BSU), Alexander was confronting what felt like a betrayal from the university she’d just left.

Former colleagues in the office of Student Affairs had just given her gut wrenching news: her former boss and mentor, Vanessa Delgado, had been fired.

Delgado was the director of Student Equity and Inclusion Services, as well as the inaugural director of the Multicultural Center and the director of the Pride Center at Eastern. In her five years at the university, students and coworkers described Delgado as an outspoken advocate for queer students and students of color. In the wake of Delgado’s termination, a community that was already skeptical of Eastern’s leadership is raising new questions about the university’s commitment to LGBTQIA+ students and students of color, starting with the nature of Delgado’s departure.

Student Affairs employees confirmed that on June 28, following a meeting with former Vice President of Student Affairs Rob Sauders, a sobbing Delgado was accompanied back to her offices by an HR representative, who supervised her as she packed up her things and then escorted her out of the Pence Student Union Building.

Employees confirmed that Delgado had gone into that meeting with fears of being fired, and as she left it, word quickly circulated among Student Affairs staff that those fears had been confirmed.

Delgado herself declined to comment. Her former coworkers declined to comment, potentially due to a university policy that dictates employee communications to media should be approved by Dave Meany, the director of communications and media relations.

Meany said the university does not comment on personnel issues, but it appears the decision was made quickly, and with at least one key person not in the room.

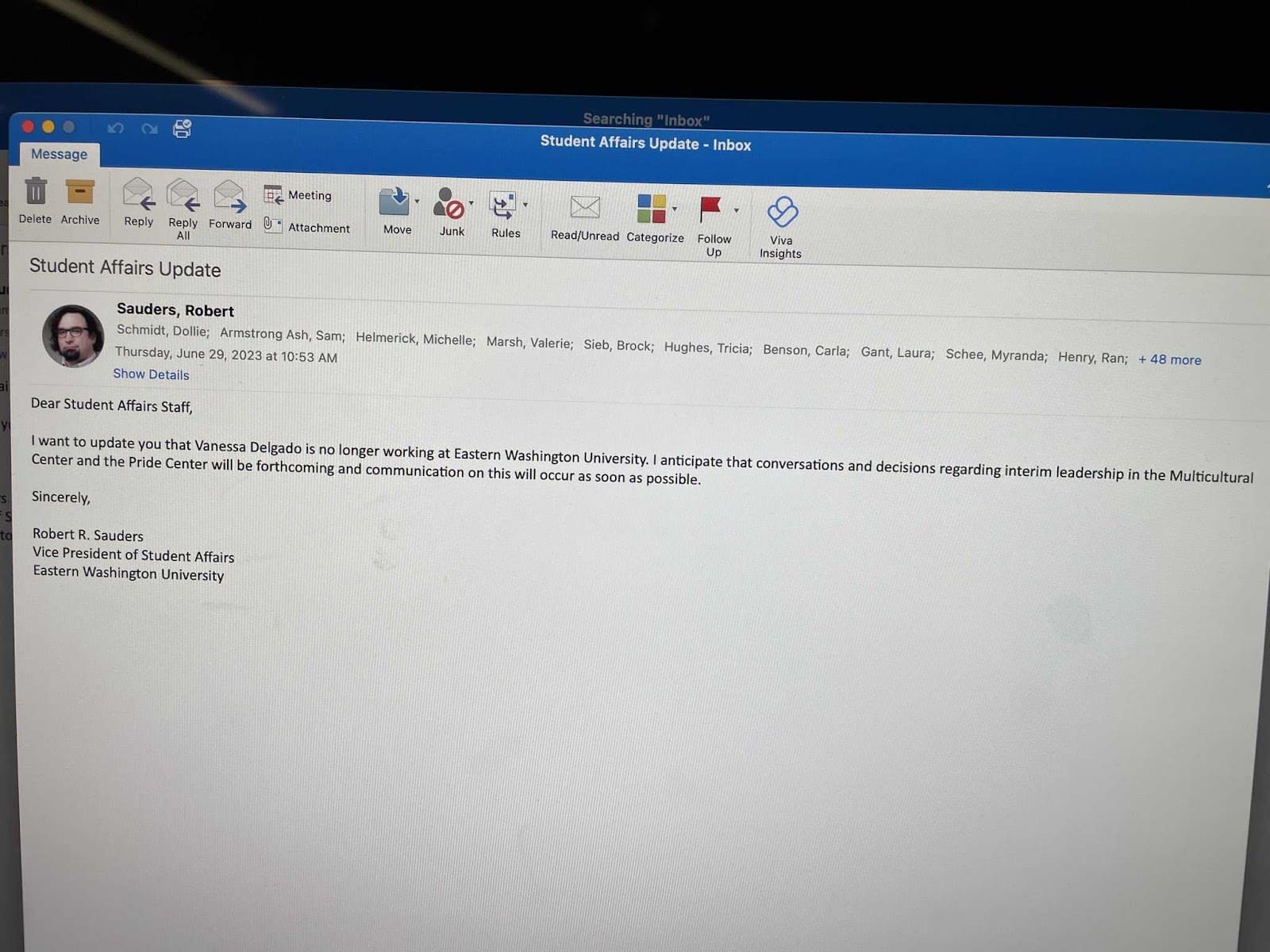

Delgado’s former supervisor, Dr. Nick Franco, was out of the office the day she was fired, and was given no prior notice that their direct report would be terminated. A late June email sent to Student Affairs staff by Sauders show that basic decisions about Delgado’s replacement, even in an interim capacity, had not been made at the time of her separation from the university.

For Zoe Swenson, a student employee in the Pride Center, the abruptness and lack of a succession plan left her scrambling. When Swenson got a text over the summer about Delgado being fired, her mind instantly jumped to the practicalities: Without Delgado, how would key programs for incoming marginalized students function?

“I directly reported to Vanessa,” Swenson said. “I was told by one of my coworkers that she was fired and that sent me for like a whole loop because we have these programming activities that happen before the school year starts that Vanessa was heavily involved in.”

Alexander was on vacation, and even though she’d graduated, she still kept in close touch with her former coworkers, so she wasn’t surprised to get a phone call from someone who still worked in the Multicultural Center. She was, however, shocked by the news.

“It was sudden,” Alexander said. “It definitely was strategic because it happened when there were no students there in the summer, very quiet.”

RANGE interviewed a combination of students, staff members and Eastern community members on background, and the feeling was palpable among these sources that administration and leadership fostered a culture that prioritized preserving university image and punished those who spoke out too loudly against injustice.

A Student Affairs staff member, who asked to remain unnamed due to concerns of retaliation, said: “It seems that the staff in the centers were seen as ‘causing the problem’ when in reality, homophobia, transphobia, racism and sexism exist everywhere, and higher education is not a system immune to them. Instead of taking the time to listen and understand what our marginalized students experience daily, the predominantly white, cisgendered leadership opted to be defensive and blame the very people employed to help those students navigate college and try to keep them enrolled so that they can graduate.”

A trusted community leader

Student leaders interviewed by RANGE said they looked up to Delgado. They relied on her. They trusted her to advocate for them to the administration. And now, they fear she was fired for it.

Alexander had worked closely with Delgado in her capacity as a graduate assistant, including on programs like Eagle Familiarize, Affirm and Matter (affectionately known as Eagle FAM), a program Delgado administered to help ease first-generation students into the campus climate and connect them with peers, mentors and resources. Alexander described Delgado as a trustworthy person who would consistently show up for marginalized students.

Madelyn Roy, who is the Student Equity & Belonging Coordinator in the Multicultural Center but was not representing the university in their personal comments they made to RANGE, said Delgado was a key factor in the success of the Multicultural Center. “Vanessa was able to help students with marginalized identities — especially those who were first generation and new to higher ed — connect to resources, network and find those important campus relationships, and gave them the space to really be themselves at a predominantly white university in a predominantly white place,” Roy said.

At Eastern, 39% of the student body, but only 18% of the staff and faculty, identify with racial identities other than white. Delgado and the centers she led were tasked with building safe community spaces and support networks for students outside the majority. (Eastern does not collect student data on sexual orientation or gender identity.)

Roy would not comment on Delgado’s firing due to university policy, but was willing to talk about her impact and the legacy she left

“I know a lot of our students identify that the centers and Vanessa are very large reasons, if not the primary reason, that they are still at EWU,” Roy said, “and I just hope we can continue to honor what was built here to continue that goal.”

“[Delgado] was always able to help students identify little silver linings or little strengths or moments to celebrate,” Roy said. “Even when they felt really frustrated and overwhelmed by being at an institution that maybe doesn't look like home or feels a little uncomfortable, or where they didn't have a lot of people they related to.”

“I think students and staff alike are going to feel the absence of that kind of support and trust, and I think the reality is simply that the centers are going to be and feel different this year,” Roy said.

#wehaveworktodo

In the six months before Delgado’s termination, Eastern’s campus had been the subject of two student social media campaigns calling attention to the lack of administrative support for students of color and queer students. The campaigns originated on Instagram, from accounts run by student clubs.

Alexander, in her capacity as the president of BSU, spearheaded the first social media campaign in response to targeted racist language found on campus.

On April 11, 2023, Alexander found a racist message written on the mirror of the dance studio that the BSU had been using for five months. In a post that has since garnered over 1,000 likes, Alexander wrote, in part, “It is our right as human beings just like everyone else to feel safe in a learning environment and supported by our university’s executive leadership team, President Dr. Shari McMahan, and the campus community when issues like this occur. We are asking President McMahan and the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion to make a statement condemning racism and anti-blackness. We will accept nothing less than safety, support and respect.”

Two days later, McMahan responded with a statement broadly condemning discriminatory behavior.

Alexander and Spokane’s NAACP president Kurtis Robinson both questioned the strength of the response: “By not naming for the racism it is, by not naming it for the white supremacy culture dynamics that it is, by not naming it, the organizational and personal responsibility to get in front of this and stay in front of this, you’re giving it a hall pass to continue,” Robinson said.

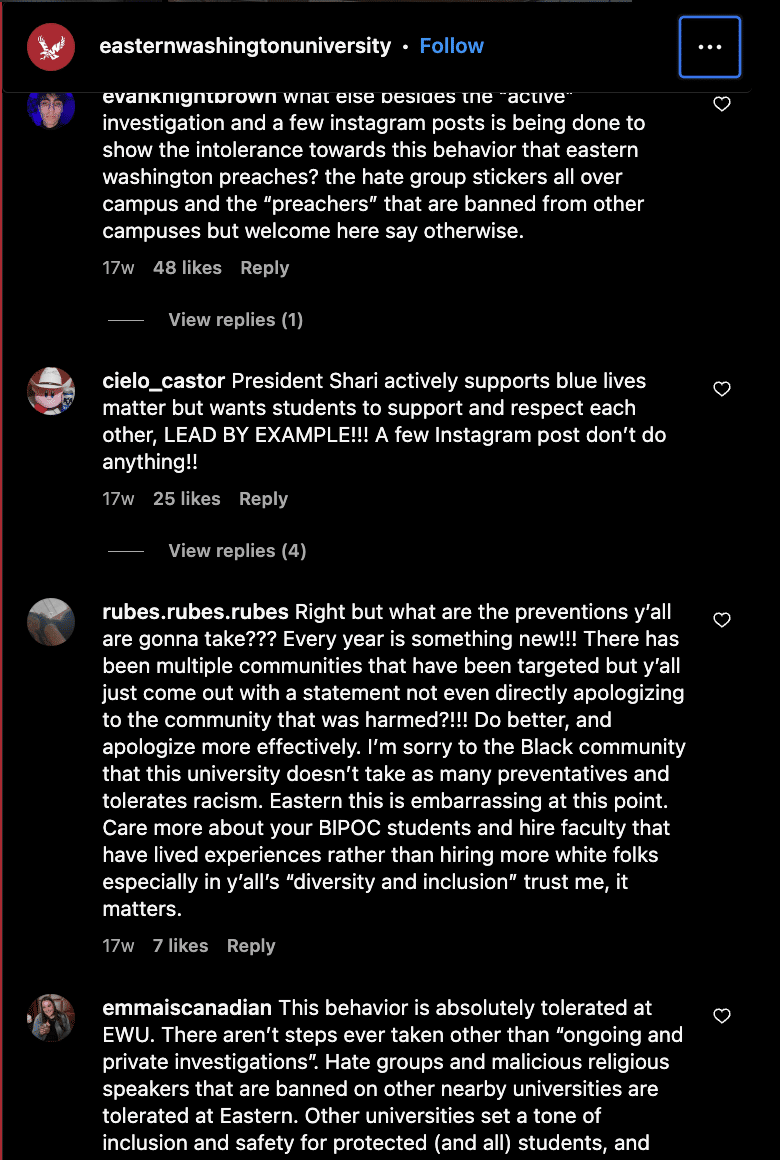

Comments from students on the Instagram post echoed Alexander and Robinson’s frustrations.

On April 21, after eight days and a barrage of local media coverage, McMahan made another statement committing to build a new strategic plan that prioritizes diversity and acknowledging the incident as anti-Blackness.

“When BSU decided to post our experiences on social media and that gained traction, it felt like then they started taking it seriously,” Alexander said. “Some of the initiatives to combat the anti-Blackness that was on campus, they did take really good steps towards.”

Now, though, the termination of Delgado is making Alexander question whether Eastern leadership was really ready to listen and support diverse communities on campus. “In the end, it just didn't seem genuine,” Alexander said. “And it isn't genuine because, to my knowledge, the director of the Multicultural Center was let go.”

Less than two months after the racism directed at BSU made the news, Eastern was again rocked by a hate incident, and the administration again found itself facing criticism over what students characterized as delayed reaction and performative allyship, though this time the hate was directed against queer students.

Here we go again

Swenson, a sophomore at Eastern, speaks with a soft voice, and seemed shaken when she described the events of the spring quarter that kicked off the second social media campaign. For most of her first two years on campus, she existed in a bubble. As a student employee in the Pride Center, she was surrounded by her queer community and constantly engaged with queer students, employees and events. But in June, that comfortable bubble popped.

Swenson, in her capacity as vice president of the Eagle Pride club, had been fundraising across from homophobic preachers speaking outside the Pence Union Building — which houses the Pride and Multicultural Centers — when a student came up to the table to tell club officers that a slur had been written on the door of their dorm room. The preachers were a nuisance, Swenson said, but the university had already told them they couldn’t do anything as long as they remained on public property. The slur on the door felt like a deeper violation, as the student lived on the gender inclusive floor of Pearce Hall, a housing option queer students had fought to have access to in 2018.

Swenson said she and the club encouraged the student to go through all the official channels, helping them report the homophobic incident to employees at the Pride Center and then to Delgado, who helped them file an official university bias report around the first week of June.

Then, crickets.

“It was an awful feeling for me, personally, to be protesting, speaking up, and trying to make a difference while our university stayed quiet during the uprise of homophobia in June,” said Max, a queer student at Eastern who has asked to be referred to by first name only. “Hopefully the university can listen more to students, especially since this school is our home. We deserve to feel safe.”

While Swenson was told that Housing and Residence Life officials “handled it,” and RANGE has confirmed that a housing notification went out to students in Pearce Hall, there was no unified official response or acknowledgement of the harassment queer students were facing on campus.

About a week after Eagle Pride members reported the uptick of homophobic incidents on campus, Swenson said Dean of Students Samantha Armstrong Ash reached out and came to visit the Pride Center. What followed was a conversation Eagle Pride members described as dismissive and questioning of their lived experiences. As they opened up about the kind of support they needed, they said, Armstrong Ash questioned them, saying things like: “Wow, are you sure about that?”

For Swenson and other leadership in Eagle Pride, Armstrong Ash’s response was the last straw.

“When we reached out, we got a very demeaning response of ‘Are you sure that’s how you would like to be supported … blah, blah, blah,’” Swenson said. “Responses like this by Sam Armstrong, and then non-responses — nothing from our president — is not making us feel supported, and we were straight up like: ‘Do you think that our university president is homophobic?’ Because she is not doing anything to support us and take a stance on these homophobic incidents.”

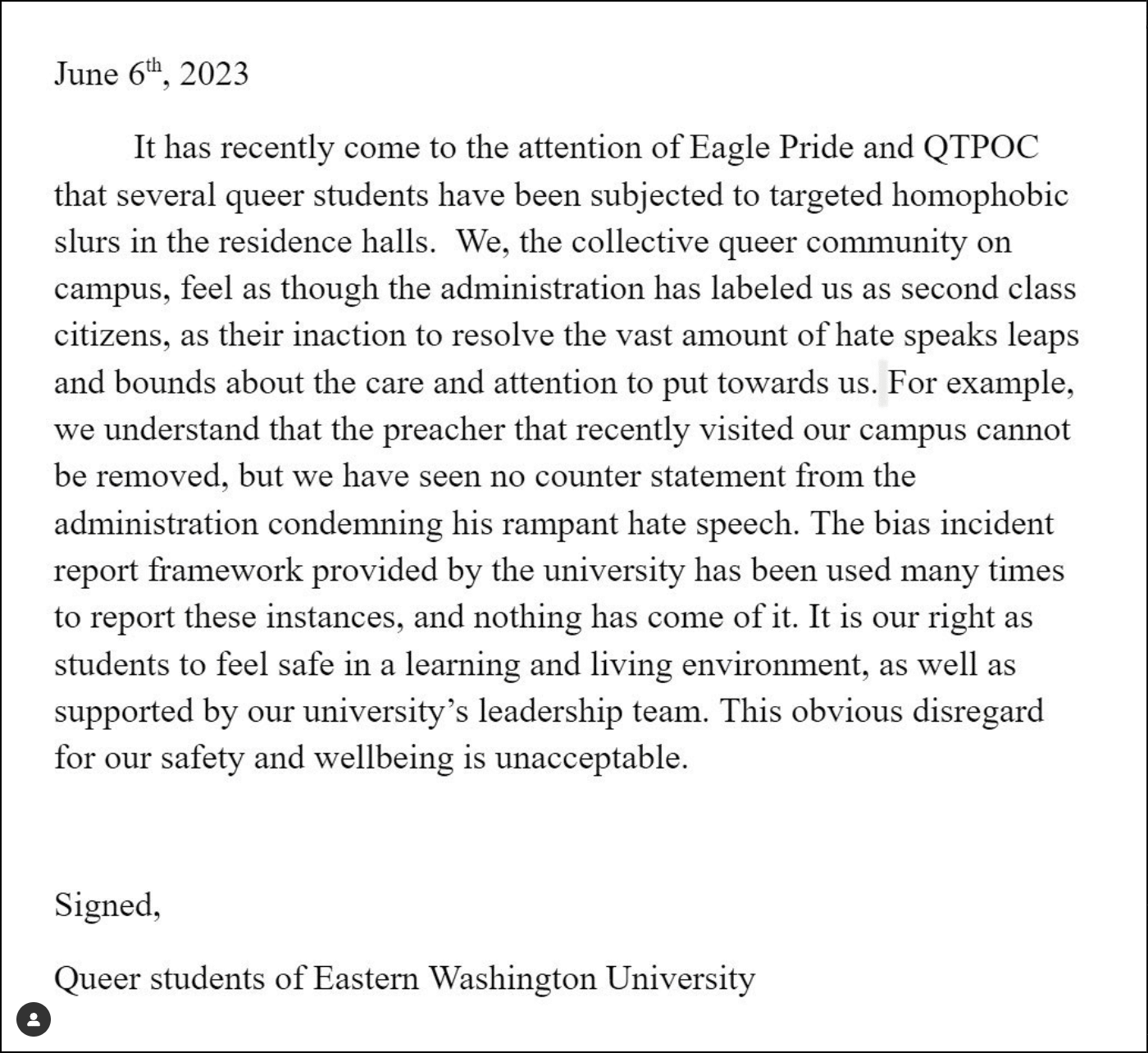

Feeling a lack of response and engagement after the pastor's homophobic rhetoric and the slurs on dorm room walls, the Eagle Pride Club took to social media to voice their frustrations.

Their statement reads:

This kicked off a digital back-and-forth between Eagle Pride Club and Armstrong Ash, who used her university-affiliated Instagram account to comment on the post, bringing up her visit to Pride Center and stating that she heard actionable feedback she believed executive leadership at Eastern would embrace.

“I have more individual conversations this week and next. I also welcome additional students reaching out,” Armstrong Ash wrote in a response on Instagram. “Once I can put things together, I have offered to share the tangible takeaways we will be moving forward on. While I have ideas based on what I have already heard, I want to make sure it is representative of what students have shared.”

Swenson and the other members of Eagle Pride were frustrated with Armstrong Ash’s response — which they found insensitive and untimely — and the lack of any response at all from McMahan.

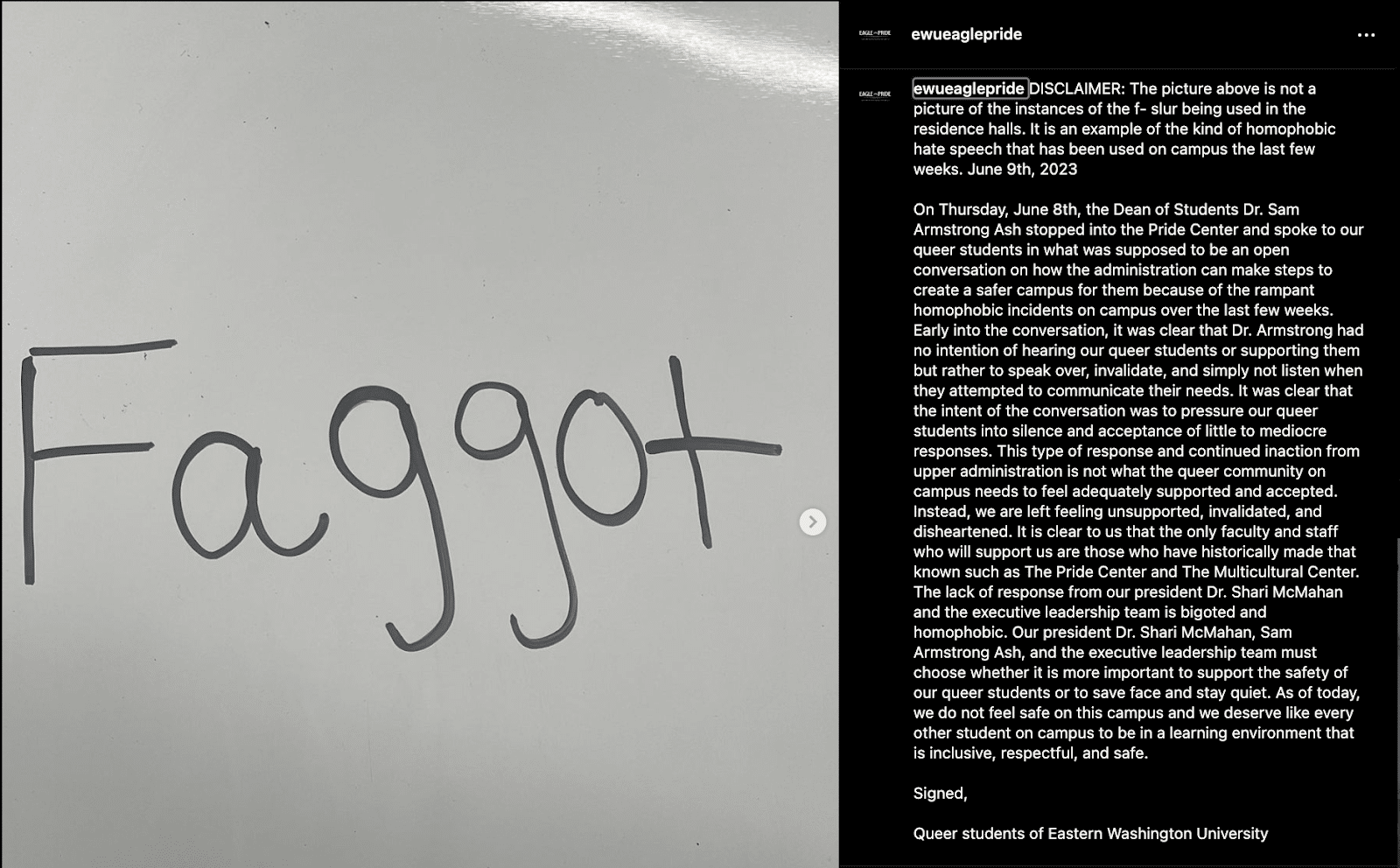

Eagle Pride responded on Instagram with a second statement two days after the first, accompanied with an image of a slur written in dry erase marker — an illustration of the kind of language queer students in residence halls had been subjected to for weeks with no official response from the university.

Armstrong Ash responded to the post in two comments, the first reading, in part: “I recognize that intent and impact did not align and want to acknowledge the additional pain and frustration I caused. I am hopeful that, as we move forward, our LGBTQIA+ community will see values in action and increased support.” She also posted a video to her account, apologizing for the impact of her words, stating that her goal as a professional is “to do everything that I can to create a more inclusive, respectful, and supportive learning environment for our students,” and asking students to engage with her in this work by sending her DMs or emails.

For some students, her message was more posturing than actual partnership.

A document sent in mid-June to administration that was penned by the Eagle Pride, BSU, QTPOC and Queers in STEM club leadership was shared with RANGE. In the document, titled Reflections from Queer Students about EWU’s Executive Administration, students wrote of Armstrong Ash: “Both times she stopped by the Pride Center last week, it was to speak with staff about the politically correct way to respond to our statements, not to the students who made them, who happened to be present during her visits. When she did open dialogue with students it was to talk over them and deflect responsibility from the Executive Administration.”

Swenson said Armstrong Ash lacked sensitivity, openness and follow-through, pointing to Armstrong Ash failing to meet with Eagle Pride after saying she wanted to and posting a photo with a student who was targeted with the slurs with a caption that she would be working with him to improve inclusivity.

Max was more generous toward Armstrong Ash’s response and engagement, saying that, although other students felt minimized and unheard by Armstrong, they believe Armstrong Ash acknowledged her mistake and continues to advocate for diversity on campus.

The social media back and forth wasn’t the only source of frustration as the spring quarter came to an end. On June 15, Eagle Pride officers found out secondhand that the president wanted to meet with impacted students, but it was scheduled for the next day at 1 pm,which was the last day of the quarter when many of the students were in finals or packing up to move out. With the poor timing and short notice, Swenson nor any of her friends were able to go to the meeting.

“I really feel like the day that the president decided to meet with us was very intentional so that hardly anyone could show up,” Swenson said. “The fact that there was no official response from her was a slap to the face.”

Max said that they were chosen by the president to participate in this meeting, and left feeling more optimistic for the future. They were appreciative that the administration took the time to meet, and signed up for the Student Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Advisory Council that was discussed at the meeting.

The council, according to Meany, is made up of 17 students selected by the administration and who represent a variety of backgrounds, majors and identities, and will begin meeting with the Office for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, the ASEWU Diversity Outreach Officer, and a representative of Student Affairs in October. He said the goal of the council is for students to bring concerns and insight to administration about how to best serve students from different identities and backgrounds.

Despite being active in advocacy on campus, a student employee, and in club leadership, Swenson was not invited to join the council. She thinks the formation of the council is a step in the right direction, but worries that the administration will choose students who are “easily manipulated” or not actually involved in activism.

“I hope they choose students that are passionate and loud-spoken,” Swenson said. “Because that’s what we need on a board like that.”

When asked why the president didn’t make a public statement in response to the homophobic incidents happening on campus, Meany said “Eastern Washington University prides itself on being supportive of all students and is not homophobic.”

“Dr. McMahan’s remarks during graduation ceremonies focused on unity, and the president distributed multiple messages during spring quarter emphasizing her commitment to diversity and inclusion, while denouncing any type of hate or intolerance,” Meany said. “In response to a student impacted by a slur in the residence hall, the university took immediate action, and the incident went through the student conduct process.”

Meany also stated that Eastern is beginning a new university-wide strategic process this month that aims to integrate diversity, equity, inclusion and justice principles based on feedback from DEIJ leaders and representatives.

Dr. Pui-Yan Lam, a professor at Eastern for over 20 years and the current president of the faculty organization, hopes that looking into the next academic year, students will find solace and support from the faculty. Lam said that she and her colleagues in faculty leadership are determined to make an impact on increasing equity and inclusivity for students, and have spent time this summer championing the idea of cultural humility — a term they use in place of “cultural competency” to mean approaching equity work from a place of curiosity and humility rather than confidence and intellectual knowledge. This has manifested in faculty development work and shaping committees with a lens bent toward equity.

“We are listening. We are trying our best, and we do want to make changes so that we can serve our students better,” Lam said, speaking on behalf of herself and her colleagues in the faculty organization. “We will continue to work with university administrations to push for the institutional changes that need to happen. Our systems in place within the university, our practices, our policies — there’s a lot of work that needs to be done collectively for the university.”

A president’s actions speak louder than words

For both Swenson at the Pride Center and Alexander in the Multicultural Center and BSU, President McMahan was a source of frustration. They described parallel experiences with administration and the president that included a lot of listening, and if there was learning, it didn’t lead to much action.

“I really just saw a lot of the equity gaps and diversity gaps that the university had and that were continually being brought up to them via me as a student, a staff member, and a Black woman and president of BSU,” said Alexander. “Multiple other students — our Native American students, our queer students — were continually telling the university, the president specifically, and her cabinet, what was going on and what their marginalized students were going through, and they just kind of ignored us.”

From a first meeting with the president that Swenson described as “passive-aggressive,” her experience with McMahan has been disappointing. She cited a pattern of lack of attendance at important Pride Center and Multicultural Center events, a tendency to prioritize image over actions, and a lack of genuine care for queer students.

“As a student, you hope your university president would care or other faculty members like our dean of students would care and show up for us,” Swenson said. “But that's not what's happening and it's very less than ideal. We’ve been met with a lot of no action or fake advocacy and that’s not what we want.”

Meany said, “Dr. McMahan's dedication to supporting students and promoting an inclusive environment remains unwavering.” He also noted that McMahan attended the LGTBQ+ alumni reception at Drag on Ice earlier in the year, sent vice presidents to attend Lavender Graduation, the annual ceremony to honor graduating queer students, in her stead, and represented Eastern in Spokane’s Pride Parade, walking alongside students and staff.

The queer leaders who penned the Reflections document believe that McMahan’s actions speak for themselves, saying that the president tends to show up for events in the last 20 minutes, avoids engaging with students at the events and is known for misgendering her staff without apology.

“How much strife will it take for the administration to put their money where their mouth is when it comes to diversity and inclusion? How much blood will the administration require before the administration deems us worthy of support? Actions speak louder than words, and the present actions say, ‘We do not meaningfully care about you,’” they wrote.

Because of the seriousness of the claims made by student leaders, RANGE gave Armstrong Ash and McMahan multiple opportunities to comment. Meany replied: "Eastern stands by the responses provided earlier this week, and the president and the dean stand by their unwavering commitment to supporting LGBTQ+ students at Eastern and hearing out any concerns they may have.”

When asked about McMahan’s “unwavering commitment,” Swenson took a pause, weighing her words carefully.

“I feel like she commits a lot to being a fake advocate. And I know that’s harsh language to use, but not only do I feel that way, but a lot of students that I've talked to about President McMahan have felt [that way].”

‘What will we do without Vanessa?’

For all the issues student leaders brought to RANGE, regarding university response to hate events, they say Delgado was the opposite. Roy, Swenson and Alexander each described her as a fierce, tireless advocate for marginalized students.

Swenson said Delgado helped her and other students navigate the complicated reporting process for bias incidents, and followed all administrative channels to support them. But Swenson made a point to say that Delgado also set clear boundaries about what she could and could not be supportive of. “Vanessa was always like, ‘I can't really get super involved in how you guys respond because I don't want it to affect my job.’”

Roy, who works in the Multicultural Center, confirmed that while both clubs frequently hung out in the Multicultural Center and Pride Centers, no employees were connected to the social media posts made by the student clubs.

Roy describes Delgado as someone who really cared for students and worked hard to create spaces that felt like home for them. Student descriptions of Delgado — whose Linkedin profile shows a decade-long career supporting queer and BIPOC students in higher education — paint her as a staunch supporter of students and a dedicated creator of safe spaces on campus.

These descriptions are in stark contrast to complaints from students about McMahan and Armstrong Ash. Yet, it’s Delgado who won’t be returning to campus this fall.

As Swenson prepares for her junior year, she has mixed feelings. While she still feels safe in the Pride Center, and identified other queer staff members who make her feel supported, she is nervous about returning to campus. Delgado’s termination leaves queer and BIPOC students down a fierce advocate, and leaves staff members walking a delicate tightrope of supporting students while staying on the administration’s good side.

“If you would've asked me in April, I would've been like, ‘Yeah, I feel super supported on campus. I feel very included. I don't have any issues with my queer identity. I never feel like I would be targeted,’” Swenson said. “Going into this year, my mindset has definitely changed a little bit just because I know now if something really serious happens on campus, administration won't do anything.”

When Swenson, Roy and Alexander describe Delgado, the same words keep coming up: advocate, supportive, safe. Delgado was the person they trusted to help hold administration accountable to the needs of their queer and BIPOC students. Roy said she helped students feel like Eastern was their home.

Meany said that two employees have been promoted to lead the Multicultural and Pride Centers, respectively, as associate directors. In addition to being director of both the Pride and Multicultural Centers, Delgado also held the title Director of Student Equity and Inclusion Services. RANGE was not provided with a replacement plan from the university for that role.

Neither Alexander nor Swenson think any of the university’s promises could balance out Delgado’s termination.

“It's really confusing and baffling to hear from the administration at Eastern, Oh, we care about diversity, we care about discrimination, we care about racism and homophobia,” Alexander said, “and then the one person that all of your marginalized students tell you this person has our backs, we feel supported by them,’ that’s the first person you terminate.”

Swenson is planning to return to work at the Pride Center, and is dreading coming face-to-face with the Delgado-sized hole at its heart. Because Delgado’s termination occurred over the summer break, her absence will be a surprise for many students. “I think a lot of students are going to come in looking for Vanessa, and Vanessa just isn't gonna be there,” Swenson said.

Roy doesn’t think Swenson’s fears are unfounded.

“A lot of our students are at Eastern because of Vanessa and a lot of students who would have dropped out didn’t because of the support of Vanessa, so we’re a little worried too about how the changes will be received,” Roy said. “But the staff at the Multicultural and Pride Centers remain here to support students.”

The fear associated with Delgado’s absence is two-fold for Swenson: as vice president of Eagle Pride, she is nervous that the public statement she helped pen is to blame for Delgado’s departure. “Vanessa, Maggie, and Naite [Harty and Boham, current staff members in the Pride Center] work tirelessly but should not fear for their jobs when pushing for increased resources,” the queer student leaders wrote in their Reflections.

Now, that quote could stand as a warning: Vanessa was a relentless advocate for queer students and students of color, and look what happened to her.

“I don't know if any of our role in taking a stance on the homophobic things was a part of why Vanessa got fired and it makes me worried, if we do another Instagram post, will that put Maggie and Naite in jeopardy of also losing their jobs?” Swenson asked, with a quiver in her voice.

Though Alexander’s time at Eastern is concluded, she shared Swenson's concern that leadership at the university is targeting employees who advocate for marginalized students.

“It's just very tricky because they're very clearly firing people … who stand up for discriminated-against students, marginalized students, students of color, Black students, queer students, our indigenous students or Latinx students,” Alexander said. “And it just feels like it's very retaliatory. It's disheartening because what happens when all the safe people at the university are gone, but you're still trying to tell us that you care?”

Despite her fears, Swenson is determined to continue to fight to make campus a safer place, and hopes that more students will be motivated by the university’s lack of response to redouble their efforts.

“It's clear that our university wants to silence minorities on campus, and that's not gonna silence us,” Swenson said. “That's just gonna make us louder.”

Correction: A previous version of this story said Delgado started Eagle FAM. The program was actually started by former EWU staff member Shantell Jackson, but has been administered by Delgado in recent years.