Editor’s note: The article discusses sexual assault. “Guarded by Predators” is a new investigative series exposing rape and abuse by Idaho’s prison guards and the system that shields them. Find the entire series at investigatewest.org/guarded-by-predators.

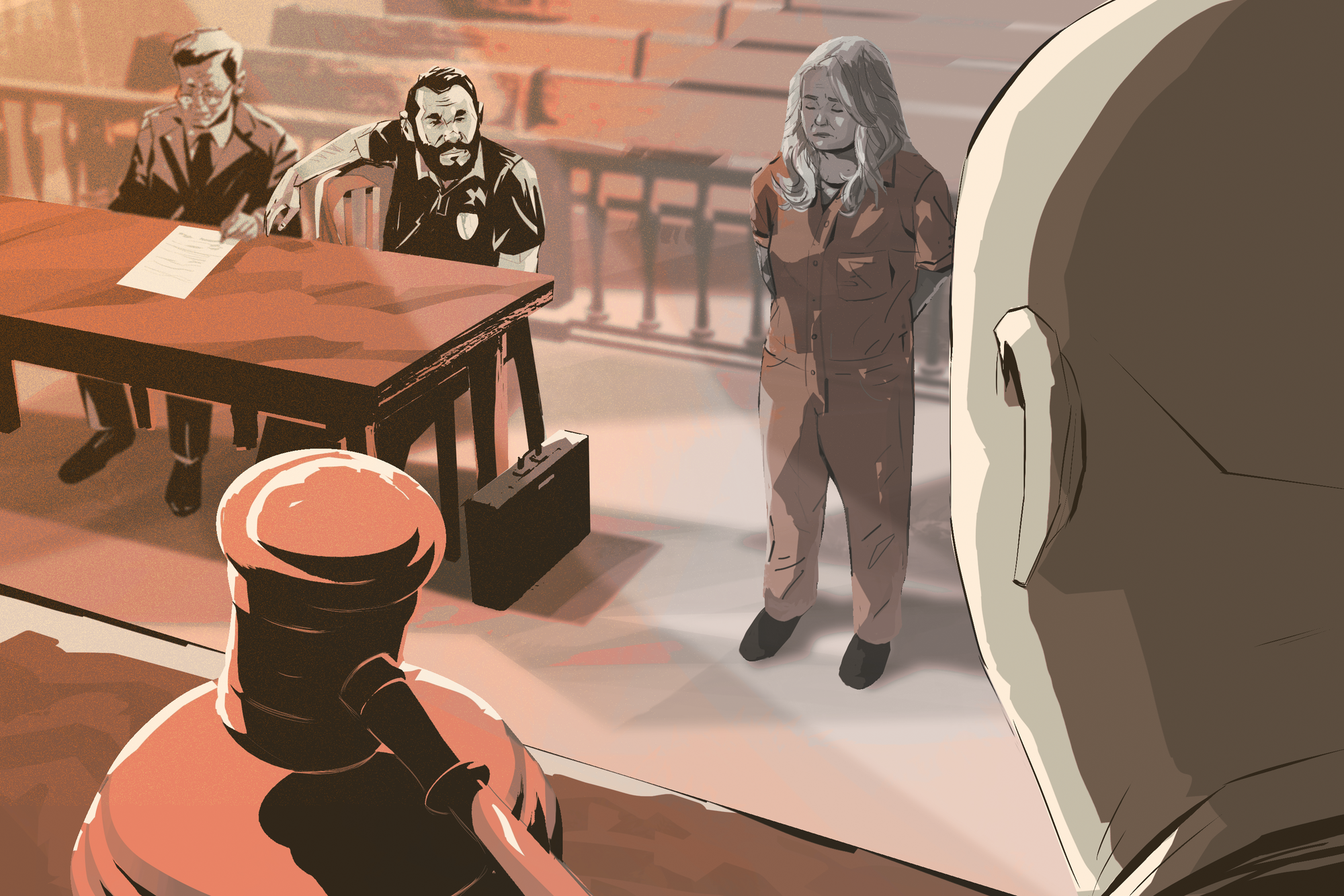

In a small courthouse in southeast Idaho, a woman incarcerated at the nearby prison had just finished testifying that a male guard came into the bathroom on her cellblock and kissed her on at least five different occasions.

She also told the court that one day, around Easter in 2012, the guard, Kim Rogers, had followed her into a janitor’s closet at Pocatello Women’s Correctional Center, reached under her shirt and grabbed her breasts. A week later, in the same closet, Rogers put his hand down her panties and touched her before she yanked his arm away, she testified.

That may have been a crime according to Idaho state law, which deems genital contact between prison staff and a prisoner — but not groping or kissing — illegal. Rogers had even confessed to a detective that he touched her “vagina.” But his defense attorney still argued that it was not necessarily an admission to a crime.

Rogers’ attorney, Justin Oleson, challenged the detective who took the stand next, asking why he didn’t ensure Rogers understood the word “vagina.”

“I assumed that due to his age and experience, and the fact that he was in law enforcement and had training with proper contact with inmates, and what he should and should not do, that that had already been covered during that training,” Detective Tony Busch replied.

For the next five minutes, the woman listened as four men — a prosecutor, defense attorney, judge and police detective — debated what, exactly, Rogers meant by vagina.

“Where did he touch her vagina at?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t ask. Anywhere is a violation of the law, whether it’s the front, back, side, it doesn’t matter.”

“Did you ask him how he knew that he touched her vagina and not just her pubic hair?”

“I don’t recall if I asked him that or not.”

“Do you think he…”

“He understood what I was asking, yes.”

“And you know that because he defined those areas for you?”

“No, he looked at the ground, put his head down and said, ‘I know what I did was wrong. I made a mistake.’”

Oleson, the defense attorney, eventually arrived at his point.

“As I think somebody told me when I was a little kid, boys have outies and girls have innies,” Oleson said. “So, it’s pretty easy to determine whether you’ve touched a male’s genitals. He touched, according to the officer, her vagina, but what does that mean? I believe the state has a burden to prove what the genitals are. They haven’t.”

Judge Paul Laggis, exasperated with the defense’s argument, conceded that Idaho state law does not clearly define a woman’s genitals. Bannock County prosecutor Vic Pearson later offered Rogers a plea deal for a lesser charge of attempted sexual contact and a penalty of eight years’ probation. Rogers accepted it. He served no prison time for the abuse. His probation was dismissed after serving less than five years and the charge was removed from his record.

The case against Rogers highlights how difficult it can be for prosecutors to hold correction officers accountable for sexual abuse, even when a guard seemingly confesses to the crime.

Idaho, like many states, limits its definition of sexual assault when the victim is an inmate. Even though federal standards say all inappropriate touching by prison workers and even suggestive comments or voyeurism are illegal, Idaho’s law protects inmates from abuse only when staff touch the victim’s genitals or they’re made to touch the genitals of staff.

The exterior of the Ada County Courthouse in Boise, Idaho. (Kyle Green/InvestigateWest)

It’s still illegal in Idaho to touch the groin, inner thighs, buttocks, breasts or genital area of any person, including an inmate, without their consent. Guards can be charged with felony or misdemeanor sexual battery for abusing an inmate. But that rarely happens.

Incarcerated victims often go along or reluctantly agree to sexual requests from guards because they’re afraid of what will happen if they say no. For that reason, inmates cannot consent under federal and state laws written specifically to protect prisoners from abusive workers, requiring only proof that the sexual contact occurred. Idaho’s sexual battery laws, however, don’t recognize the power that prison staff hold over the people in their custody and, therefore, require prosecutors to prove that the victim did not consent. Prosecutors say that is especially challenging when the victim is an inmate, who is often perceived as untrustworthy.

The result: Idaho guards harass and assault inmates with impunity and little fear of criminal consequences. In the rare cases that they are charged, accused guards are typically offered a plea deal that requires no prison time, while their victims spend years incarcerated for drug offenses, DUIs and parole violations.

InvestigateWest interviewed dozens of women who described, in detail, sexual harassment and assaults they experienced from prison workers. But few of their abusers were ever charged with any crimes.

In the last decade, 11 Idaho prison staff at men’s and women’s facilities have been prosecuted for sexually assaulting an inmate. Only two were sentenced to a prison term — but instead of serving their yearslong sentences, they served fewer than 10 months in a treatment program where participants are housed separately from the general prison population.

Prosecutors and investigators are trained to be skeptical of people in custody, longtime federal prosecutor Fara Gold acknowledged in a 2018 report to federal prosecutors. And inmates who struggle with addiction or have lengthy criminal histories are even less likely to be believed, according to the report, which offered guidance on prosecuting law enforcement sexual misconduct. And that’s likely why their abusers choose them, she said.

“The challenge in prosecuting any sort of law enforcement misconduct, but certainly law enforcement sexual misconduct, whether it’s police officers or jailers, is that they choose victims who no one is going to believe,” Gold said. “They are targeted, these victims, because the perpetrators bank on the fact that no one’s going to believe them.”

Attorney Joseph Filicetti, shown here outside his office in Boise, Idaho, authored and lobbied for the Idaho state law that criminalizes sexual contact between corrections staff and prisoners. But even Filicetti says the law, which only protects inmates from assaults that involve contact with a person’s genitals or anus, doesn’t do enough to protect people in custody. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Filicetti)

Control and consent

Idaho made it a felony for corrections officers to have sexual contact with inmates in 1993, long before the U.S. Department of Justice developed its standards.

The law, written by a former Ada County deputy prosecutor, carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment but lacks a mandatory minimum sentence, leaving penalties up to a judge. That allows most offenders to avoid prison time altogether.

Meanwhile, Idaho incarcerates more women per capita than any other state, driven largely by harsh drug charges, many of which have mandatory minimum sentences. Early this year, state lawmakers imposed a fine of at least $300 for possession of up to 3 ounces of marijuana. Quantities over 1 pound carry minimum sentences of at least one year in prison and a $5,000 fine. And last year, lawmakers sharpened penalties for fentanyl users and distributors by adding mandatory minimum prison sentences.